It will be interesting to see what follows. Will mass tourism ruin the city again?

It will be interesting to see what follows. Will mass tourism ruin the city again?

The Brenta is an Italian river that runs from Trentino to the Adriatic Sea just south of the Venetian lagoon in the Veneto region.

During the Roman era, it was called Medoacus and near Padua it divided in two branches, Medoacus Maior and Medoacus Minor. The river changed its course in the early Middle Ages, and its former bed through Padua was by then occupied by the Bacchiglione.

The 108 mile long stretch was first channelled by the Venetian Republic in the 16th century, when a canal was built from the village of Stra to the Adriatic Sea, bypassing the Venetian lagoon.

The Brenta canal made use of the system of rivers and canals that had connected the Venetian cities with each other and with the Venice lagoon since ancient times. The goods directed from the hinterland to the Serenissima Republic of Venice passed on these river routes: building materials such as wood, marble, stones from the Vicentine Hills and trachyte from the Euganean Hills as well as grains and other agricultural products. The transport took place with barges called bùrci pulled along the horse banks.

In construction the canal, the Republic of Venice imposed hydraulic changes (which several times required the engineering advise of Leonardo Da Vinci) which diverted the main river course further south, moving it away from the Venetian lagoon and leading it to flow directly into the Adriatic Sea. These hydraulic works are represented by the cuts of the Brenta Nuova and the Brenta Nuovissima, and consist of sluices and mobile bridges that have made the river navigable.

A branch of the Brenta, named Naviglio del Brenta, was left to connect directly Venice and Padova (which was a kind of second capital of the Venice Republic). The Brenta canal runs through Stra, Fiesso d’Artico, Dolo, Mira, Oriago and Malcontenta to Fusina, which is part of the comune of Venice.

With this new stretch of the Brenta connecting Venice with Padua, it came to be called the Riviera del Brenta by the 16th century. Wealthy Venetian families began to build elaborate river houses which they called villa (“villa” in the language of the time meant “country”). This was a perfect situation for these patrician families because there new homes could be easily reached from Venice with their gondolas. In fact, it has been said that with all the new building along the Canal, it was almost as if the Brenta canal was an extension of Venice’s Grand Canal.

It also became the custom of aristocratic Venetian families to spend summer holidays in their new country houses. These homes could be reached by richly decorated, luxurious wooden burchielli, or ships.

These vessels had elegant cabins, with three or four balconies. The interiors were finely decorated and adorned with mirrors, paintings and precious carvings. On the way to the lagoon they were propelled by wind or oars, while on the route from Fusina to Padua along the Brenta Riviera, they could be pulled by horses.

Cargo was carried on traditional barges known as burci.

After 1797 , with the fall of the Venetian Republic and the consequent decline of the Venetian patriciate, the burchielli fell into disuse.

Among the first villas to be built, and one of the most important, is Casa Foscari designed by Andrea Palladio at Malcontenta (located shortly after the gates of the Moransani). The illustrious Foscari family was established by the 15th century, when a Foscari was a popular doge in the Venetian Republic for 34 years.

Another Palladian villa, which was built for Senator Leonardo Mocenigo around 1560-61, was destroyed. But its very existence, along with Casa Foscari, shows how quickly patrician settlements multiplied on the shores of the Brenta Canal. In the Mocenigo Villa, the architect created a rather original design with respect to the typical pattern of Venetian villas, which he later published in the second of his Four Books of Architecture. Sadly, that villa fell into disrepair by the late 18th century and was demolished.

After the Foscari and Mocenigo ville, most new homes along the canal were not as important architecturally. They were mostly homes of modest size. But the trend for vacationing along the canal, and the taste for villa life, was well established. Homes known as barchesse contained large rooms and were almost always ornamented with decorative frescoes. Extant examples include buildings of the Villa Valmarana, the Villa Contarini Venier in Mira (currently the seat of the Regional Institute for Venetian Villas), and the Villa Foscarini Rossi in Stra.

Thus, the villeggiatura (life of the villas) understood in its original meaning, the Riviera del Brenta has become other than a residential and productive facility, a touristic infrastructure of great importance that ideally links the Euganean Hills to the Laguna, the thermal baths of Abano to the beaches of the Lido, and again, Padua toVenice.

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naviglio_del_Brenta

http://lamalcontenta.com/index.php/en/riviera-of-brenta/description

Antonio Foscari, Acque, Terre e Ville, in “Ville Venete: la Provincia di Venezia”, I.R.V.V, Marsilio, Venezia 2005, pp. XXX-XLII

Antonio Foscari, Tumult and Order, Lars Mueller Publisher Zurigo, 2011

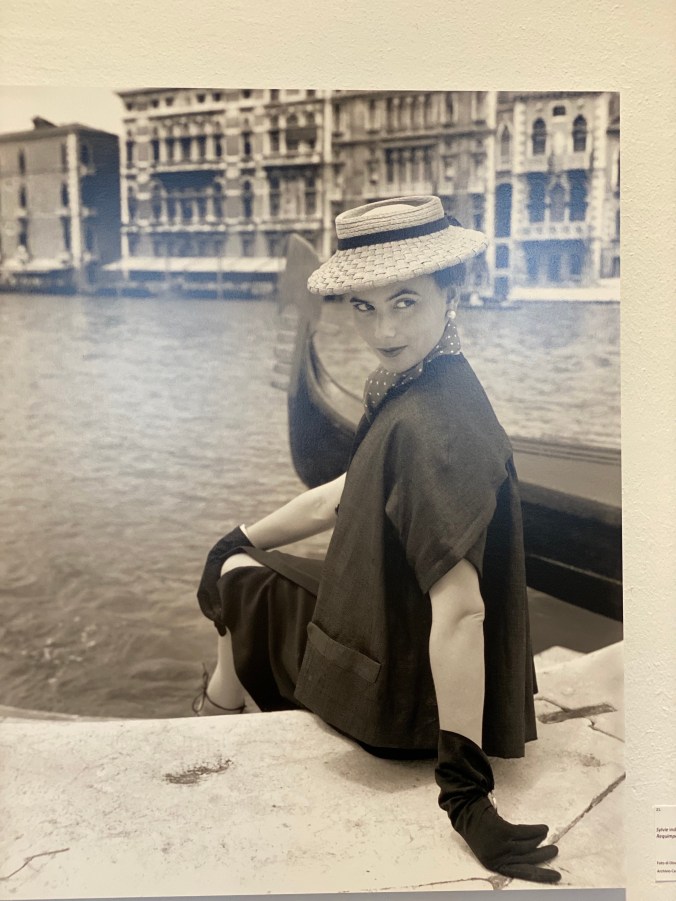

This lovely little exhibition, entitled Timeless Elegance, Dior in Venice in the Cameraphoto Archives, is currently on display at Villa Pisani, in Stra, on the Brenta Canal in the Veneto. I enjoyed seeing it very much.

From the website of the Villa:

1951 was a magical year for Venice. Some of the most intriguing views of the city co-starred in the campaign that publicised the creations of the couturier who was capturing all the world’s headlines at the time: Christian Dior.

On 3 September of that same year, Palazzo Labia hosted the “Ball of the Century”: the Bal Oriental, organised by Don Carlos de Beistegui y de Yturbe, attracted around a thousand glittering jetsetters from all five continents. This masked ball saw Dior, Dalí, a very young Cardin, Nina Ricci and others engaged as creators of costumes for the illustrious guests, in an event that made the splendour of eighteenth-century Venice reverberate around the world.

Silent witnesses of both of these events were the photographers of Cameraphoto, the photography agency founded in 1946 by Dino Jarach, who covered and recorded everything special that happened in Venice and beyond during those years.

We have Vittorio Pavan, the current conservator of the imposing Cameraphoto Archives (the historical section alone has more than 300,000 negatives on file) and Daniele Ferrara, Director of the Veneto Museums Hub, to thank for the project to show the photographs of those two historical events to the general public. The location chosen for them to re-emerge into the light of day is one of extraordinary significance: Villa Nazionale Pisani in Stra is the Queen of the Villas of the Veneto and it is no coincidence that it is adorned with marvellous frescoes by Giambattista Tiepolo, the same artist whose work also gazed down on the unforgettable masked ball in 1951 from the ceilings of Palazzo Labia.

For this exhibition, Pavan has chosen 40 photographs of the collection shown in Venice by Christian Dior.

In those days, every fashion show would present just under 200 models, calculated carefully to achieve the right balance between items that would be easy to wear and others that made more of a statement. Dior was the undisputed master of fashion in those post-war years. The whole world looked forward to his collections and discussed them hotly. No fewer than 25,000 people are estimated to have crossed the Atlantic every year, just to see (and to buy) his collections. Every time he changed a line (and every new season brought such a change), it was accepted with both enthusiasm and ferocious criticism: the former from his clan of admirers, the latter from those who opposed him.

In any case, no woman who aspired to keep abreast of fashion could afford to ignore the dictates issued by the couturier from his Parisian maison in Avenue Montaigne, where he already employed a staff of more than one thousand, despite having being established only five years before. Dior’s New look evolved with every passing season.

In 1950, he introduced the Vertical Line, in 1951 – as the photographs on show in Villa Pisani illustrate – no woman could avoid wearing his Oval Look: rounded shoulders and raglan sleeves, the fabrics modelled until they clung like a second skin. The essential accessory was of course the hat, for which Dior that year drew his inspiration from the kind traditionally worn by Chinese coolies.

For that autumn, though, he created the Princess line, which gave the illusion of extending below the breast.

In the breathtaking photographs from the Cameraphoto Archives, beautiful Dior-clad models perform a virtual duet with Venice, whose canals, churches and palaces are never a mere backdrop, but co-stars on a par with the great designer’s creations.

The second nucleus of this fascinating exhibition is devoted to the Grand Ball at Palazzo Labia, possibly the most glittering social event of the century.

All the bel monde flocked to Venice on that legendary 3 September. Don Carlos, popularly known as the Count of Monte Cristo, sent personal invitations to a thousand people. Dior, together with a veritable army of young tailors and accompanied by Dalí, was engaged to create the most alluring costumes, all designed to refer to the eighteenth century when Goldoni and Casanova lived here. There were costumes for men and women, but also for the greyhounds and other dogs that often accompanied their owners.

The torches that on that legendary evening illuminated the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, several Grandees of Spain, the Aga Khan, King Farouk of Egypt, Winston Churchill, many crowned heads, princes and princesses, a host of millionaires, such artists as Fabrizio Clerici and Leonor Fini, fashion designers of the calibre of Balenciaga and Elsa Schiapparelli and leading jetsetters Barbara Hutton, Lady Diana Cooper, Orson Welles, Daisy Fellowes, Cecil Beaton (whose photographs, published in Life magazine, gave the world something to dream about), the Polignacs and the Rothschilds.

Welcoming them in the midst of clouds of ballerinas and harlequins was the master of the house and host, who dominated the scene as he promenaded back and forth dressed as the Sun King on a 40 cm high platform. The heir of an immense fortune created in Mexico, Don Carlos spent some of his time living in Paris, where he owned a house designed by Le Corbusier and decorated by Salvador Dalí, and the rest at a chateau in the country. He had bought Palazzo Labia and restored it and was now offering it to his friends.

The aim of this exhibition is therefore to contribute to improving the appreciation and value of the Cameraphoto photography archives, which have been declared to be of exceptional cultural interest by the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, since they constitute an inestimable legacy for the wealth and variety of images.

It was with this in mind that the curators chose this nucleus of photographs depicting the clothing designed by one of the most ingenious and iconic fashion designers in history, who in his turn, through his creations, enabled a spotlight to be focused on a tiny fragment of the more than one thousand years of history of the city of Venice, helping us reconstruct the collective memory on which our present day is based.

Curated by Vittorio Pavan and Luca Del Prete, the exhibition is organised by the Veneto Museums Hub e Munus.

A couple of weeks ago I had the immense pleasure of cruising the Brenta Canal from Padua to Venice. I will be posting about that day soon, here, here and here. In the meantime: spoiler’s alert! In this post I chronicle our sailing out of the Canal and into the Venetian Lagoon.

I can promise you that everything changes immediately: the scale, the weather, our speed, the traffic, the feeling.

Last weekend I returned to Padua for another opportunity to see the Giotto frescoes at the Scrovegni Chapel. Since the visits are only 20 minutes long, it takes me more than one trip to Padua to really see the frescoes as I want to see them.

But, I also wanted to return to Padua to enjoy more of the city, now that I have discovered it fully. I went armed with my new fancy smartphone and its powerful camera. Some of the pictures below are of pretty Padova and some are just experiments with my camera.

I love any city with a street named for one of my favorite sculptors, Donatello.

The Botanic Garden of Padua dates back to 1545 and is regarded as the most ancient university garden in the world. Founded to foster the growth of medicinal plants, in Italian called semplice, since the remedies were obtained directly from nature without any manipulation. The garden was named Hortus Simplicium. The first keeper of the garden was Luigi Squalermo called Anguillara.

Nymphaea:

‘

Below, fall blooming crocus:

More water lilies:

Random plant life:

Nature with a background of Italian church bells:

Gigantic lily pads:

The horticultural complex in Padua is very impressive and state of the art.

Porta Portello:

Reminders of the influence of Venice on Padua are everywhere in this city:

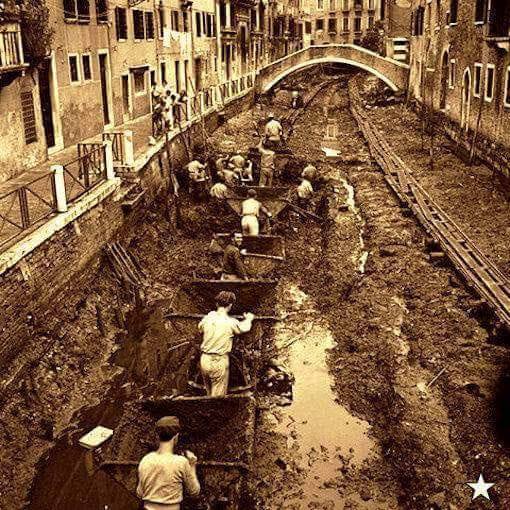

Padova is surrounded by water. The canals make lovely views. I love to think back to the times when people and goods moved here by gondole, burci and mascarete, all typical boats, along internal canals, following the waterways and floating under bridges.

Padua has a lot of beautiful architecture. I want to make another trip there to enjoy and photograph all the great sculptural embellishments on the palazzi.

Padova or Padua is a big subject! I’ve recently posted 2 times about it, here, here, here and here. And, still, I am far from done!

This post includes a list of the major features that grace this lovely, historic town. But first, a sweet little video about the town itself:

Undoubtedly the most notable things about Padova is the Giotto masterpiece of fresco painting in the The Scrovegni Chapel (Cappella degli Scrovegni). This incredible cycle of frescoes was completed in 1305 by Giotto.

It was commissioned by Enrico degli Scrovegni, a wealthy banker, as a private chapel once attached to his family’s palazzo. It is also called the “Arena Chapel” because it stands on the site of a Roman-era arena.

The fresco cycle details the life of the Virgin Mary and has been acknowledged by many to be one of the most important fresco cycles in the world for its role in the development of European painting. It is a miracle that the chapel survived through the centuries and especially the bombardment of the city at the end of WWII. But for a few hundred yards, the chapel could have been destroyed like its neighbor, the Church of the Eremitani.

The Palazzo della Ragione, with its great hall on the upper floor, is reputed to have the largest roof unsupported by columns in Europe; the hall is nearly rectangular, its length 267.39 ft, its breadth 88.58 ft, and its height 78.74 ft; the walls are covered with allegorical frescoes. The building stands upon arches, and the upper story is surrounded by an open loggia, not unlike that which surrounds the basilica of Vicenza.

The Palazzo was begun in 1172 and finished in 1219. In 1306, Fra Giovanni, an Augustinian friar, covered the whole with one roof. Originally there were three roofs, spanning the three chambers into which the hall was at first divided; the internal partition walls remained till the fire of 1420, when the Venetian architects who undertook the restoration removed them, throwing all three spaces into one and forming the present great hall, the Salone. The new space was refrescoed by Nicolo’ Miretto and Stefano da Ferrara, working from 1425 to 1440. Beneath the great hall, there is a centuries-old market.

In the Piazza dei Signori is the loggia called the Gran Guardia, (1493–1526), and close by is the Palazzo del Capitaniato, the residence of the Venetian governors, with its great door, the work of Giovanni Maria Falconetto, the Veronese architect-sculptor who introduced Renaissance architecture to Padua and who completed the door in 1532.

Falconetto was also the architect of Alvise Cornaro’s garden loggia, (Loggia Cornaro), the first fully Renaissance building in Padua.

Nearby stands the il duomo, remodeled in 1552 after a design of Michelangelo. It contains works by Nicolò Semitecolo, Francesco Bassano and Giorgio Schiavone.

The nearby Baptistry, consecrated in 1281, houses the most important frescoes cycle by Giusto de’ Menabuoi.

The Basilica of St. Giustina, faces the great piazza of Prato della Valle.

The Teatro Verdi is host to performances of operas, musicals, plays, ballets, and concerts.

The most celebrated of the Paduan churches is the Basilica di Sant’Antonio da Padova. The bones of the saint rest in a chapel richly ornamented with carved marble, the work of various artists, among them Sansovino and Falconetto.

The basilica was begun around the year 1230 and completed in the following century. Tradition says that the building was designed by Nicola Pisano. It is covered by seven cupolas, two of them pyramidal.

Donatello’s equestrian statue of the Venetian general Gattamelata (Erasmo da Narni) can be found on the piazza in front of the Basilica di Sant’Antonio da Padova. It was cast in 1453, and was the first full-size equestrian bronze cast since antiquity. It was inspired by the Marcus Aurelius equestrian sculpture at the Capitoline Hill in Rome.

Not far from the Gattamelata are the St. George Oratory (13th century), with frescoes by Altichiero, and the Scuola di S. Antonio (16th century), with frescoes by Tiziano (Titian).

One of the best known symbols of Padua is the Prato della Valle, a large elliptical square, one of the biggest in Europe. In the center is a wide garden surrounded by a moat, which is lined by 78 statues portraying illustrious citizens. It was created by Andrea Memmo in the late 18th century.

Memmo once resided in the monumental 15th-century Palazzo Angeli, which now houses the Museum of Precinema.

The Abbey of Santa Giustina and adjacent Basilica. In the 5th century, this became one of the most important monasteries in the area, until it was suppressed by Napoleon in 1810. In 1919 it was reopened.

The tombs of several saints are housed in the interior, including those of Justine, St. Prosdocimus, St. Maximus, St. Urius, St. Felicita, St. Julianus, as well as relics of the Apostle St. Matthias and the Evangelist St. Luke.

The abbey is also home to some important art, including the Martyrdom of St. Justine by Paolo Veronese. The complex was founded in the 5th century on the tomb of the namesake saint, Justine of Padua.

The Church of the Eremitani is an Augustinian church of the 13th century, containing the tombs of Jacopo (1324) and Ubertinello (1345) da Carrara, lords of Padua, and the chapel of SS James and Christopher, formerly illustrated by Mantegna’s frescoes. The frescoes were all but destroyed bombs dropped by the Allies in WWII, because it was next to the Nazi headquarters.

The old monastery of the church now houses the Musei Civici di Padova (town archeological and art museum).

Santa Sofia is probably Padova’s most ancient church. The crypt was begun in the late 10th century by Venetian craftsmen. It has a basilica plan with Romanesque-Gothic interior and Byzantine elements. The apse was built in the 12th century. The edifice appears to be tilting slightly due to the soft terrain.

Botanical Garden (Orto Botanico)

The church of San Gaetano (1574–1586) was designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi, on an unusual octagonal plan. The interior, decorated with polychrome marbles, houses a Madonna and Child by Andrea Briosco, in Nanto stone.

The 16th-century Baroque Padua Synagogue

At the center of the historical city, the buildings of Palazzo del Bò, the center of the University.

The City Hall, called Palazzo Moroni, the wall of which is covered by the names of the Paduan dead in the different wars of Italy and which is attached to the Palazzo della Ragione

The Caffé Pedrocchi, built in 1831 by architect Giuseppe Jappelli in neoclassical style with Egyptian influence. This café has been open for almost two centuries. It hosts the Risorgimento museum, and the near building of the Pedrocchino (“little Pedrocchi”) in neogothic style.

There is also the Castello. Its main tower was transformed between 1767 and 1777 into an astronomical observatory known as Specola. However the other buildings were used as prisons during the 19th and 20th centuries. They are now being restored.

The Ponte San Lorenzo, a Roman bridge largely underground, along with the ancient Ponte Molino, Ponte Altinate, Ponte Corvo and Ponte S. Matteo.

There are many noble ville near Padova. These include:

Villa Molin, in the Mandria fraction, designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1597.

Villa Mandriola (17th century), at Albignasego

Villa Pacchierotti-Trieste (17th century), at Limena

Villa Cittadella-Vigodarzere (19th century), at Saonara

Villa Selvatico da Porto (15th–18th century), at Vigonza

Villa Loredan, at Sant’Urbano

Villa Contarini, at Piazzola sul Brenta, built in 1546 by Palladio and enlarged in the following centuries, is the most important

Padua has long been acclaimed for its university, founded in 1222. Under the rule of Venice the university was governed by a board of three patricians, called the Riformatori dello Studio di Padova. The list of notable professors and alumni is long, containing, among others, the names of Bembo, Sperone Speroni, the anatomist Vesalius, Copernicus, Fallopius, Fabrizio d’Acquapendente, Galileo Galilei, William Harvey, Pietro Pomponazzi, Reginald, later Cardinal Pole, Scaliger, Tasso and Jan Zamoyski.

It is also where, in 1678, Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopia became the first woman in the world to graduate from university.

The university hosts the oldest anatomy theatre, built in 1594.

The university also hosts the oldest botanical garden (1545) in the world. The botanical garden Orto Botanico di Padova was founded as the garden of curative herbs attached to the University’s faculty of medicine. It still contains an important collection of rare plants.

The place of Padua in the history of art is nearly as important as its place in the history of learning. The presence of the university attracted many distinguished artists, such as Giotto, Fra Filippo Lippi and Donatello; and for native art there was the school of Francesco Squarcione, whence issued Mantegna.

Padua is also the birthplace of the celebrated architect Andrea Palladio, whose 16th-century villas (country-houses) in the area of Padua, Venice, Vicenza and Treviso are among the most notable of Italy and they were often copied during the 18th and 19th centuries; and of Giovanni Battista Belzoni, adventurer, engineer and egyptologist.

The sculptor Antonio Canova produced his first work in Padua, one of which is among the statues of Prato della Valle (presently a copy is displayed in the open air, while the original is in the Musei Civici).

The Antonianum is settled among Prato della Valle, the Basilica of Saint Anthony and the Botanic Garden. It was built in 1897 by the Jesuit fathers and kept alive until 2002. During WWII, under the leadership of P. Messori Roncaglia SJ, it became the center of the resistance movement against the Nazis. Indeed, it briefly survived P. Messori’s death and was sold by the Jesuits in 2004.

Paolo De Poli, painter and enamellist, author of decorative panels and design objects, 15 times invited to the Venice Biennale was born in Padua. The electronic musician Tying Tiffany was also born in Padua.

Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506) was an outstanding Italian Renaissance painter and engraver. He was also a student of Roman archeology, and the son-in-law of Jacopo Bellini.

Mantegna is best known for the Camera degli Sposi (“Room of the Bride and Groom”), or Camera Picta (“Painted Room”) (1474), in the Palazzo Ducale of Mantua. His other principal works include the Ovetari Chapel frescoes (1448–55) in the Eremitani Church in Padua and the Triumph of Caesar (begun c. 1486), the pinnacle of his late style. All of these works are discussed below or in later posts.

Born in Isola di Carturo, a part of the Venetian Republic and very close to Padua, Mantegna’s extraordinary native abilities were recognized early. He was the second son of a woodworker, but his artistic future was set in motion when he was legally adopted by Paduan artist, Francesco Squarcione, by the time he was 10 years old.

Squarcione was a teacher of painting and a collector of antiquities in Padua; the cream of young local talent were drawn to his studio. Some of Squarcione’s protégés, including Mantegna and another painter, Marco Zoppo, later had cause to regret being a part of the master’s studio.

Squarcione, whose original profession was tailoring, appears to have had a remarkable enthusiasm for ancient art, and a faculty for acting. Like his famous compatriot Petrarch, Squarcione was an ancient Rome enthusiast: he traveled in Italy, and perhaps also in Greece, collecting antique statues, reliefs, vases, etc., making drawings from them himself, then making available his collection for others to study. All the while, he continued undertaking works on commission, to which his pupils, no less than himself, contributed.

As many as 137 students passed through Squarcione’s school, which had been established around 1440 and which became famous all over Italy. Padua attracted artists not only from the Veneto but also from Tuscany, including such notables as Paolo Uccello, Filippo Lippi and Donatello.

Mantegna was said to be the favorite pupil of Squarcione, who taught him Latin and instructed him to study fragments of Roman sculpture. The master also preferred the used of a kind of forced pictorial perspective in his works, recollection of which may account for some of Mantegna’s later innovations.

In 1448, at age 17, Mantegna disassociated himself from Squarcione’s guardianship to establish his own workshop in Padua, later claiming that Squarcione had profited considerably from his services without giving due recompense.

Mantegna did not have to wait long for validation of his independence. The same year he was awarded a very important commission to create an altarpiece for the church of Santa Sofia in Padua.

Unfortunately, the altarpiece is now lost, but we know it demonstrated his precocity, for it was unusual for so young an artist to receive such a notable commission. Mantegna himself proudly called attention to his youthful ability in the painting’s inscription: “Andrea Mantegna from Padua, aged 17, painted this with his own hand, 1448.”

The same year, he was commissioned, together with Nicolò Pizzolo, to work with a large group of painters entrusted with the decoration of the Ovetari Chapel in the transept of another church in Padua, Sant’Agostino degli Eremitani (church of the Hermits of St. Augustine). Mantegna’s works in this church constitute his earliest surviving paintings.

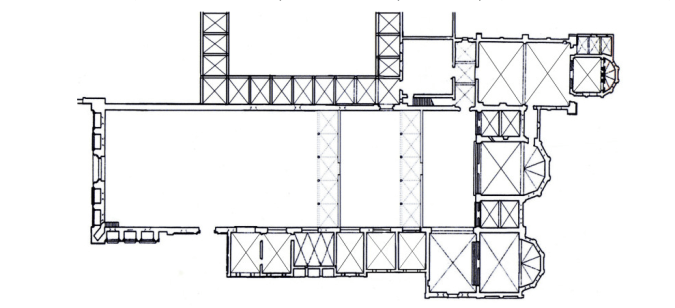

The facade of the Eremitani church, the Cappella Ovetari is in the right arm of the church’s transept.

Antonio Ovetari was a Padua notary who, at his death, left a large sum for the decoration of the family funerary chapel in the Eremitani church. The initial contracts for a series of frescoes were drawn up by the heirs of the notary in 1448. Works were commissioned from Giovanni d’Alemagna, Antonio Vivarini, Niccolò Pizzolo, and Mantegna. There is some indication that Mantegna (young as he was–17) may have been the originator of both the overall formal composition. The stories portrayed were inspired by The Golden Legend by Jacopo da Varazze.

According to the original agreement, the first two artists were to paint the arch with histories of the Passion of Christ (never executed), the cross vault and the right wall (Histories of St. Chrisopther) while the two Paduans would paint the rest, including the left wall (Histories of St. James, son of Zebedee) and the altar wall, with its windows, was to depict the Assumption of the Virgin.

Above, plan of the Eremitani Church in Padua.

The Cappella Ovetari fresco cycle:

Mantegna probably painted the left wall with the scenes from the life of St James, which have been almost totally lost. Here is a list of the scenes depicted:

Vocation of the Saints James and John

St. James Preaching

St. James Baptizes Hermogenes

Judgement of St. James

Miracle of St. James

Martyrdom of St. James

Fortunately, great restoration work continues in Italy and can be found here:

https://www.wga.hu/html_m/m/mantegna/01/index.html

https://www.2-people.com/project/ricostruzione-affreschi-cappella-ovetari/

These pictures can only give us a sense of how the wall once looked.

Above, overview of scenes from the Life of St James (scenes 1-6)

Scenes from the Life of St James (scenes 1-2)

Scenes from the Life of St James (scene 3)

Scenes from the Life of St James (scene 4)

Scenes from the Life of St James (scene 5)

Scenes from the Life of St James (scene 6)

2. Left (south) wall of Cappella Ovetari, Life of St. Christopher. The two scenes at the bottom (scenes 5 and 6) are by Mantegna.

Here is a list of the scenes depicted:

St. Christopher Leaving the King by Ansuino da Forlì (attributed)

St. Christopher and the King of the Devils by Ansuino da Forlì (attributed)

St. Christopher Ferrying the Child by Bono da Ferrara (signed)

St. Christopher Preaching by Ansuino da Forlì (signed)

Martyrdom of St. Christopher by Andrea Mantegna

Transportation of St. Christopher Beheaded Body by Andrea Mantegna.

Scenes from the Life of St Christopher (scenes 1-2)

Scenes from the Life of St Christopher (scene 3)

Scenes from the Life of St Christopher (scene 4)

Scenes from the Life of St Christopher (scene 5)

Scenes from the Life of St Christopher (scene 6)

3. The altar wall is for the most part the work by Mantegna: Assumption of the Virgin

4. The apse was divided into sections: Mantegna painted the saints Peter, Paul and Christopher within a stone frame decorated with festoons of fruit. These figures show similarities with the frescoes by Andrea del Castagno in the Venetian church of San Zaccaria (1442), both in the format and their sculptural firmness. Also similar is the cloud on which the figures are standing.

The remaining spaces were painted with images of the Eternal Father Blessing and the Doctors of the Church by Niccolò Pizzolo. The Doctors were depicted as majestic figures, and the saints were shown as Humanist scholars at work in their studios.

The arch was painted with two large heads, usually identified as self-portraits by Mantegna and Pizzolo.

5. The vault was decorated with Four Evangelists by Antonio Vivarini between festoons by Giovanni d’Alemagna.

6. A terra-cotta altarpiece completes the decoration of the chapel. It is covered with bronze by Pizzolo, and is extremely damaged. It shows a Sacra Conversazione in bas-relief.

Next, the history of the way the contract was executed by the painters.

Phase 1:

Already in 1449, there were personal problems between Mantegna and Pizzolo, the latter accusing the former of continuous interference in the execution of the chapel’s altarpiece. This led to a redistribution of the works among the artists; perhaps due to this Mantegna halted his work and visited Ferrara.

In 1450, Giovanni d’Alemagna, who had executed only the decorative festoons of the vault, died; the following year Vivarini left the work after completing the depictions of the four Evangelists in the vault. Those 2 artists were replaced by Bono da Ferrara and Ansuino da Forlì, whose style was influenced by that of Piero della Francesca.

Mantegna began to work from the apse vault, where he placed images of three saints. Pizzolo painted images of the Doctors of the Church.

Next, Mantegna likely moved to the lunette on the left wall, with the Vocation of Saint James and St. John, and the Preaching of St. James, completed within 1450, and then moved to the middle sector.

Phase 2:

At the end of 1451 work was suspended due to lack of funds. They were restarted in November 1453 and completed in 1457. This second phase saw Mantegna alone at work, as Pizzolo had also died in 1453. Mantegna completed the Stories of St. James, frescoed the central wall with the Assumption of the Virgin and then completed the lower sector of the Stories of St. Cristopher begun by Bono da Ferrara and Ansuino da Forlì. Here Mantegna painted two unified scenes dealing with the subject of the Martyrdom of St. Christopher.

In 1457. Imperatrice Ovetari sued Mantegna, accusing him of having painted, in the Assumption, only eight apostles instead of twelve. Two painters from Milan, Pietro da Milano and Giovanni Storlato, were called in to solve the matter. They justified Mantegna’s choice due to the lack of space.

Subsequent history:

Fortunately, sometime around 1880, two of the scenes, the Assumption and the Martyrdom of St. Christopher, were detached from the church walls to protect them from dampness. They were stored in a separate location and thus not destroyed during WWII.

During the war, those two frescoes were saved from the air bombardment that destroyed of all the rest of the cycle on 11 March 1944. Luckily, black-and-white photographs of the frescoes taken before the bombing allow us to visually reconstruct the cycle. First, let us look at images of the church taken after the bombings.

The 20th century bombing:

The restoration of the chapel’s frescoes:

The fresco cycle of the Ovetari chapel was, like almost all of the church’s interior, destroyed by an Allied bombing in March of 1944: today, only two scenes and a fragments survive. Painstaking work by talented art restorers have produced an almost unbelievable job of reconstituting the fragments into a whole, unveiled in 2006. The restorers had black-and-white photographs to guide their work.

Below are the photos I took on my recent visit to Padua.

The rich history of Padua was only partially discussed here. This post continues the story.

The Carrara Family, also called Carraresi, was a medieval Italian family who ruled first as feudal lords about the village of Carrara in the countryside near Padua and then as moderately enlightened despots in the city of Padua.

Having moved into Padua itself in the 13th century, the Carraresi exploited the feuds of urban politics first as Ghibelline and then as Guelf leaders and were thus able to found a new and more illustrious dominion. The latter began with the election of Jacopo da Carrara as perpetual captain general of Padua in 1318 but was not finally established, with Venetian help, until the election of his nephew Marsiglio in 1337.

For approximately 50 years, the Carraresi ruled with no serious rivals except among members of their own family. Marsiglio was succeeded without incident by Ubertino (1338–45), but Marsigliello, who succeeded Ubertino, was deposed and murdered by Jacopo di Niccolò (1345–50).

Jacopo was then murdered by Guglielmino and succeeded by his brother Jacopino di Niccoló (1350–55), and Jacopino in turn was dispossessed and imprisoned by his nephew Francesco il Vecchio (1355–87). Such a nice family to call your own.

Despite this chaos, the Carrara court was one of the most brilliant in all of the Italian peninsula. Ubertino in particular was a patron of building and the arts, and Jacopo di Niccolò was a close friend of Petrarch.

Only with the exception of a brief period of Scaligeri (the ruling family in Verona) overlordship between 1328 and 1337 and two years (1388–1390) when Giangaleazzo Visconti held the town, Padua was pretty much owned by the Carraresi.

The many advances of Padova in the 13th century naturally brought the commune into conflict with Can Grande della Scala, lord of Verona. In 1311, Padua had to yield.

But, even under the Carraresi, it was a long period of restlessness, for the Carraresi were constantly at war. Under Carraresi rule, the early humanist circles at the University of Padua were effectively disbanded: Albertino Mussato, the first modern poet laureate, died in exile at Chioggia in 1329, and the eventual heir of the Paduan literary tradition went to the Tuscan Petrarch.

In 1387, John Hawkwood won the Battle of Castagnaro for Padua, against Giovanni Ordelaffi, for Verona.

The Carraresi period finally came to an end as the power of the Visconti and of Venice grew in importance. Padova came under the rule of the Republic of Venice in 1405, and mostly remained that way until the fall of the Republic of Venice in 1797.

There was just a brief period when the city changed hands (in 1509) during the wars of the League of Cambrai. Padova was held for just a few weeks by Imperial supporters, but Venetian troops quickly recovered it and successfully defended Padua during a siege by Imperial troops (Siege of Padua).

As a part of the Venetian Republic, Padova was governed by two Venetian nobles, a podestà for civil affairs and a captain for military affairs. Each was elected for 16 months. Under these governors, the great and small councils continued to discharge municipal business and to administer the Paduan law, contained in the statutes of 1276 and 1362. The treasury was managed by two chamberlains; and every five years the Paduans sent one of their nobles to reside as nuncio in Venice; this elected official was in place to watch out for the interests of his native town.

For more information see: https://digilander.libero.it/clapad5/padova/mura.html

1. The Romans would seem to be the first to surround Padova with walls. Of the walls built during the ancient Roman era, the only traces to survive are those incorporated into the foundations of certain palazzi. The route of these walls corresponded to a meandering line formed by the river Medoacus (now the Brenta). Inside the walls, Padua’s first urban center developed.

2. The Mura Duecentesche (“13th century walls”; aka the mura comunali or mura medievali) were built at the start of the 13th century by the Comune of Padua. Their route was delimited by the two branches of the Bacchiglione, the Tronco Maestro and the Naviglio Interno, which came to be used as defensive ditches. There are several remains of them around the Castello and near Porta Molino. More minor remains are to be found in the Riviera Tito Livio and Riviera Albertino Mussato; the only gates to remain from this wall are the main north gate, Porta Molino (or Molini, after several mills in the area which functioned up to the early 20th century), and the main west gate, Porta Altinate (named after the road to Altino which began here).

(The Porta Molino‘s upper stories were used at the end of the 19th century as a reservoir for the town’s first drinking water system; tales of the tower being used as an observatory by Galileo Galilei during his time in the city are probably false. The Porta Altinate fronted onto the Naviglio Interno, crossed by an ancient Roman three-arch bridge, and in 1256 this gate was stormed and destroyed by crusaders fighting against Ezzelino da Romano [as recorded in an inscription recorded by Carlo Leoni]. It was rebuilt in 1286. The Naviglio and the bridge were buried in the 1960s.)

3. 14th century, the Mura Carraresi were built by the Carraresi in the 14th century and followed a route that would be followed almost by the later 16th century wall. Almost nothing remains of them the Mura Carraresi, since they were demolished during the War of the League of Cambrai to create the Renaissance wall. However, some sections can be seen in via delle Dimesse, near the Prato della Valle.

4. The Mura Cinquecentesche (16th century Walls; aka the Mura rinascimentali or Mura Veneziane) were built to protect Padova by the Venetian Republic during the first decades of the 16th century. It was a project of the condottiero Bartolomeo d’Alviano.

Canaletto, View of Padua from outside the city walls with the Church of San Francesco and the Palazzo della Salone

The Mura rinascimentali were protected on their west flank by a canal known as the fossa Bastioni, which still exists. The Renaissance walls survive to this day, almost entirely unbroken apart from sections demolished in the 1960s to build the new Ospedale Civile.

Nearly all the walls’ gates survive. For even more information, see: http://digilander.libero.it/clapad5/padova/porte.html

Porta Savonarola – Completed in 1530. Designed by the architect Giovanni Maria Falconetto, this gate was built with a frieze showing the Lion of Saint Mark, symbol of the Venetian Republic, which still survives. Picture below:

Porta san Giovanni – Completed in 1528. Designed by the architect Giovanni Maria Falconetto, this gate originally had a frieze showing the Lion of Saint Mark, symbol of the Venetian Republic (the frieze here was destroyed during the Napoleonic Wars). Picture below:

Porta Ognissanti (or Portello, Portello Nuovo or Portello Venezia) – Originally entitled Portello or Little Port, the gate was built at the terminus for the river trade along the Brenta between Padua and Venice. The present building replaces the Portello Vecchio, on what is now via San Massimo, but is rather different from the city’s other gates of this date – the external facade is adorned with shining rocks from Istria, with four pairs of columns surmounted by an architrave embellished with four trachyte cannonballs. The three-arch bridge carrying the road over the Canale Piovego and through the gate is guarded by two white stone lions. Stones in the gate (still legible today) commemorate the ancient origins of the town, speaking to “its good governance.” Since 1535, a clock stands out from the gate in Nanto stone. Traces of frescoes can also be seen inside the gate. 5 pictures below:

Porta Liviana – Begun in 1509, it was completed in 1517 and named in honour of Bartolomeo d’Alviano himself.

Porta Santa Croce – On the site of a gate in the Carraresi wall, the present gate was begun in 1509 and was originally defended by a tower, demolished in 1632.

(For a walk to view the city walls, you can start from Piazza Garibaldi, where there is the medieval Porta Altinate (1286), one of the 3 oldest city gates, with short sections of walls still visible at various points of the Ponte Romani and Tito Livio rivers, then walk along via San Fermo (with the church of the same name leaning against the city walls). Walk from the Largo Europe and the Riviera Mugnai until you reach the intersection with via Dante, then you arrive at the 2nd medieval gate, Porta Ponte Molino, with its large pointed arch surmounted by a mighty tower.)

In 1797, the Venetian Republic came to an end with the Treaty of Campo Formio, and Padua, like much of the Veneto, was ceded to the Habsburgs. In 1806, the city passed to the French puppet Kingdom of Italy until the fall of Napoleon, in 1814, when the city became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, part of the Austrian Empire.

Austrian rule was unpopular with progressive circles in northern Italy, but the feelings of the population (from the lower to the upper classes) towards the empire were mixed.

In Padua, the year of revolutions of 1848 saw a student revolt which on 8 February turned the University and the Caffè Pedrocchi into battlegrounds where students and Paduans fought side by side. The revolt was, however, short-lived and there were no further episodes of unrest under the Austrian Empire (nor previously had there been any), as in Venice or in other parts of Italy. The opponents of Austria were forced into exile.

Under Austrian rule, Padua began its industrial development; one of the first Italian rail tracks, Padua-Venice, was built in 1845. In 1866, the Battle of Königgrätz gave Italy the opportunity, as an ally of Prussia, to take Veneto, and Padova was also annexed to the recently formed Kingdom of Italy.

At that time, Padova was at the center of the poorest area of Northern Italy, as the Veneto was until the 1960s. Despite this, the city flourished in the following decades both economically and socially, developing its industry, being an important agricultural market and having a very important cultural and technological center as the University. The city hosted also a major military command and many regiments.

When Italy entered World War I on 24 May 1915, Padova was chosen as the main command of the Italian Army. The king, Vittorio Emanuele III, and the commander in chief, Cadorna, lived in Padua for the period of the war.

After the defeat of Italy in the battle of Caporetto in autumn 1917, the front line became the river Piave, only about 35 miles from Padua. This put the city in the range of the Austrian artillery. However, the Italian military command did not withdraw. The city was bombed several times, with about 100 civilian deaths. A memorable feat was Gabriele D’Annunzio’s flight to Vienna from the nearby San Pelagio Castle airfield.

In 1918, the threat to Padua was removed. In late October, the Italian Army won the decisive Battle of Vittorio Veneto, and the Austrian forces collapsed. The armistice was signed at Villa Giusti, Padua, on 3 November 1918.

During the war, industry grew rapidly, and this provided Padua with a base for further post-war development. In the years immediately following WWI, Padua grew outside the historical town, despite the fact that labor and social strife were rampant at the time.

As in many other areas in Italy, Padua experienced great social turmoil in the years immediately following World War I. The city was shaken by strikes and clashes, factories and fields were subject to occupation, and war veterans struggled to re-enter civilian life. Many supported a new political way, fascism.

As in other parts of Italy, the National Fascist Party in Padua soon came to be seen as the defender of property and order against revolution. Padua was the site of one of the largest fascist mass rallies, with some 300,000 people reportedly attending one speech by Benito Mussolini.

New buildings, in fascist architectural style, sprang up in the city. Examples can be found today in the buildings surrounding Piazza Spalato (today Piazza Insurrezione), the railway station, the new part of City Hall, and part of the Palazzo Bo hosting the University.

Following Italy’s defeat in WWII on 8 September 1943, Padua became part of the Italian Social Republic, which was a puppet state of the Nazi occupiers. The city hosted the Ministry of Public Instruction of the new state, as well as military and militia commands and a military airport.

The Resistenza, the Italian partisans, was very active against both the new fascist rule and the Nazis. One of the main leaders of the Resistenza in the area was the University vice-chancellor Concetto Marchesi.

Toward the end of the war, as the Allied Command freed Italy from German occupation moving from south to north, Padua was unfortunately bombed several times by Allied planes. The worst hit areas were the railway station and the northern district of Arcella. Because of the location of the German command center in Padua, it was during one of these bombings that the Church of the Eremitani took a direct hit. It was a miracle of sorts that the nearby Scrovegni Chapel was not hit as well.

You can see on the map below how close the Scrovegni is to the church (Chiesa degli Eremitani on the map).

Tragically, the Church of the Eremitani was graced with some of the finest frescoes by Andrea Mantegna and they were almost complete obliterated. This is considered by some art historians to be Italy’s biggest wartime cultural loss.

Art conservators have been able to do the almost impossible and stitch together the remnants of the frescoes as seen in the next picture. I’ll be posting about the frescoes soon.

The city was liberated by partisans and the 2nd New Zealand Division of the British Eighth Army on 28 April 1945. A small Commonwealth War Cemetery is located in the west part of the city, commemorating the sacrifice of these troops.

After the war, the city developed rapidly, reflecting Veneto’s rise from being the poorest region in northern Italy to one of the richest and most economically active regions of modern Italy.

The subject of Padua is vast. I’ll be posting yet more very soon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.