To me there are certain words that just seem poetic in and of themselves.

Indigo is one of them.

Indigo. I like the way it sounds.

I like to say it. Indigo.

I like the objects that are made using it.

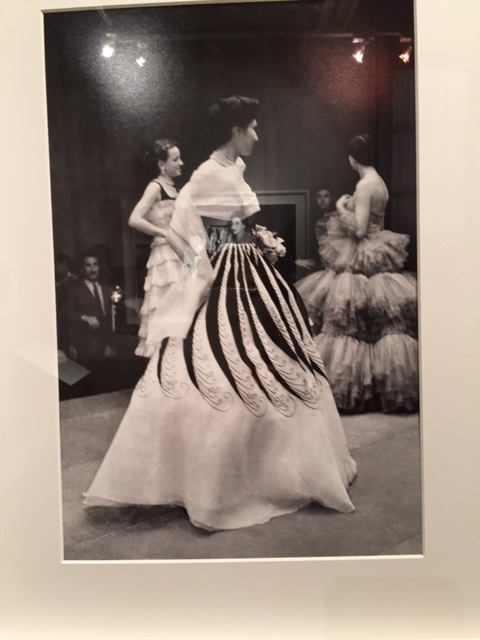

From the sublime:

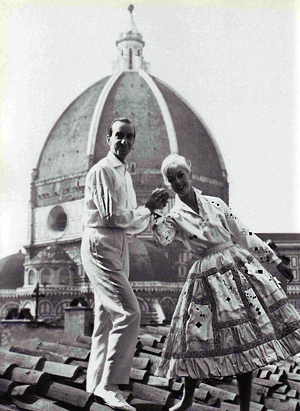

To the indispensable:

I love to think about where the word comes from and all the associations it carries. Once the dye was so valuable in the world market that it was known as “blue gold.”

indigo (n.)

17c. spelling change of indico (1550s), “blue powder obtained from certain plants and used as a dye,” from Spanish indico, Portuguese endego, and Dutch (via Portuguese) indigo, all from Latin indicum “indigo,” from Greek indikon “blue dye from India,” literally “Indian (substance),” neuter of indikos “Indian,” from India (see India).

Replaced Middle English ynde (late 13c., from Old French inde “indigo; blue, violet” (13c.), from Latin indicum). Earlier name in Mediterranean languages was annil, anil (see aniline). As “the color of indigo” from 1620s. As the name of the violet-blue color of the spectrum, 1704 (Newton).

http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=indigo

The color indigo was named after the indigo dye derived from the plant Indigofera tinctoria and related species. Blue dye was hard to achieve. A variety of plants have provided indigo throughout history, but most natural indigo was obtained from those in the genus Indigofera, which are native to the tropics. The primary commercial indigo species in Asia was true indigo (Indigofera tinctoria, also known as I. sumatrana).

A common alternative source of the dye is from the plant Strobilanthes cusia, grown in the relatively colder subtropical locations such as Japan’s Ryukyu Islands and Taiwan. In Central and South America, the two species grown are I. suffruticosa (añil) and dyer’s knotweed (Polygonum tinctorum), although the Indigofera species yield more dye.

India is believed to be the oldest center of indigo dyeing, both in terms of production and processing. The I. tincture species was domesticated in India. It was a primary supplier to the rest of the world of indigo dye.

The dye was in Europe as early as the Greco-Roman era, where it was valued as a luxury product. The Romans used indigo as a pigment for painting and for medicinal and cosmetic purposes. The extravagant item was imported into the Mediterranean lands from India by Arab merchants.

Indigo remained a rare commodity in Europe throughout the Middle Ages. A chemically identical dye derived from the woad plant (Isatis tinctoria), was used instead. Woad was replaced when true indigo became available through trade routes.

In the late 15th century, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama discovered a sea route to India.

This led to the establishment of direct trade with India, the Spice Islands, China, and Japan. Importers could now avoid the heavy duties imposed by Persian, Levantine, and Greek middlemen and the lengthy and dangerous land routes which had previously been used. Consequently, the importation and use of indigo in Europe rose significantly.

Much European indigo from Asia arrived through ports in Portugal, the Netherlands, and England.

Spain imported the dye from its colonies in South America.

Many indigo plantations were established by European powers in tropical climates; it was also a major crop in Jamaica and South Carolina, with much or all of the labor performed by enslaved Africans and African Americans.

Indigo plantations also thrived in the Virgin Islands.

However, France and Germany outlawed imported indigo in the 16th century to protect the local woad dye industry.

So valuable was indigo as a trading commodity, it was often referred to as blue gold.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indigo_dye

Indigo is among the oldest dyes to be used for textile dyeing and printing. Many Asian countries, such as India, China, Japan, and Southeast Asian nations have used indigo as a dye (particularly silk dye) for centuries. In Japan, indigo became especially important in the Edo period, when it was forbidden to use silk, so the Japanese began to import and plant cotton. It was difficult to dye the cotton fiber except with indigo. Even today indigo is very much appreciated as a color for the summer Kimono Yukata, as this traditional clothing recalls nature and the blue sea.

The dye was also known to ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Britain, Mesoamerica, Peru, Iran, and Africa.

The association of India with indigo is reflected in the Greek word for the ‘dye’, which was indikon (ινδικόν). The Romans used the term indicum, which passed into Italian dialect and eventually into English as the word indigo. El Salvador has lately been the biggest producer of indigo.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indigo

The first known recorded use of indigo as a color name in English was in 1289.

Historically,blue dyes were rare and hard to achieve, so indigo, a natural dye extracted from plants, was important economically. A large percentage of indigo dye produced today – several thousand tons each year – is synthetic. It is the blue often associated with blue jeans.

The primary use for indigo today is as a dye for cotton yarn, which is mainly for the production of denim cloth for blue jeans. On average, a pair of blue jean trousers requires 3–12 g of indigo. Small amounts are used for dyeing wool and silk.

Indigo carmine, or indigo, is an indigo derivative which is also used as a colorant. About 20 million kg are produced annually, again mainly for blue jeans.[1] It is also used as a food colorant, and is listed in the United States as FD&C Blue No. 2.

In 1675 Newton revised his account of the colors in a rainbow, adding the color of indigo which he located between the lines of blue and violet.

Newton had originally identified five colors, but enlarged his codification to seven in his revised account of the rainbow in Lectiones Opticae.

Indigo, a color in the rainbow.

Indigo

You must be logged in to post a comment.