Ah, Firenze! I miss you so!

Travel

Let’s make a quick trip to Japan!

(oh, how I wish!)

At least I can easily visit the Japanese section of the Denver Art Museum without a lot of time or expense. This museum had the good fortune of having a talented Japanese curator for decades, and he built an important collection here in Denver. I taught the subject of Japanese art history at a local university many years ago and I always love tripping to Japan in Denver, or anywhere!

These were not my best attempts at photography or videography that day. Oh well, you can’t win them all!

Piacenza masterworks, Botticelli

Piacenza, part 4, a last look

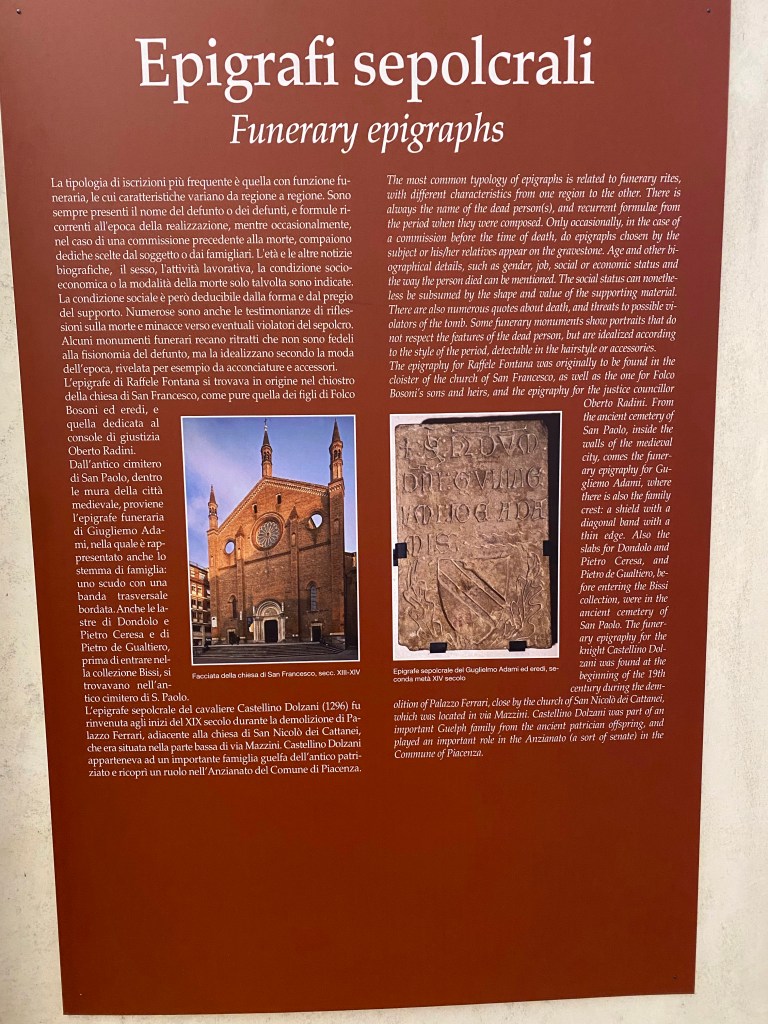

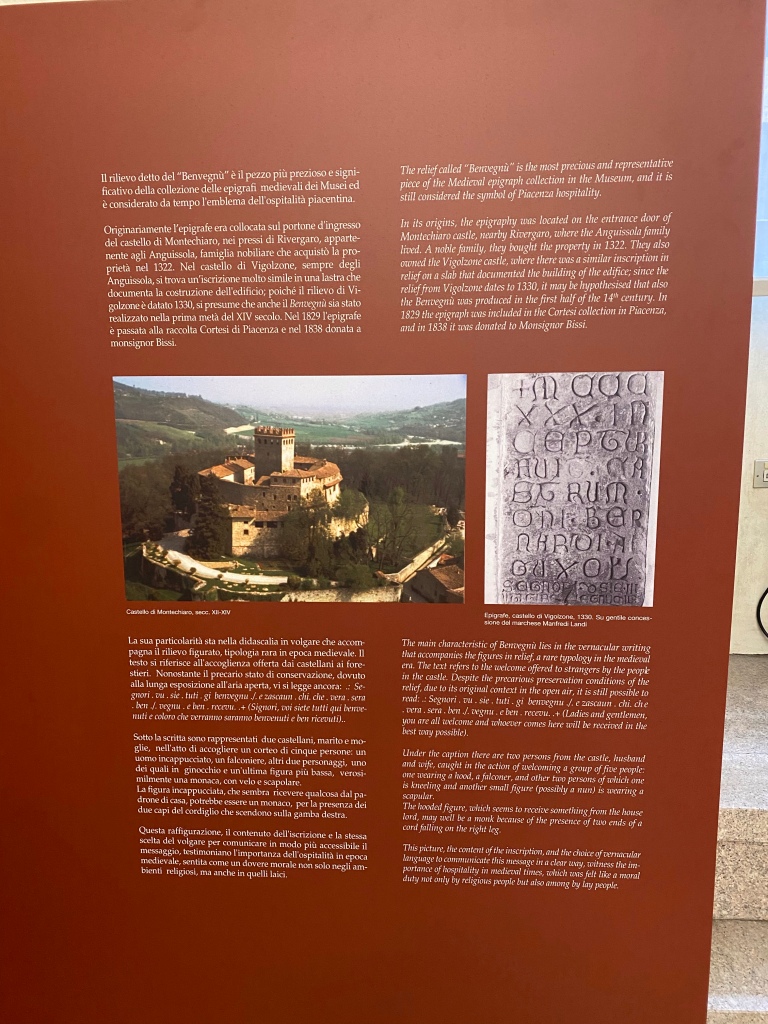

Piacenza, part 3: Palazzo Farnese

As I look back on my travel to Piacenza exactly 2 years ago, I am filled with longing to return. There is still so much left to explore. Soon, self, I promise!

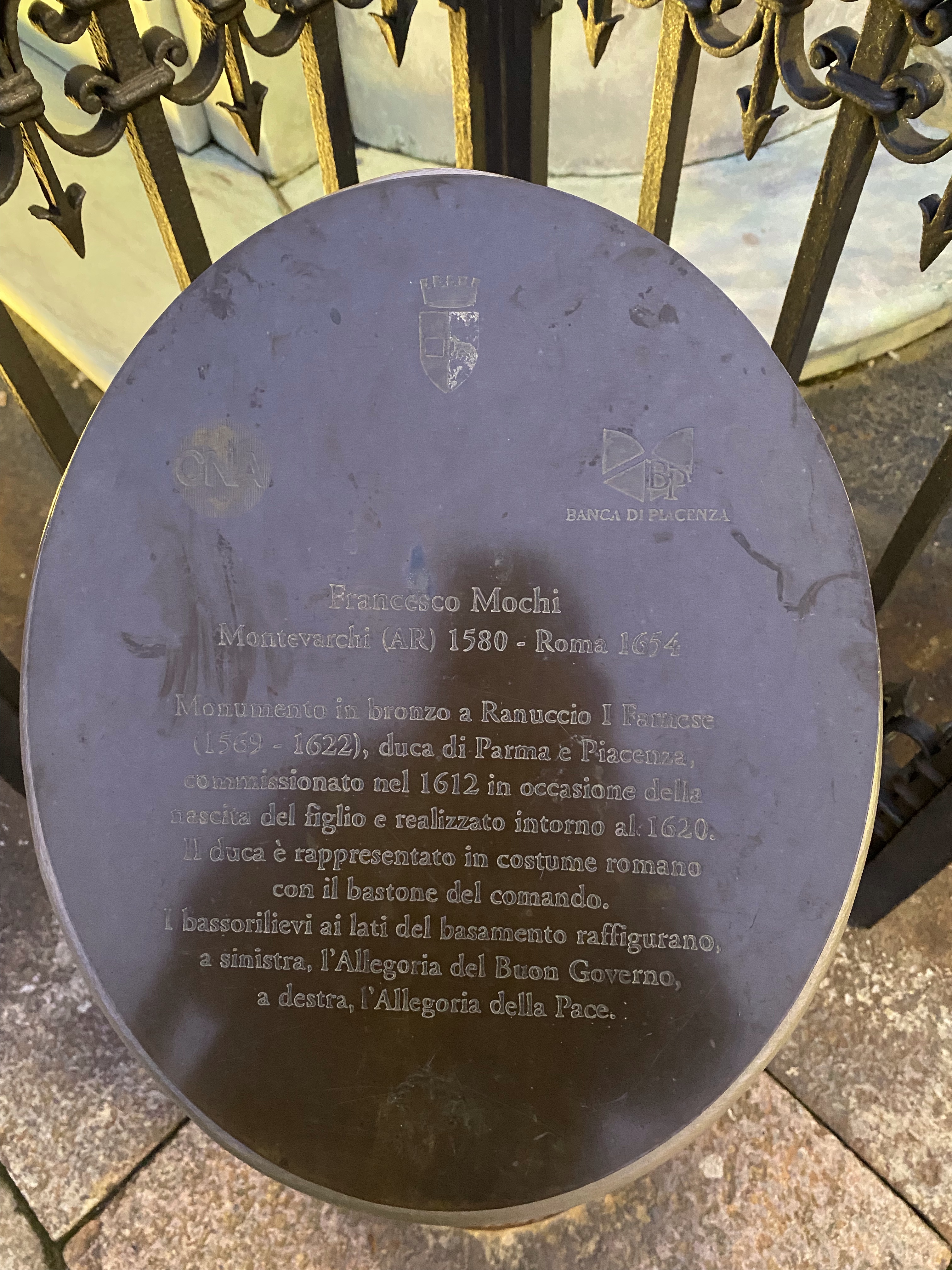

I made it to Piacenza! Day 1. Piazza dei Cavalli and the church of San Francesco

A very short two years ago (how time flies!), I had the immense pleasure of visiting Piacenza for the first time. I loved every second of my time there.

Here are some highlights from the beautiful little city. I arrived about twilight on a November afternoon, which is captured pretty well in these pictures.

The Piazza dei Cavalli is highly photogenic. The city does an excellent job with elegant lighting.

More to come, stay tuned!

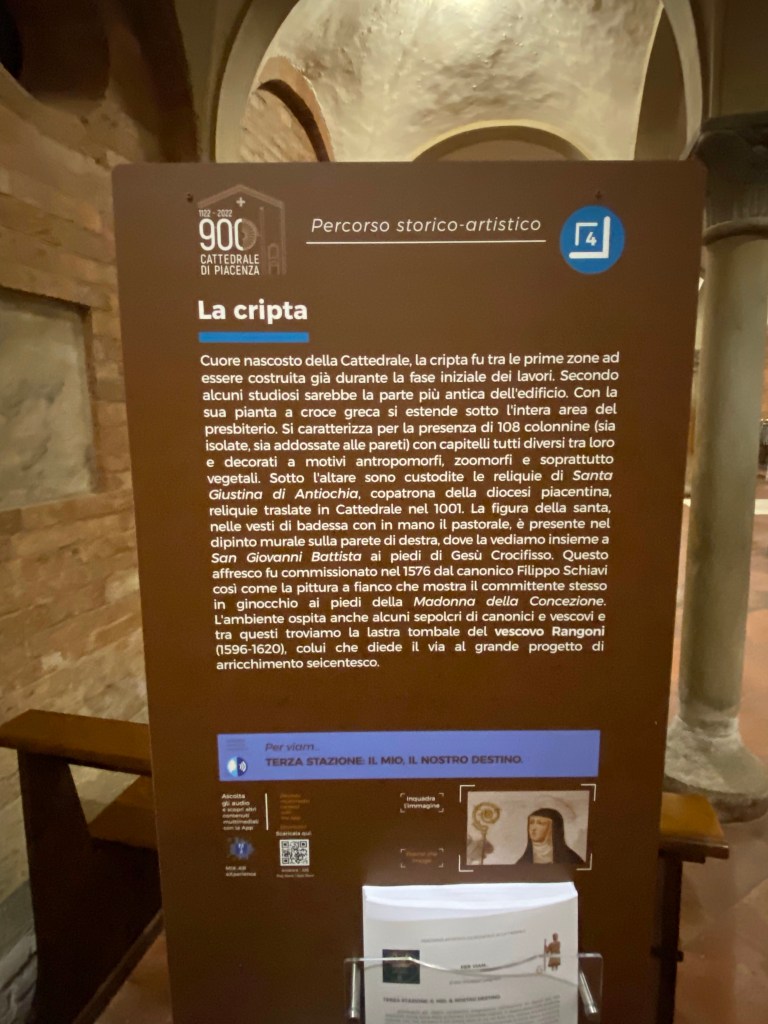

Piacenza, part 2: il Duomo

\

The look of future travel?

52 places, virtually

The miracle of flight

One minute you’re over the Appenine mountains in Tuscany…

And the next minute (well, 12 hours later, counting connections) you are over the western USA. Where it’s winter. And it’s cold. And dry.

And kind of starkly beautiful.

Check out that weird shape in the earth below, covered with snow. Alien symbols for UFOs? When I was 13, I would have thought so.

To me, the patterns and colors are beautiful.

You must be logged in to post a comment.