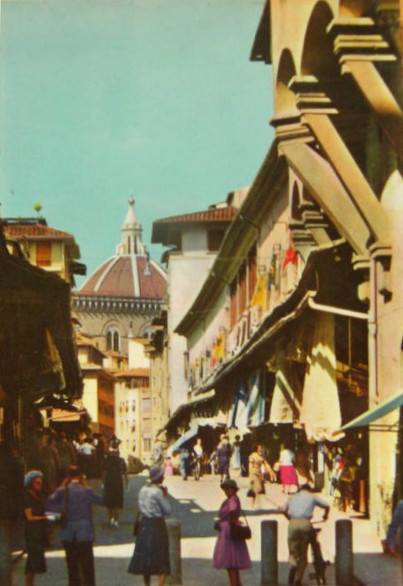

When ladies wore hats and white gloves. And I am betting the heat was just as unbearable then as now.

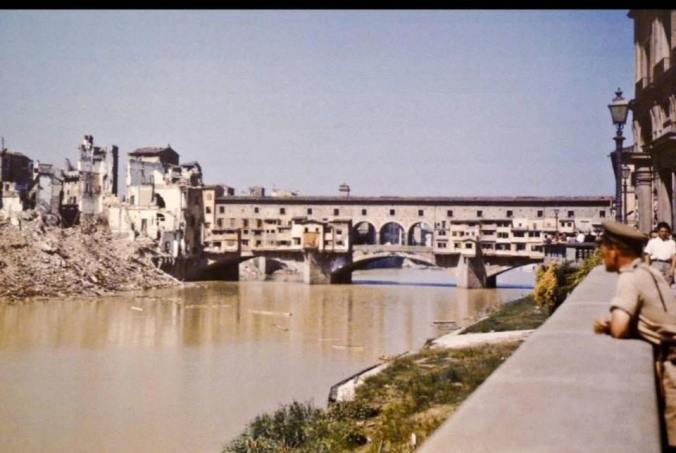

Firenze. Interno del Ponte Vecchio. Cart. Inv. nel 1966.

When ladies wore hats and white gloves. And I am betting the heat was just as unbearable then as now.

Firenze. Interno del Ponte Vecchio. Cart. Inv. nel 1966.

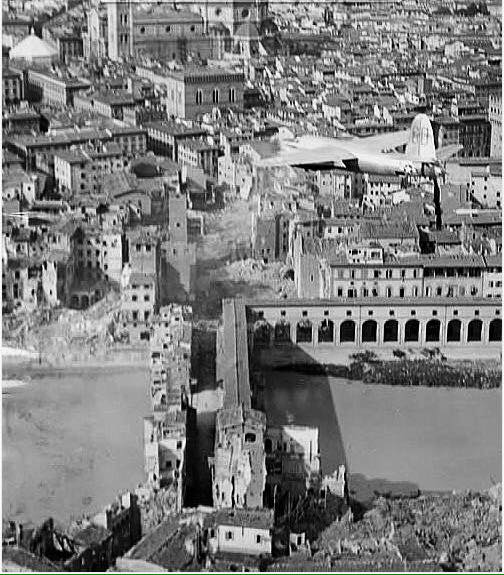

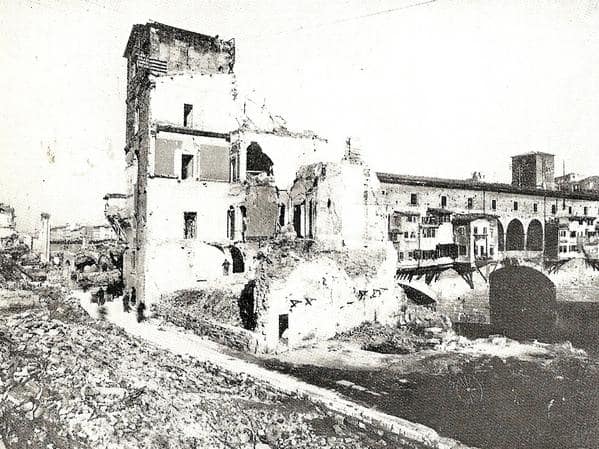

Firenze, 3 agosto 1944

All the bridges in Florence over the Arno, except for the Ponte Vecchio, were destroyed by Germans as the Allied Forces took Florence. While they didn’t destroy the Ponte Vecchio, they bombed the north and south ends of the bridge, destroying everything.

Un ufficiale Inglese osserva i danni sul Ponte Vecchio. An English officer observes the damages wrought by German forces as they were driven out of Florence.

È finita la guerra

La resa della Germania all’America, all’Inghilterra,alla Russia

Mostra il Corriere.

That was exactly my goal recently, longing to go back, even just for a couple of hours, to a simpler time when better men were President of the USA and the world seemed full of possibilities.

That’s a lot to ask of a film, but I found one when I stumbled upon It Started in Naples. Starring Clark Gable and Sophia Loren, and set in gorgeous southern Italy, what could be better?

Gable is perfect for his role in the movie and Loren is, well, Loren. Thanks to the advancement of women that has happened in the past 60 years, the silly woman Loren plays is a thing of the past. I must admit I cringed a few times with the actions and words required for her part.

I am able to overlook those weaknesses for the chance to travel, vicariously, to Naples and environs. The child actor steals the show, as does the scenery.

L’attrice Olivia de Havilland, nata il 1 luglio 1916, in Lambretta presso la loggia dei Lanzi nel 1955 circa. L’attrice nota per aver partecipato al film americano Via col Vento (Gone with the Wind).

In 1976 Brian de Palma released Obsession, which was filmed in New Orleans and Florence.

Come for the settings. Stay for the weird, melodramatic story. It’s vale la pena: well worth it.

Summertime, and the livin’ is easy…

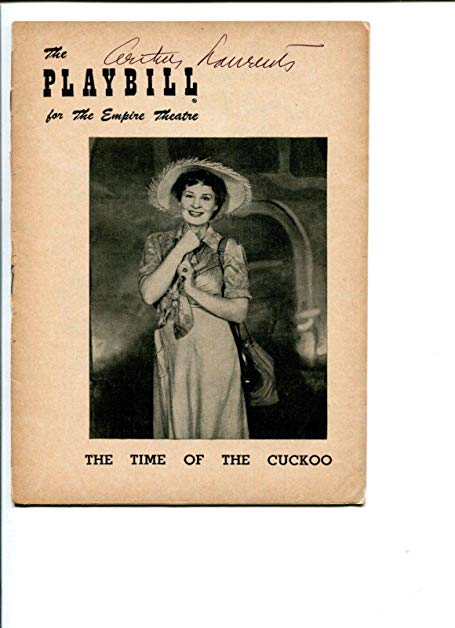

A beautiful film for a relaxing, lovely summer evening is Katharine Hepburn in Summertime. This achingly bittersweet dream of a film was directed by David Lean and released in 1955. The debonair Rossano Brazzi played Miss Hepburn’s love interest and the movie was based on the play The Time of the Cuckoo by Arthur Laurents.

Beginning with Summertime, Lean began to make internationally co-produced films financed by the big Hollywood studios.

Interestingly, Arthur Laurents had written The Time of the Cuckoo specifically for Shirley Booth, who starred in the 1952 Broadway production and won the Tony Award for Best Actress for her performance.

Ever faithful Wikipedia tells us that: Italian officials initially resisted director David Lean’s request to allow his crew to film on location during the summer months, the height of the tourist season. The local gondolieri, fearful they would lose income, threatened to strike if he was given permission to do so.

The problem was resolved when the American production company, United Artists, made a generous donation to the fund for the restoration of St. Mark’s Basilica. Lean also had to agree to a Catholic cardinal that no short dresses or bare arms would be seen in and around the city’s holy sites.

In one scene, Miss Hepburn’s character, Jane Hudson, falls into a canal when she steps backward while photographing Di Rossi’s shop in Campo San Barnaba.

Hepburn was concerned about her health and didn’t want to be in the Venetian waters. Lean persuaded her to do it anyway because he felt it would be obvious if there was a stunt double.

Lean poured a lot of disinfectant into this spot on the canal, but that caused the water to foam, which only added to Hepburn’s reluctance. The coup de grace was that he needed to film the scene 4 times until he was satisfied with the results. That night, Hepburn’s eyes began to itch and tear. She eventually was diagnosed with a rare form of conjunctivitis that plagued her for the remainder of her life.

Don’t forget it was the 1950s in a conservative world. Upon seeing the completed film, the Production Code Administration head, Geoffrey Shurlock, notified United Artists that the film would not be approved, because of the theme of adultery. Of particular concern was the scene in which Jane and Renato consummate their relationship. Eighteen feet of footage was deleted, and the PCA granted its approval.

The National Catholic Legion of Decency, however, objected to a line of dialogue that was later trimmed, and the organization bestowed the film with a B rating, designating the film “morally objectionable in part.”

In later years, Lean described the film as his favourite. He became so enamoured with Venice during filming he made it his second home.

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times observed that:

“The challenge of making Venice the moving force in propelling the script has been met by Mr. Lean, as the director with magnificent feeling and skill…through the lens of his color camera, [captures] the wondrous city of spectacles and moods. It becomes a rich and exciting organism that fairly takes command of the screen. And the curious hypnotic fascination of that labyrinthine place beside the sea is brilliantly conveyed to the viewer as the impulse for the character’s passing moods…It is Venice itself that gives the flavor and the emotional stimulation to this film.”

The film was successful: It was nominated for the BAFTA Award for the Best Film; David Lean won the New York Film Critics Award for Best Director and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director. Hepburn was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress and was also was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actress.

Farmacia della delegazione inglese aperta in via Tornabuoni nella prima meta’ dell’ ottocento da H. Roberts e C.

A couple of weekends ago, I had the pleasure of visiting a famous villa in Fiesole, the Villa Saliviati.

Of course the villa has its own (gorgeous) chapel; here is a detail of the ceiling:

And the villa also has a grotto:

There is a lot of interesting interior detailing:

In the 14th century, the castle of the Montegonzi was built on this property land already belonged to the Del Palagio. In 1445, Arcangelo Montegonzi sold it to Alamanno Salviati , the man who introduced the cultivation of salamanna and jasmine grapesin Tuscany.

Alamanno commissioned Mielcozzian workers to reduce the castle to a villa, with a garden and woods . In 1490, the nephews of Alamanno, dividing their uncle’s assets, and gave the villa to Jacopo, who was related to Lorenzo de ‘Medici.

In 1493, new, considerable renovations were undertaken, to which perhaps Giuliano da Sangallo took part and which lasted about a decade.

Giovan Francesco Rustici also took part in the works. Between 1522 and 1526 he created for the villa a series of terracotta roundels with mythological subjects (such as Apollo and Marsyas or Jupiter and Bellerophon ).

In 1529, the house was sacked by the anti-cult faction and between 1568 and 1583 Alamanno di Jacopo Salviati and his son Jacopo further enlarged and embellished the villa, with the gardens ( 1570 – 1579 ) and the buildings that border the northern border and create a scenic backdrop connected to the villa.

New Year’s eve, 1638, was an event to remember. That evening, in this villa, the severed head of the lover of Caterina Canacci, was brought to the villa, hidden under the linen that the wife of Salviati, Veronica Cybo, sent him weekly.

The villa then passed to the Aldobrandini – Borghese and on December 30th 1844 it was bought “with a closed gate” (ie with all the furnishings) from the Englishman Arturo Vansittard.

Then came the tenor Giovanni Matteo De Candia aka Mario, who lived there with his wife, the soprano Giulia Grisi , the Swedish banker Gustave Hagerman and finally, in 1901, the Turri.

During the WWII, the grotto was used as the post of an allied command: Lensi Orlandi recounted the memory of nocturnal visits of “kind and rich Florentine, often mature matrons”, who “crossed the threshold of those rooms to give honor to the admired winners” [2 ] .

There followed a long semi-abandonment, in which the villa was not accessible even to scholars (he visited Lensi-Orlandi in 1950, but could not Harold Acton in 1973 ).

In 2000 the monumental complex, together with its gardens, was purchased by the Italian Government to be destined for the European University Institute , which made it the seat of the Historical Archives of the European Union ; one can mention, among the various documents contained in them, the personal papers of the founding fathers, such as Alcide De Gasperi , Paul-Henri Spaak , Altiero Spinelli and Ernesto Rossi .

The end of the renovations took place in October 2009 and on December 17, 2009 the President of the Republic Giorgio Napolitanoinaugurated the Historical Archives of the European Union .

This villa was in communication with Villa Emilia (which was higher up) – which in ancient times was a convent of Cistercian nuns suppressed in 1453 – through an underground gallery : hence the other name with which the villa is known, “del Ponte at the Badia “.

The main body of the villa reveals its military origins, especially in the two crenellated turrets, in the corner, and in the crowning with the walkway on corbels , very similar, for example, to that of the villa of Careggi . It is made up of two adjacent buildings, but with similar architectural features: the east one is more massive and tall, the west one is of smaller volume and height.

The building is arranged around the central courtyard, portico on three sides with columns in pietra serena with Corinthian capitals ;the entablature towards the inside is decorated with graffito friezes, with the rounds of the Rustici inserted into this strip in correspondence with the round arches.

The interiors are often covered by vaulted , barrel and cross vaults .

You get to the south facing of the villa through a long cypress avenue that once led to the Via Faentina and that after the construction of the railway was modified, creating a passage on it.

The Italian garden , in front of the villa, is built on three terraces at different levels and, although it is being restored, it is made up of geometric flower beds in boxwood with flowery essences. The property is then surrounded by a large English park , where there are, among other things, a bamboo grove, two ponds and, scattered here and there, various items of furniture, such as statues, temples, caves, fountains, pavilions and more.

Villa Salviati , or villa of the Ponte alla Badia , is located along the homonymous street near via Bolognese in Florence , [1]

Palma Bucarelli was born in Rome. She earned a degree in art history at the Sapienza University of Rome.[1]

As a young art historian she worked at the Galleria Borghese and in Naples. During her thirty-three years as head of the Italian National Gallery of Modern Art, Bucarelli was responsible for protecting the gallery’s collections from damage while it was closed during World War II; she arranged to place paintings and sculptures in historic buildings including the Palazzo Farnese and Castel Sant’Angelo.[2] She was one of the Italian delegates to the First International Congress of Art Critics, held in 1948 in Paris.[3]

After the war, she oversaw such events as exhibitions of works by Pablo Picasso (1953), Piet Mondrian (1956), Jackson Pollock (1958), Mark Rothko (1962), and the Gruppo di Via Brunetti (1968). She defended controversial works such as Piero Manzoni‘s ‘”Merda d’Artista” and Alberto Burri‘s “Sacco Grande” (1954).[1] Her strong support for abstract and avant-garde works made international headlines in 1959, when she was accused of a bias against figurative art in a public debate.[4] In 1961 she was in the United States, where she gave a lecture in Sarasota, Florida[5] and attended the opening of a major exhibit on Futurism at the Detroit Institute of Arts.[6]

Palma Bucarelli married her longtime partner, journalist Paolo Monelli, in 1963. She died in Rome in 1998, from pancreatic cancer, aged 88 years. Her personal collection of art was donated to the National Gallery. Her famously elegant wardrobe was donated to the Boncompagni Ludovisi Decorative Art Museum in Rome. A street near the GNAM was renamed in her memory.[2] The Gallery mounted a show about her influence, “Palma Bucarelli: Il museo come avanguardia”, in 2009.[7]

You must be logged in to post a comment.