ON JULY 4, the same day Keller arrived in Siena, Superintendent of Florentine Galleries Giovanni Poggi received a summons to report to the German Military Commander of Tuscany, Colonel Metzner. With barely a greeting, Metzner asked “if Villa Bossi-Pucci in Montagnana contained works of art of such importance to require their transportation across the Apennines” to northern Italy?

Poggi, fluent in both German and French, was surprised by Metzner’s sudden mention of Montagnana, site of the Villa Bossi-Pucci, which served as one of Tuscany’s thirty-eight art repositories. The constant shifting of the battlefield had prevented Poggi and his team from reaching many of the Tuscan repositories, but the Germans had no such impediment.

Metzner’s sudden curiosity about the Villa Bossi-Pucci—which housed close to three hundred masterpieces from the Uffizi Gallery and the Palatine Gallery at the Pitti Palace, including Botticelli’s Minerva and the Centaur, Giovanni Bellini’s Pietà, and Caravaggio’s Sleeping Amor—was cause for great concern. By July 1944, few men in the world had more hands-on experience protecting works of art than Poggi, a native Florentine described by Hartt as “a character who walked out from one of Ghirlandaio’s frescoes.”

Poggi oversaw a domain that included the provinces of Florence, Arezzo, and Pistoia. At age sixty-four, he had lived long enough to witness war engulf his homeland twice. Fate selected Poggi to be a defender of the arts. An illustrious connoisseur and curator, he had been appointed Director of the esteemed Uffizi Gallery in 1912, at the age of thirty-two.

The following year, he helped recover the world’s most famous painting, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, stolen from the Louvre in 1911. The painting had been missing for more than two years before surfacing in a Florence hotel. After a brief showing at the Uffizi, and a tour through Italy, Poggi accompanied the painting back to Paris in December 1913.

Just six months later, the outbreak of the Great War consumed Europe. The burning of the library in Louvain galvanized art officials across the continent. Few if any nations had more at risk than Italy, no single city more than Florence. Poggi’s quick work protecting the Uffizi’s treasures drew the attention of officials in Rome. Soon they enlisted his aid in safeguarding prominent masterpieces in other Italian cities.

Now, for the second time in twenty-six years, Poggi found himself responsible for protecting the treasures of Tuscany from a world at war. Poggi calmly answered Metzner’s question, telling him that there were indeed highly important works from the galleries and museums of the State in Montagnana.

But, “due to agreements taken with the General Direction of the Arts and with the Office directed by Colonel Langsdorff, it had been decided, as with the other repositories, not to remove anything unless there were some urgent peril, and in that case paintings would have been moved to Florence and not across the Apennines.” Unfazed, Metzner pressed Poggi further, asking in an ominous tone, “So you are rejecting our offer?” Ten months of dealing with German officers had taught Poggi to appeal to their authority—and ego. He explained: “We are not rejecting it, on the contrary, we are grateful. We accept it in the event that it becomes necessary to move these things to Florence.” The meeting concluded soon thereafter; Poggi assumed his replies had settled the matter.

THE OUTBREAK OF war in 1940 had caused Italian superintendents to transfer collections to areas outside the city centers. Acting with “frenzied lucidity,” Poggi and his team had moved almost six hundred major works to privately owned villas and palaces in the Tuscan countryside in less than two weeks. That number had increased more than eighteenfold—to 11,139 various art objects—within six weeks. Those that couldn’t be moved, usually due to their size and weight, had to be protected in situ, often by employing the most ingenious of methods.

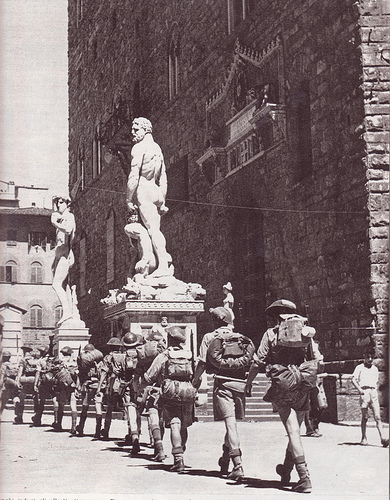

Local artisans built a brick tomb around Michelangelo’s towering sculpture of David, and smaller ones for each of his adjacent works, referred to as the Slaves. Poggi hoped that these brick silos would provide protection against bomb fragments or even the collapse of the roof in the event of a direct hit on the building. With the dramatic increase in Allied bombing of Italian cities in the fall of 1942, Poggi and other superintendents received orders to make additional evacuations from the cities.

This required him to secure more villas for storage. The groupings of art were historic. Villa di Torre a Cona contained not only Michelangelo’s statues from the Medici tombs in the Church of San Lorenzo but all of the contents of the master’s family home, Casa Buonarroti. This collection contained two of his earliest works and many of his letters and drawings. Never before had so many of Michelangelo’s works

been gathered in one place. Sitting alongside were masterpieces by Verrocchio, Donatello, Della Robbia, Lorenzo Monaco, and the most important surviving work by the Flemish painter Hugo van der Goes, the Portinari Altarpiece. The quality and rarity of the art was simply staggering. The Castle of Montegufoni housed 246 masterpieces from the Uffizi and the Pitti by great masters such as Cimabue, Giotto, Botticelli, Raphael, Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo, and Rubens.

The repository at Poppiano sheltered Pontormo’s emotive masterpiece, Deposition from the Cross, from the Capponi Chapel in the Church of Santa Felicita, and Rosso Fiorentino’s crowning achievement, Descent from the Cross, from the town of Volterra. The Palazzo Pretorio at Poppi held Hans Memling’s Portrait of a Young Man and Michelangelo’s Mask of a Faun; the Oratory of Sant’Onofrio at Dicomano contained Roman sculptures and sarcophagi; the villa at Poggio a Caiano housed Donatello’s Saint George and Michelangelo’s Bacchus. The quality and importance of each villa’s contents surpassed the last, each filled with the accomplishments of civilization’s most creative minds. The fall of the Badoglio-led government and the occupation of Italy by German forces in September 1943 prompted most Italian art officials, including Lavagnino and Rotondi, to relocate their collections to the Vatican. But Poggi made the decision to keep the Tuscan artworks within his reach at their existing countryside repositories.

These villas, he believed, afforded more protection from aerial attack than any fortress in an urban setting. By the time he realized that the Tuscan repositories lay in the path of the coming ground battle, it was too late to return all of the works of art to Florence. And that gave rise to another concern, one he could do nothing about: perhaps overconfident at the time, Poggi had allowed many of the masterpieces to be transported from Florence uncrated. Poggi certainly knew that the safest place for a painting was hanging on the wall of a museum.

Once it began a journey, the risks of damage increased dramatically. Moving uncrated paintings in trucks exposed them to dust. Canvases were vulnerable to tears, punctures, and scratches. Vibration alone could cause the wood of a panel painting to split. Poggi also knew well that paintings on panel are reactive to sudden changes in humidity. Low humidity during winter weather diminishes the moisture in the wood, increasing the risk it might crack. Sculpture, whether marble (more durable) or terra-cotta (more fragile), was always at risk of being chipped, much less ruined if dropped. Subsequent moves would compound these risks even further,

SS Colonel Alexander Langsdorff, head of the Kunstschutz, to discuss how best to protect the Florence repositories from the looming battle. Anti insisted that the treasures be evacuated again and moved north, but his argument ignored the shortage of transportation and the speed with which enemy troops were approaching Tuscany. After a heated discussion, Poggi prevailed. The art would remain in the existing repositories. “It is too late,” Anti noted ominously in his diary.

In early July, Social Republic officials once again pressed for the works of art to be transported northward. Certain that he knew what was best for “his” works of art, Poggi shrewdly parried the request with the Medici Family Pact of 1737, which required that their collection (the core of the Uffizi and Pitti collections) “never be removed or taken outside its capital and the Grand Duchy.” At this stage of the war, Poggi had no real power to keep Fascist officials or the Germans from removing works of art. Clever excuses and tricks were his only tools.

Several days later, Poggi received a shocking telephone call from the German Consul, Dr. Gerhard Wolf, informing him that Wehrmacht troops had loaded 291 paintings from the Villa Bossi-Pucci repository at Montagnana onto trucks and taken them to the small town of Marano sul Panaro near Modena, some ninety miles north of Florence. This was the same villa Colonel Metzner had questioned Poggi about just days earlier. “At one blow at least an

eighth of the most prized contents of the Uffizi and Pitti had vanished.” Further queries by Consul Wolf later revealed the treachery: the paintings had been taken—and were already en route north—before Metzner’s portentous meeting with Poggi on July 4. Gerhard Wolf requested that Langsdorff report to Florence to resolve the matter. Without transportation, Poggi could do nothing. On Sunday evening, July 16, Poggi received a call from Consul Wolf’s assistant, advising him that a different German unit had removed works of art from a second, as-yet-unidentified repository. Poggi should expect to take custody of them at German Military Headquarters, in Florence’s Piazza San Marco, the next day at 8 a.m.

With no sign of Langsdorff, and no further word about the disposition of the artworks from Villa Bossi-Pucci, this latest news horrified and infuriated Poggi. The following morning, Poggi and other officials watched three German trucks pull into Piazza San Marco, right on time. The officer in charge of the operation, Colonel Hoffmann, informed them “that since the castle of Oliveto was under the fire of the Allied artillery, the military command of the area had decided on the immediate transport to Florence of the works of art.” The unloading of paintings commenced, notably those from the Horne Foundation museum and altarpieces from the city’s churches—eighty-four paintings, twenty-three crates, and five frames. For reasons Hoffmann didn’t explain, more than one hundred paintings had been left behind. While Poggi tried to make sense of it all, the custodian of the repository at the Castello Guicciardini in Oliveto, Augusto Conti, who had accompanied the trucks into Florence, discreetly informed him that Hoffmann’s explanation was a lie. The area around the castello had been quiet, void of any combat activity. Conti then shared even more distressing news.

Two panel paintings by German Renaissance painter Lucas Cranach the Elder—Adam and Eve—had been loaded into an ambulance. He had no idea what had happened to them after that. Poggi knew both paintings well—and he knew that Hitler did too. During the Führer’s 1938 tour of the Uffizi, Poggi remembered watching how much Hitler had admired the German painter’s works. The disappearance of such masterpieces, which had entered the collection of the Medici in the late eighteenth century, caused great alarm among Florentine officials. Langsdorff finally arrived in Florence on July 17.

Poggi assumed he could rely on the senior representative of the Kunstschutz, just as he had in May, when Langsdorff had provided cranes, trucks, and personnel to return Ghiberti’s Baptistery doors to the Pitti Palace. Poggi began by informing Langsdorff of the removals from the Castello Guicciardini in Oliveto that Colonel Hoffmann had delivered just hours earlier. That a portion of the contents from the Oliveto repository never made it to Florence, in particular the two Cranach paintings of Adam and Eve, worried him.

These removals violated the agreement made among Poggi, Carlo Anti, and Langsdorff at their June 18 meeting: in the event of any emergency evacuations of repositories, works of art were to be brought to Florence. Under no circumstances could this occur again. Langsdorff assured Poggi that not only would he investigate what had happened to the missing items, he would accept full responsibility for locating and returning the Cranach paintings to Florence. As part of his investigation, Langsdorff asked Poggi to prepare a memorandum summarizing what he knew about the removal of art from the Villa Bossi-Pucci. When the report was completed, he wanted it delivered to the Hotel Excelsior, where he had a room overlooking the Ponte Santa Trinita and the Ponte Vecchio.

This response hardly satisfied Poggi, but, under the circumstances, he could do little else. News of continued Allied advances forced Langsdorff to reassess orders he had received from Army High Command (OKH) three days earlier, stating, “The rescue of art objects by the troops has to generally be stopped.” The order also included a directive stating that any art objects that had already been removed should be turned over to the “bishops of Bologna or Modena.” German troops had in fact attempted a delivery of the Montagnana items, but the bishops had turned them away, stating they didn’t have sufficient space to store the items nor did they have authority to accept such responsibility. Cranach paintings, and he repeated his promise to find and return them to Florence. What Langsdorff didn’t tell Poggi was that the Cranachs were already safe. In fact, they were in his possession, “handed over by the troops . . . asking me to take them north, so that they would not fall into the hands of the British or the Americans.” In the course of his debriefing of Infantry Regiment 71’s Oberleutnant Feldhusen in Oliveto, Langsdorff learned that the Cranachs had been “separated from the rest because they were ‘Germanic art’ and could not be exposed to the danger of being returned to Florence.” Never mind the fact that Infantry Regiment 71 had traveled those same unsafe, bomb-cratered roads into Florence two nights earlier. He then wrote out a receipt for “two undamaged pictures, Adam and Eve, by Lukas Cranach which are to be taken to Germany by the undersigned, MV Abt. Chef Langsdorff,” and handed it to the Oberleutnant. Using the safe passage afforded by an ambulance, Langsdorff and his “passengers”—Adam and Eve—set out for Florence, just as he had assured Poggi he would do. Wednesday evening, July 19, Poggi stopped by the Hotel Excelsior to visit with Langsdorff and deliver the memorandum he’d been asked to prepare concerning the Montagnana removals. Much to Poggi’s surprise, Langsdorff had already checked out and departed Florence. Had Poggi thought to ask the concierge, he might have learned that Langsdorff left the hotel with two life-size parcels that, oddly enough, had arrived two nights before in an ambulance. In just two weeks, Poggi had been duped by the German Military Commander of Florence, Colonel Metzner, and lied to by the officer who delivered the works of art from Oliveto, Colonel Hoffmann. But those two betrayals paled in comparison to the disappointment he felt toward Langsdorff. Unlike the other two officers, Langsdorff was the senior German Kunstschutz official in Italy. He had an obligation to protect art, not to steal it.

Edsel, Robert M.. Saving Italy: The Race to Rescue a Nation’s Treasures from the Nazis (pp. 148-149). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.

You must be logged in to post a comment.