“They are immense stretches of wheat fields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness.”– Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother and sister-in-law shortly before his death.

This article is excerpted from “Vincent van Gogh: The Paris Wheat Field” in Nature as Muse: Inventing Impressionist Landscape.

Vincent van Gogh was born in the Netherlands in 1853 and lived there during his formational years as an artist. He arrived in Paris in spring 1886 at age 33. The self-taught painter had already made several attempts over the past years to systematically study art. Having tried his hand as an art dealer, a teacher, a preacher, a bookseller, a theology student, and a missionary, he had recently left Holland to attend the Antwerp Academy of Art, but had stayed only a few months. Now in Paris, he was determined to dive into the world of art for good. On his brother Theo’s advice, he intended to enter the studio of Fernand Cormon, connect with other painters, become familiar with the art movements of the time, and tap into the flourishing trade in art, because “one must be in the artists’ world.”

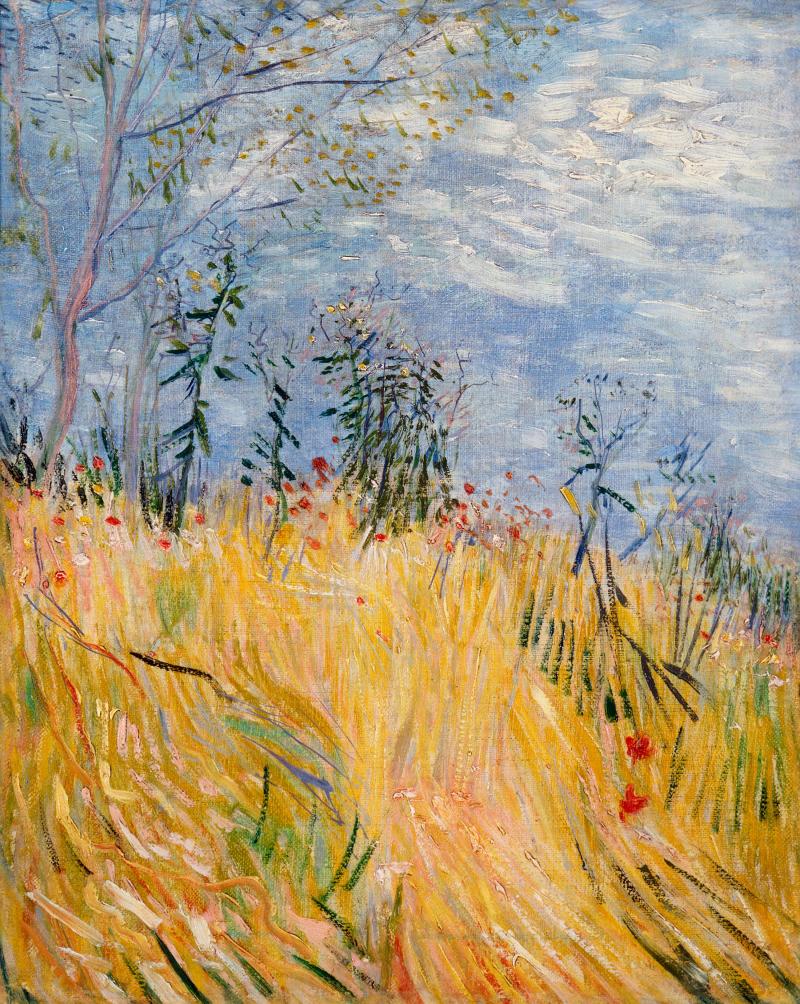

Edge of a Wheat Field with Poppies, painted in the summer of 1887, gives a sense of the many influences van Gogh was exposed to during his first year in the “hotbed of ideas” (as he called Paris in a letter to his sister).

The small painting captivates us with its bright contrast between the orange yellow of the field and the complementary radiant blue of the sky, the dark green of the new shoots coming up and the vivid vermillion of the poppies, sprinkled across the canvas in free dashes. The vertical space is evenly divided between earth and sky. The vantage point is surprisingly low to the ground; we look at the scene as though up a hill. This is not the vast expanse of field shown in a Caillebotte painting or van Gogh’s later landscapes, but a detail—a highly fragmented view. A slender poplar arcs along the left edge of the painting, and clusters of budding stalks seem to dance on the horizon line.

With no identifying urban features inside the frame, it is impossible to say whether van Gogh’s wheat field was located in Montmartre, where he was living at the time, or in the vicinity of Paris. While the city of one million inhabitants lay spread out at his feet on one side of the hill of Montmartre, the original rural aspect of the neighborhood was still visible on the other, close by his apartment. Montmartre had been incorporated into the city only a few years earlier, and the far side of the hill was still largely rural in character, complete with vegetable gardens, fields, and windmills, as well as a wide view over the open expanse of the Île de France. This area and the nearby village of Asnières, where he painted views of the Seine and of leisure life, provided van Gogh with many of his rural motifs during his two-year stay in Paris.

The upright format, relatively rare in landscape painting, and the unconventional perspective, which divides the surface of the painting evenly between sky and field, reveal van Gogh’s fascination with Japanese art and its influence on his work in Paris. The colored woodblock prints of artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige had already captured the interest of the Impressionists, strengthening their resolve to free painting from mere representation. Japonisme—enthusiasm for Japanese art and culture—reached its peak in Paris in the 1880s. Ever more dealers stocked woodblock prints, and even department stores sold them at affordable prices; upon his arrival, van Gogh was able to rapidly amass a considerable collection. He exhibited a selection of his prints at the Café Tambourin in March 1887. “The exhibition of Japanese prints that I had at the Tambourin had quite an influence on Anquetin and Bernard,” he later wrote to Theo.

Van Gogh, too, was under the spell, and that year he began to systematically incorporate Japanese motifs into his own work through copies and free interpretations of such prints. In doing so, he replaced the more subdued tonalities of the originals with bright colors intensified through complementary contrasts. Edge of a Wheat Field with Poppies, with its Asian-inspired asymmetrical composition and feather of a poplar tree, may be one of the earliest examples of how van Gogh carried the spatial considerations of Japanese prints into his own work.

While these prints may have been the impetus for the flat, dynamic compositions he created in Paris, van Gogh also looked to Japan as a model for his ideal of a painters colony, where artists could overcome envy and rivalry to work cooperatively. He believed he might find a version of this utopian Japan in the Midi region of southern France. After two years in Paris, van Gogh set out for Arles in spring 1888. He wrote to Theo: “Look, we love Japanese painting, we’ve experienced its influence—all the Impressionists have that in common—and we wouldn’t go to Japan, in other words, to what is the equivalent of Japan, the south? So I believe that the future of the new art still lies in the south after all.”

The ripe field under a cloudy summer sky was to become a dominant motif in van Gogh’s work during his years in the southern towns of Arles and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, and later in Auvers. The small Wheat Field from the environs of Paris is the very first rendering of this motif— an empty field under an open sky, without peasants or livestock. He reinterpreted the idea in a tremendous range of paintings, sounding out the limits of perspective, composition, and color. The field was an open, many-layered metaphor for van Gogh. In a letter to Theo and his wife, Johanna, shortly before his death, Vincent wrote of his pictures: “They’re immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness.”

This attempt to render the emotional inner life of the individual through art—a notion that would not even have occurred to the Impressionists—marks the transition from the positivistic stance of Impressionism to the absolute subjectivity of the Expressionists. A new era had begun.

You must be logged in to post a comment.