Read more: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-monuments-men-saved-

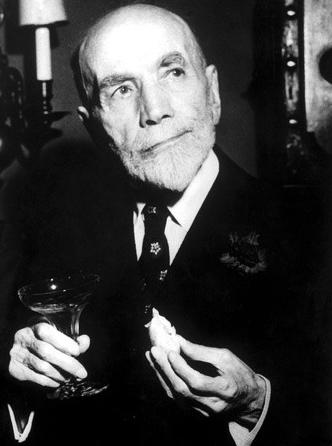

It had been a kind of liberation, of both mind and desire, that Berenson had discovered in reading the works of Walter Pater and in beginning to study the paintings of the Italian Renaissance, and this still rang through to his visitors seventy years later. Lewis Mumford wrote to Berenson of a visit in 1957, “To behold your own spirit burning so purely and brightly still, gave a new meaning to Pater’s old figure: ‘a hard gem-like flame.’”

With Katherine Dunham, the African American anthropologist, choreographer,and dancer, Berenson had a sort of platonic love affair when he was just shy of ninety. He wrote that Dunham “is herself a work of art, a fanciful arabesque in all her movements and a joy to the eye in colour.” She from the first felt in him the “vitality, charm, and wisdom that are found only in truly great people” and would eventually write to him, “I left a part of myself that is deep and inner with you.”

Rachel,Cohen. Bernard Berenson (Jewish Lives) Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

This is just something I never would have believed had happened, but it apparently did. It is discussed in a very interesting book on Berenson by Rachel Cohen, which I quote below. Lee Radziwill left her impression of the sophisticated but very much older Berenson:

“Nicky Mariano [Berenson’s amour and assistant) was sometimes jealous…of Berenson’s flirtations and affairs and of the great many women who made up what she called ‘B.B.’s Orchestra.’ “

In fact, as he aged, Berenson’s seductive power became somewhat legendary. Lee Radziwill (Lee Bouvier when she visited Berenson in 1951 with her sister, who became Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis) still thought of Berenson as “one of the most fascinating men I ever knew,” sixty years later. She compared his powerful appeal to Jawaharlal Nehru’s: they were “seductive mentally, rather than physically.”

Berenson’s catalog of mistresses and of epistolary romances, like all his other collections, was exhaustive. He had first found both sexual tolerance and a large network of youthful romantic friendships with women and men in bohemian and Edwardian circles, and among the expatriates in Italy.

In the years of his maturity, he found a similar atmosphere among his mistresses and flirtations in the aristocratic milieu of the European art world. Berenson adored, and was adored by, titled women, and he was interested in beauty wherever he saw it. Attractive young women who visited I Tatti were regularly surprised by his physical attentions.

After WWII…Berenson nce again he appeared to be a magician. There were those who found his presence staged, but others felt that even to be near him was a magical experience.

The young sisters who became Jackie Kennedy and Lee Radziwill wrote to their mother of visiting Berenson in the summer of 1951 and of how they saw him approaching through the woods at I Tatti. Berenson sat down and immediately began to speak to them of love, distinguishing between people who are “life-enhancing” and “life-diminishing.”

“He is a kind of god like creature,” they wrote. “He is such a genius, such a philosopher, such a pillar of strength and sensitivity, and such a lover of all things. He is a man whose life in beauty is unsurpassable.”

Rachel,Cohen. Bernard Berenson (Jewish Lives) Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

Papal excess, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Stephen Colbert.

Before Charles Eliot Norton had become Harvard’s first professor of that discipline, art history had, in general, been considered, not a field of study, but a matter of craft and technique to be taught by painters to other painters.

Scholarship about art, and especially about Italian art, entered a new era as the German universities began developing large-scale historical studies like those of Swiss scholar Jacob Burckhardt, whose Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy was published in English in 1878.

In Great Britain, tastes were influenced by the work of Norton’s close friend Ruskin in books like The Stones of Venice (1851–1853) and The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849).

Following Ruskin, Norton loved best in Italy the powerful moral uplift of Dante and of Italy’s medieval Gothic architecture. In Norton’s art history courses, the Renaissance was the unhappy termination of the Middle Ages, which had been the last great era of spiritual unity and well-being.

There was a joke current among Harvard undergraduates that Norton had died and was just being admitted to Heaven, but at his first glimpse staggered backward exclaiming, “Oh! Oh! Oh! So Overdone! So garish! So Renaissance!”

“Norton,” Bernard Berenson commented drily years later, had done what he could at Harvard to restrain “all efforts toward art itself.”

Rachel,Cohen. Bernard Berenson (Jewish Lives) (p. 45). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

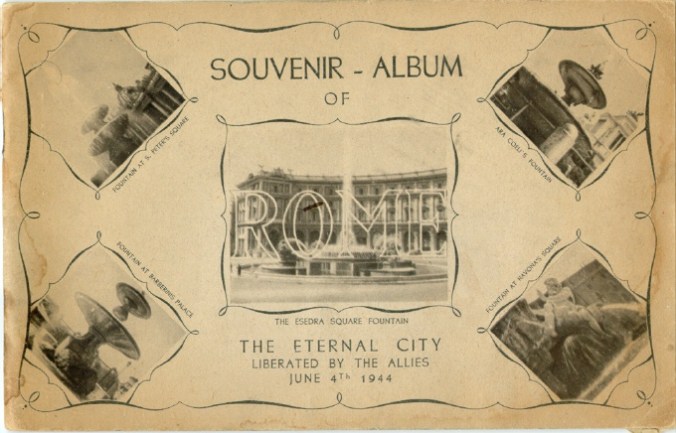

“Trapani! Trapani, don’t you see?” [British] Capt. Edward Croft-Murray exclaimed as the skyline of the Sicilian coastal town first appeared through the porthole of the Allied aircraft. [The Brit] Sitting next to him, Maj. Lionel Fielden, who had been drifting off into daydream for much of the flight from Tunis, opened his eyes to the landscape below. “And there, below us,” Fielden later wrote, “swam through the sea a crescent of sunwashed white houses, lavender hillsides and rust red roofs, and a high campanile whose bells, soft across the water, stole to the mental ear. No country in the world has, for me, the breathtaking beauty of Italy.”

…As soon as the first Monuments Officers reached Sicily, the implications of such a mandate [to preserves as many cultural works as possible] proved as difficult as its scope was vast. The Italian campaign, predicted to be swift by Allied commanders, turned into a 22-month slog. The whole of Italy became a battlefield. In the path of the Allied armies, as troops slowly made their ascent from Sicily to the Alps, lay many beautiful cities, ancient little towns and innumerable masterpieces. As General Mark Clark declared with frustration, fighting in Italy amounted to conducting war “in a goddamn museum.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.