I recently met a friend in front of the church in Piazza Sant’ Ambrogio, near Santa Croce, in a spot that is the terminus for 3 streets : via de’ Pilastri, via di Mezzo, and Borgo la Croce e via Carducci.

While waiting, I noticed for the first time, although I’ve been in this piazza a hundred times before, something new.

Looking a bit higher than I normally do, I saw a glazed terra-cotta tabernacle, in the style of the Della Robbia, of a figure that I assumed was a priest or even a pope, making a sign of blessing.

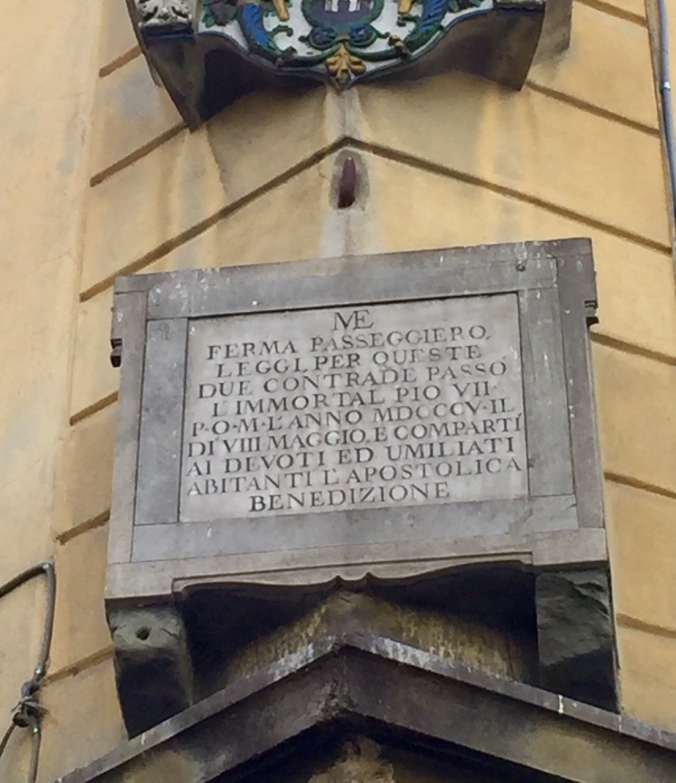

I ventured nearer to photograph the inscription below, and was rewarded with this information:

Loosely translated, the inscription reads: “Stop, you passers by, and read this. Know that 2 neighborhoods were passed by the immortal Pope Pius VII on 8 May, 1807, where he devotedly and humbly gave an apostolic blessing to the inhabitants.”

I seldom have occasion to discuss the Catholic Church, that foundational stone of Italian culture, in my blog, so let’s do a little something about that now.

Who was Pope Pius VII?

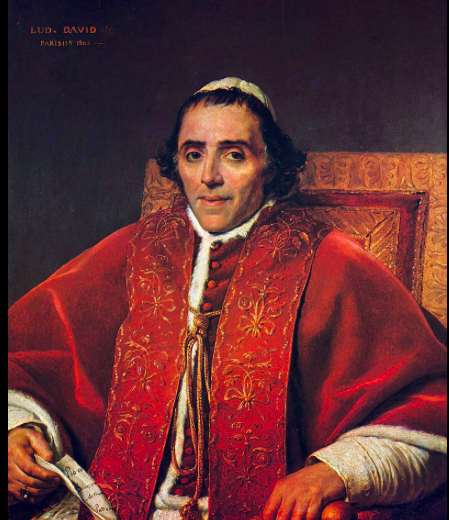

Portrait of Pius VII painted by Jacques-Louis David

He was born in 1742 as Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti. He would rise all the way to head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1800 until his death in 1823. Chiaramonti was also a monk of the Order of Saint Benedict in addition to being a well-known theologian and bishop throughout his life.

Chiaramonti was born in Cesena, about 30 miles south of Ravenna, in 1742, the youngest son of Count Scipione Chiaramonti (1698 – 1750) and Giovanna Coronata (d. 1777). His mother was the daughter of the Marquess Ghini; though his family was of noble status, they were not wealthy.

Like his brothers, he attended the Collegio dei Nobili in Ravenna but decided to join the Order of Saint Benedict at the age of 14 on 2 October 1756 as a novice at the Abbey of Santa Maria del Monte in Cesena. In 1758, he became a professed member and assumed the name of Gregorio. He taught at Benedictine colleges in Parma and Rome, and was ordained a priest on 21 September 1765.

In 1789, as the French Revolution took place, a series of anti-clerical governments came into power. During the French Revolutionary Wars, troops under Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Rome and took Pope Pius VI as a prisoner. He was taken as prisoner to France, where he died in 1799. The following year, after a sede vacante period lasting approximately six months, Chiaramonti was elected to the papacy, and took as his pontifical name Pius VII, in honor of his immediate predecessor.

He was crowned on 21 March 1800 in a rather unusual ceremony, wearing a papier-mâché papal tiara as the French had seized the tiaras held by the Holy See when occupying Rome and forcing Pius VI into exile. Pius VII then left for Rome, sailing on a barely seaworthy Austrian ship, the Bellona. The twelve-day voyage ended at Pesaro and he proceeded to Rome.

Pius at first attempted to take a cautious approach in dealing with Napoleon. He signed the Concordat of 1801, through which he succeeded in guaranteeing religious freedom for Catholics living in France, and presided over his coronation as Emperor of the French in 1804. Pius VII presided at the coronation of Napoleon I in 1804.

Once again, in 1809, Napoleon invaded the Papal States during the Napoleonic Wars; this earned him ex-communication. Pius VII was taken prisoner and transported to France. He remained there until Napoleon abdicated in 1813 and Pius VII returned to Rome. He was greeted warmly as a hero and defender of the faith and immediately revived the Inquisition and the Index of Condemned Books.

His works, some notable, some to be regretted:

Pius VII joined the declaration of the 1815 Congress of Vienna, represented by Cardinal Secretary of State Ercole Consalvi, and urged the suppression of the slave trade. This pertained particularly to places such as Spain and Portugal where slavery was economically important. The pope wrote a letter to King Louis XVIII of France dated 20 September 1814 and to the King John VI of Portugal in 1823 to urge the end of slavery. He condemned the slave trade and defined the sale of people as an injustice to the dignity of the human person. In his letter to the King of Portugal, he wrote: “the Pope regrets that this trade in blacks, that he believed having ceased, is still exercised in some regions and even more cruel way. He begs and begs the King of Portugal that it implement all its authority and wisdom to extirpate this unholy and abominable shame.”

Under Napoleonic rule, the Jewish Ghetto had been abolished and Jews were free to live and move where they would. Following the restoration of Papal rule, Pius VII re-instituted the confinement of Jews to the Ghetto, having the doors closed at nighttime.

Pius VII was a man of culture and attempted to reinvigorate Rome with archaeological excavations in Ostia which revealed ruins and icons from ancient times. He also had walls and other buildings rebuilt and restored the Arch of Constantine. He ordered the construction of fountains and piazzas and erected the obelisk at Monte Pincio.

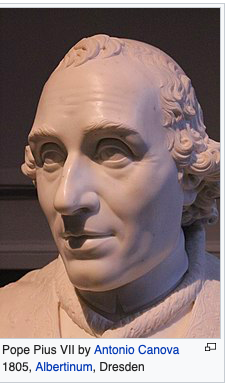

The pope also made sure Rome was a place for artists and the leading artists of the time like Antonio Canova and Peter von Cornelius. He also enriched the Vatican Library with numerous manuscripts and books.

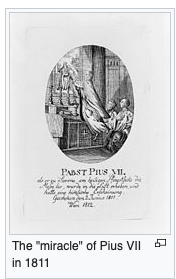

The so-called “miracle” of Pius VII. On 15 August 1811 – the Feast of the Assumption – it is recorded that the pope celebrated Mass and was said to have entered a trance and began to levitate in a manner that drew him to the altar. This particular episode aroused great wonder and awe among attendants which included the French soldiers guarding him who were in disbelief of what had occurred.

Relationship with the United States. On the United States’ undertaking of the First Barbary War to suppress the Muslim Barbary pirates along the southern Mediterranean coast, ending their kidnapping of Europeans for ransom and slavery, Pius VII declared that the United States “had done more for the cause of Christianity than the most powerful nations of Christendom have done for ages.”

For the United States, he established several new dioceses in 1808 for Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia. In 1821, he also established the dioceses of Charleston, Richmond and Cincinnati.

Pius VII died in 1823 at the age of 81. He was later buried in a monument in Saint Peter’s Basilica by the leading sculptor of the day, the Danish Bertel Thorvaldsen.