Farmacia della delegazione inglese aperta in via Tornabuoni nella prima meta’ dell’ ottocento da H. Roberts e C.

Farmacia della delegazione inglese aperta in via Tornabuoni nella prima meta’ dell’ ottocento da H. Roberts e C.

Quick as in an hour. I found this BBC documentary very enjoyable and informative and a good reminder of how the Renaissance developed under Medici patronage. (I found the tie-ins to art being the hot commodity it is in the modern world less interesting/persuasive). A great, quick visual trip to see the world created by the Medici clan.

One of my favorite places in Florence is the Palazzo Davanzati. One look at one of the rooms in the palazzo will show you why I love it. I visited it on my very first trip to Florence, almost 40 years ago. It hasn’t changed one bit, except maybe it is even better now with more didactic info available.

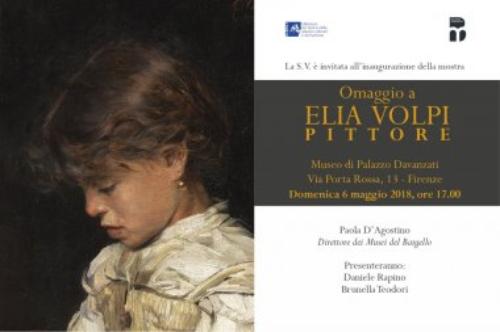

We have the art dealer, Elia Volpi (1858–1938), to thank for having saved the Palazzo as it appears today. In Florence, Volpi is known as the “father” of the Museum of the Old Florentine House in Palazzo Davanzati, as he was responsible for restoring the building and turning it into a private museum in 1910.

Now the museum, on via Porta Rossa, is opening its “Homage to Elia Volpi the Painter” exhibition, which offers the chance to discover a lesser-known side of the illustrious collector and antiquarian, that is, to see him as an artist.

Volpi trained at Florence’s Academy of Fine Arts. The current exhibition focuses on his training and the paintings he produced from the 1870s through the 1890s, with examples of his sketches and finished paintings, mostly in pristine condition. All of these works have been donated to the museum from private collections.

Volpi’s sketches are testament to his studies of the Italian Renaissance masters and, along with the male nudes, show off the early artistic skills of a young Volpi.

The paintings demonstrate his broad range; during the 1880s he explored church scenes before concentrating on the subjects and style of the Macchiaioli and more contemporary artists such as Francesco Gioli and Niccolò Cannicci.

The show also includes a multimedia section featuring a video that focuses on the artist’s personal life and a touch-screen panel with photographs that demonstrate the creation of the museum.

The exhibition is open from May 6 to August 5 in the Palazzo Davanzati Museum.

The source of this info comes from:

http://www.theflorentine.net/art-culture/2018/05/elia-volpi-exhibition-palazzo-davanzati/

Papal excess, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Stephen Colbert.

In its heyday, Bagni di Lucca, with its cool climate and great variety of hot springs had been a very fashionable European holiday resort and spa town. Beautiful elegant hotels had been built all around the spas. Villas, owned by heads of state and various ambassadors and dignitaries were crammed with antique furniture, musical instruments and rare books.

There were cultural centres, casinos, Anglican churches and cemeteries, restaurants and theatres. Famous poets, singers, playwrights, writers, actors and actresses used to flock there in the summer months. Presumably, many wars and marriages were arranged and important state decisions taken inside those thick stone walls, so far from indiscreet ears.

With the advent of fascism in Italy, renewed nationalism and World War Two, the “guests” of Bagni di Lucca suddenly became completely undesirable, and were later either deported or forced to flee.

Their properties were confiscated which meant that the local fascist bosses, for the most part rude uneducated thugs, suddenly had access to and became owners of luxurious properties full of rare works of art. There are tales of grand pianos being chopped up for firewood, rare books being transported to the local paper mills and being sold by the kilo, manuscripts being burnt on bonfires, and paintings being thrown out on to the grass where rain and sun eventually got the better of them.

Some of the villas miraculously passed into the hands of new owners. Deeds were drawn up, and illiterate mountain folk suddenly felt like princes and princesses. Some were used for more sinister purposes, housing torture and detention centres for political opponents, intellectuals and partisans or worse, boarding houses for Jewish and gypsy children before they left for their final destinations.

The grand rooms and theatres, which had housed great composers and musicians, were turned almost overnight into brothels or barracks for Mussolini’s troops.

At last! Many dignitaries thought that law and order has been restored. We are in charge again and those foreigners got what they deserved!

Of course, things didn’t quite turn out as expected. Italy did not get its empire, but instead a humiliating loss in which not only did it once again have to bow down to the overwhelming power of the Anglo-American armies, but it also had to sign really unfair future agreements, thus becoming a near slave to the foreign oil barons, military-industrial complexes, big Pharma religion and cars and motorways.

After the war there was no money for the upkeep and maintenance of the once magnificent hotels and spa complexes and anyway the whole of Italy was busy doing other things. People were emigrating in hordes, abandoning villages, hilltops and mountains for large industrial cities in the north, going to work in the booming car industries or in foreign cities.

The people were all working like busy bees for their new masters, building motorways and high rise blocks of flats, spraying clean fields, vineyards and fruit farms with toxic pesticides, getting rich and watching TV.

Bagni di Lucca became a ghost town. Gone were the shepherds and their flocks, the orderly rows of vegetables, the pigs, cows, geese and ducks, the large families and old traditions. Winters passed and vegetation covered the villages and country lanes. Vines grew over and smothered the beautiful old buildings until there was nothing left, except memories in books which no one ever opened.

Small factories sprang up in Bagni di Lucca: paper mills spewing out clouds of black smoke and colouring the rivers pink and blue, and the souvenir industry which exported plastic figurines to many parts of the world. The owners of these businesses became very wealthy and the only people left who had not emigrated elsewhere worked entirely for the “benefactors” who could therefore pay as little or as much as they liked, as people had no other alternative.

In the 1960s and 70s, people had started to talk about the possibility of starting up the tourist business once more but this was generally discouraged by the benefactors as it would have meant distraction for their workers. So by the time the international association arrived in town they were entering a world which might as well have been in a time warp.

Actually, as we later found out, they, being mostly highly intelligent and educated people, had vision and they had realised back then that it was time to flee the big cities before globalisation, the de-industrialisation of Italy, mass unemployment, climate change, wars for oil and water and social unrest hit us all. They were right about that, they just chose the wrong place.

Welcome to Tuscany.

Lord, Anna. Welcome to the Tuscan Dream: Italy’s Broken Heart (p. 63). Scribo Srl. Kindle Edition.

Diana Nixon in a pleated dance dress by Maggy Rouff.

Photo by Georges Saad, 1960

The 24th ARTIGIANATO E PALAZZO exhibition (Florence, Corsini Gardens, May 17-20, 2018) gets underway with the history of one of the leading examples of Made in Italy excellence, the “Mostra Principe” dedicated to the Richard Ginori porcelain Manufactory and fundraising for the reopening of the Doccia Museum, recently acquired by MiBACT (Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism).

“The hundreds of requests to take part that we have received this year represent an excellent sign of recovery in the artisan sector, because craftspeople are the lifeblood of Made in Italy,” said Giorgiana Corsini and Neri Torrigiani who, for over twenty-four years, have been involved in organizing the ARTIGIANATO E PALAZZO event and in promoting Italy’s artisan heritage.

During the four-day event in the Limonaia Piccola of the 17th-century Corsini Gardens (open to the public for this occasion), the Richard Ginori company will recreate various phases in the creative process through which, daily since 1735, it has produced unique porcelain pieces, with special live demonstrations to reveal to the public a story that has survived to the present day with a rich tradition of know-how, innovation and beauty.

For the first time, it will be possible to admire outside the plant in Sesto Fiorentino the Manufactory’s artisans at work in their various areas of expertise: from slip casting to decoration, evidence of a wealth of knowledge that has been handed down without interruption from older to younger generations of craftspeople.

For its part, the Doccia Museum will be the recipient of the major fundraising initiative, “ARTIGIANATO E PALAZZO FOR THE DOCCIA MUSEUM”that Giorgiana Corsini and Neri Torrigiani have decided to launch with this year’s event “so that the priceless collection of the Doccia Museum will once again be open to the public”. 8,000 porcelain, ceramic, majolica, terracotta and lead objects and over 13,000 drawings, engraved metal plates, chromolithograph stones, plaster molds and wax sculptures.

The project involves a series of initiatives that will involve the organizers, public and corporate sponsors of the 24th ARTIGIANATO E PALAZZO exhibition, the full proceeds of which will go to the Associazione Amici di Doccia:

If you are in Florence in the next 6 months, I recommend you pay a visit to Florence’s Rose Garden (Giardino delle rose), which is a garden park in the Oltrarno district of Florence, located between Viale Giuseppe Poggi, Via di San Salvatore al Monte and Via dei Bastioni and offers a commanding view of the city.

The garden is situated on the southern slopes of the Monte alle Croci, overlooking the Arno river and the historic district of Florence.

The Rose Garden was created by the Florentine architect Giuseppe Poggi in 1865, commissioned by the municipality of Florence to develop the left bank of the Arno River, when the capital of Italy was moved from Turin to Florence that year. Poggi’s contributions include both the Piazzale Michelangelo and the garden.

The Rose Garden is a terraced area of about 1 ha. Once part of the property of the Oratorian Fathers, the area was transformed into a garden by Attilio Pucci, who started the collection of roses.

Signa is a comune (municipality) in the Province of Florence in the Italian region Tuscany, located about 12 kilometres (7 mi) west of Florence. As of 1 July 2013, it had a population of 19571 and an area of 18.8 square kilometres (7.3 sq mi).[1]

The municipality of Signa contains the frazioni (subdivisions, mainly villages and hamlets) Colombaia, Lecore, Sant’Angelo a Lecore and San Mauro a Signa. Signa is a typical Tuscan town. On the day after Easter, there is an important religious festival in honour of the Beata Giovanna. There is a procession that parades in the streets of Signa, and many people wear old costumes.

In Giacomo Puccini‘s Gianni Schicchi, the “molini di Signa” (mills of Signa) are the most coveted by his relatives of Buoso Donati’s properties. The 1875 novel Signa by Ouida (Mary Louise Ramé) is set in Signa.

Opera fanatics may recall Signa’s role in the Giacomo Puccini-penned “Gianni Schicchi,” but Puccini superfans and Florence area residents aside, it remains relatively unknown.

Right at the junction of three key Tuscan rivers—the Arno, Bisenzio and Ombrone Pistoiese—it’s home to a longstanding craft tradition with inextricable ties to the land itself.

Dig into the territory and its top product with these tips.

The signature craft in town is undoubtedly the straw hat, known in Italian as the cappello di paglia and highlighted in the Domenico Michelacci Straw and Weaving Museum. The museum’s namesake, Domenico Michelacci, was an enterprising 18th century man who was among the first to depart from cultivating wheat strictly for dietary purposes: instead, he intentionally set his sights on straw to be used in weaving.

Michelacci worked specifically with grano marzuolo, set apart for its tiny grains and small ears. A watershed moment for the local economy, this change introduced by Michelacci ultimately led the Florentine area to become the West’s first area for high-quality straw hat production, piquing the attention of wealthy clients around the world.

Demands of clients have naturally shifted through the centuries, as have the fashions themselves, but the straw hat remains the icon of Signa. A visit to the museum will illustrate why: each room showcases important elements of this niche market and its role in local history.

Those most interested in the links to the land will enjoy perusing the different types of wheat on display, while the more aesthetically minded might prefer the plethora of hats spanning the early 20th century to the 1970s. An additional room focuses entirely on the various machines and tools used to manually work with straw (although this type of equipment is dispersed throughout the museum).

For more, see http://www.turismo.intoscana.it/allthingstuscany/aroundtuscany/florence-straw-hats/

You must be logged in to post a comment.