There’s an Italian painting at the Denver Art Museum that is one of my favorites in the world! Part of the reason it holds such a sweet spot in my heart is that when I was an undergraduate student at the University of Denver and first discovering Italian art, I chose this painting from all the works at the museum on which to write my first art history term paper. I got a nice grade for my effort and I remember the time of year (December) and subject matter (Adoration of the Magi) so well.

Here it is, in all of its Italian glory!

Adoration of the Magi, c. 1445-50

Bonifacio Bembo, Italian, 1420-1478

Born: Cremona, Italy

Active Years: 1455-1478

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bonifacio_Bembo

The Simon Guggenheim Memorial Collection

How this painting came to join the department of European and American Art before 1900 at the Denver Art Museum:

The department of European and American Art before 1900 oversees a collection that includes more than 3,000 artworks and is composed of painting, sculpture, and works on paper, with significant strengths in early Italian Renaissance, 19th century French painting, and British art from 1400 to 1900.

The Denver Art Museum began acquiring notable examples of European art as early as the 1930s, with donations from Samuel H. Kress, Mr. and Mrs. Simon Guggenheim, and the Havemeyers, to name a few. Their generosity helped initiate a collection that grew in time through gifts and purchases.

Throughout the 1950s, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim donated a significant collection of Old Master paintings, and in 1954, as one of 18 regional museums, the museum was chosen by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation to receive a gift of 33 paintings and four sculptures. Dating from the mid-1300s to mid-1600s, it was the first large collection of Old Masters to be shown in Denver. Additional gifts came from Marion G. Hendrie and the Charles Bayley, Jr. Collections.

KNOWN PROVENANCE

Chiesa di Sant’Agostino, Cremona, Italy. (Galerie Trotti, Paris), 1909. Michele Lazzaroni, Paris, by 1911, until 1926; (Alessandro Contini-Bonacossi, Florence), 1926; purchased 1926 from Contini-Bonacossi by Mr. and Mrs. Simon Guggenheim; gifted in trust 1957 by Mrs. Olga Guggenheim to the Denver Art Museum. Provenance research is on-going at the Denver Art Museum and we will post information as it becomes available.

EXHIBITION HISTORY

“Pinacoteca di Brera, Mostra dedicata ai Tarocchi Visconti Sforza”—Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, 09/23/1999 – 01/15/2000

“Arte Lombarda dai Visconti agli Sforza (Lombard Art from Visconti to Sforza) “—Palazzo Reale, 03/12/2015 – 06/28/2015

Ah, Firenze! I miss you so!

The painting is one of a pair illustrating an allegory of male naiveté and the slyness of women. “Civetta” is the Italian word for “screech-owl” but is also used informally to describe a flirtatious woman, or coquette. In the painting male birds are caught in traps set by women using an attractive woman as bait.

Personally I know from my years of living in Florence that a coquettish woman is colloquially called a Civetta in Italy. Perhaps this began as referring to flirtation with large eyes? Whatever it was, that’s the slang.

I’ve never seen a depiction of a game in which owls had men’s heads, but I remembered this 2 part sculptural group in Florence called Il Gioco della Civetta. It still doesn’t seem to be the same game being played in the painting, but until I can get back to Italy, it will remain a mystery to me.

The sculptural group of the The Owl Game (Gioco della Civetta) is located in the Boboli Gardens and consists of two white marble statues depicting two young men while playing. The aim of this game was to take the hat off to the other player who, in order to try to escape, had to bend over continuously (in Italian ‘fare civetta’). Therefore, one character is outstretched to grab the hat, while the other is attempting to deftly dodge the opponent’s move. The jacket of one of the two players is unbuttoned, precisely because of the abrupt movement that he makes by throwing himself backwards, and both figures are supported by tree stumps.

The Owl Game was originally commissioned to a sculptor known as ‘Matteo scultore’ in 1618 and its execution, which lasted for several years, was completed by different artists. The modelling was probably done by Orazio Mochi, who took inspiration from Giambologna’s Uccellatori. The statues were then sculpted by Romolo Ferrucci del Tadda, who left the group unfinished at his death, missing one figure. After various assignments, the work was finally completed by Bartolomeo Rossi in 1622. Unfortunately, The Owl Game in stone deteriorated quickly and got destroyed.

In 1775, Grand Duke Peter Leopold entrusted sculptor Giovanni Battista Capezzuoli with the task of remaking the work and the artist decided to sculpt it out of white marble instead of bigia stone. From the panel of the Giuochi rusticali (Rustic games) made by Vascellini in 1788, the group appeared to be consisting of three figures, while only two figures have survived to present days. When looking at the 18th-century replica, it is no longer possible to distinguish the hands of the various sculptors who worked on the original group in stone: Pizzorusso (1989) attributes the original of the figure on the left to Bartolomeo Rossi and the one on the right to Romolo Ferrucci del Tadda. The realisation in marble of the original group diluted the stylistic features of previous artists. The copyist was inspired by 16th-century representations of ‘peasants’, relying on the narrative and playful style that was typical of 17th-century genre painting.

At any rate, the painting is strange!

I made a new friend at the Denver Art Museum recently. This fairly recent acquisition delighted me!

This is why I love the history of art! I can time travel and see what St. Peter’s looked like around 1855. I’ve stood on the Janiculum Hill in Rome many times and gazed at St. Peter’s from this vantage point. It looks oh, so different nowadays!

Born near Edinburgh, Roberts came to be known as the “Scottish Canaletto” after the 18-century Italian cityscape painter famed for his precise representations of cities and their buildings. For over two decades Roberts traveled through Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East painting and architectural and topographical subjects. He painted this picture following a visit to Italy in 1853, the final stop of his travels before returning to London. For over a century such works had been enormously popular among British collectors as mementos of their Italian sojourns. In an inscription by Roberts he informs us that the work was a gift to the wife of his friend Joseph Arden, “…A Souvenir / of her Visit to Rome.”

Thanks to Facebook for reminding me!

These memories are one of the 1,000,000 things I am grateful for this year! Happy Thanksgiving!

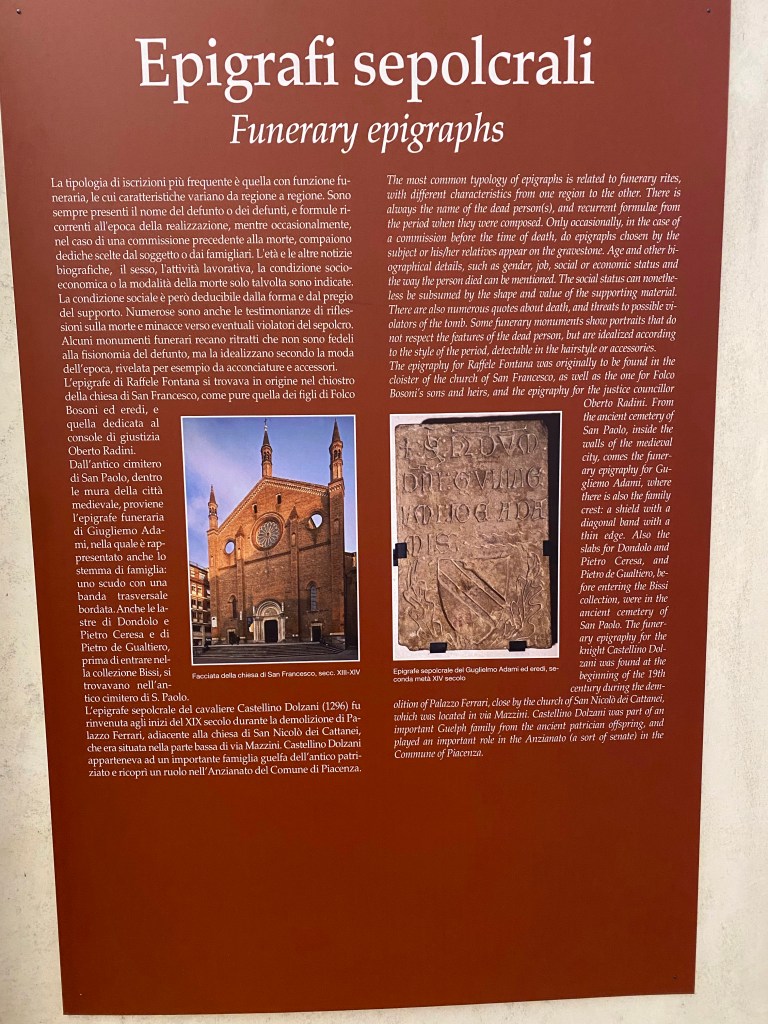

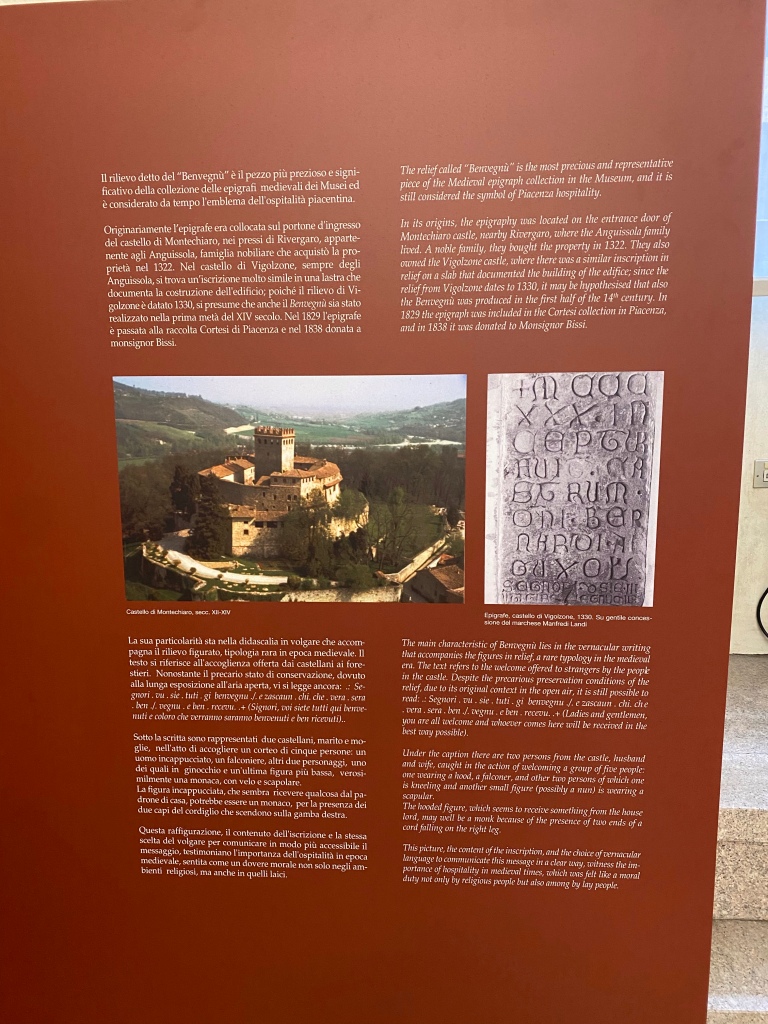

As I look back on my travel to Piacenza exactly 2 years ago, I am filled with longing to return. There is still so much left to explore. Soon, self, I promise!

Drones are a new bonus in life!

You must be logged in to post a comment.