France, the French, Paria

The birthplace of the Gothic style: La Basilique Royale de Saint-Denis

La Basilique Royale de Saint-Denis is not only the first true example of the Gothic style of architecture, but also the burial place for French royalty. It would be an understatement to state that it is a major church in Christendom.

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (French: La Basilique royale de Saint-Denis, or simply Basilique Saint-Denis) is a large medieval abbey church in the city of Saint-Denis, now a northern suburb of Paris. The building is of singular importance historically and architecturally as its choir, completed in 1144, shows the first use of all of the elements of Gothic architecture. Watch this brief Khan Academy video to get up to speed on Gothic.

Saint Denis was the patron saint of France and became the first bishop of Paris. He was decapitated on the hill of Montmartre in the mid-third century with two of his followers, and is said to have subsequently carried his head to the site of this current church, indicating where he wanted to be buried. A martyrium was erected on the site of his grave, which became a famous place of pilgrimage during the fifth and sixth centuries.

The site originated as a Gallo-Roman cemetery in late Roman times. The archeological remains still lie beneath the cathedral; the people buried there seem to have had a faith that was a mix of Christian and pre-Christian beliefs and practices.

Around 475 St. Genevieve purchased some land and built Saint-Denys de la Chapelle. In 636 on the orders of Dagobert I the relics of Saint Denis, the patron saint of France, were reinterred in the basilica.

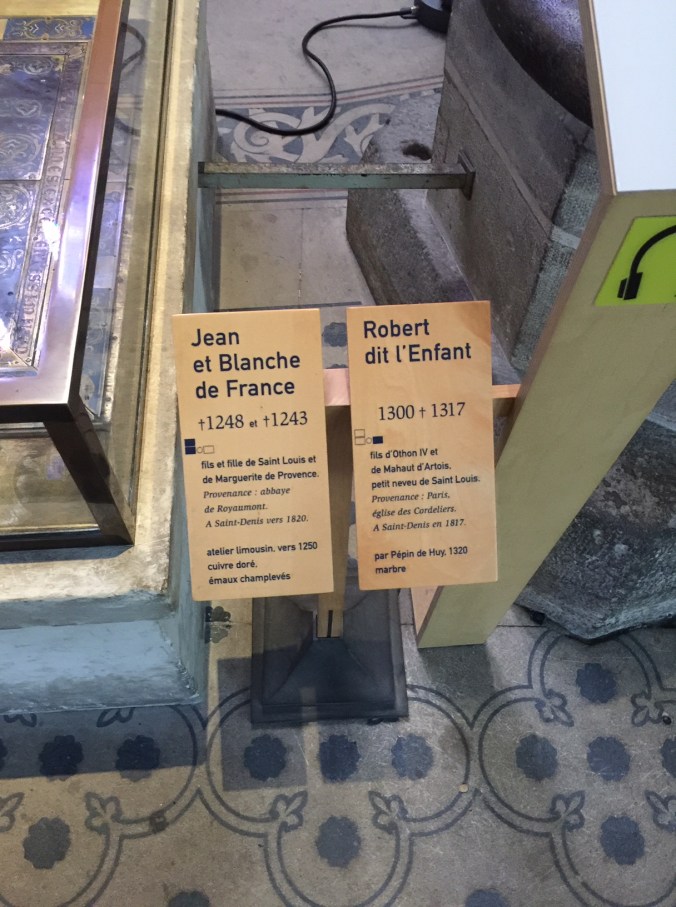

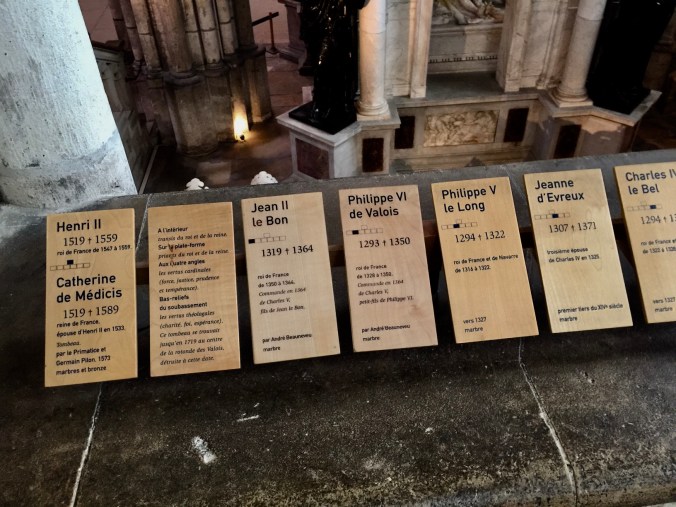

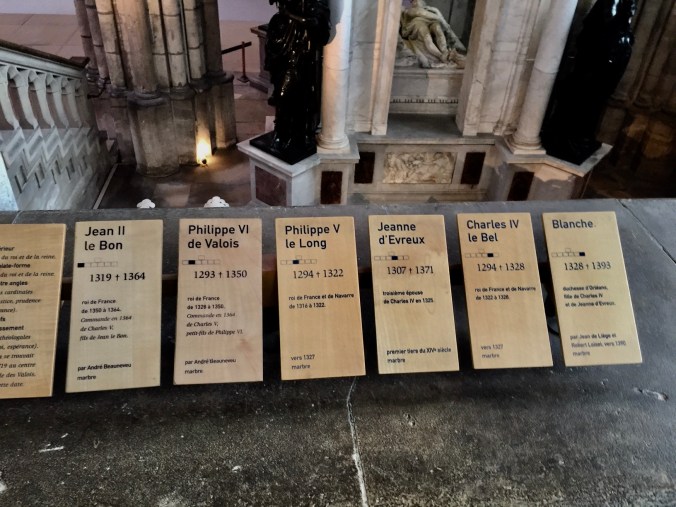

The basilica became a place of pilgrimage and the burial place of the French kings and queens, with nearly every king from the 10th to the 18th centuries buried there. Moreover, there were many royal tombs from previous centuries.

St. Denis was not used for the coronations of kings, that function being reserved for the Cathedral of Reims; however, French Queens were commonly crowned there. “Saint-Denis” soon became the abbey church of a growing monastic complex.

All but three of the monarchs of France from the 10th century until 1789 have their remains here. Some monarchs, like Clovis I (465–511), were not originally buried at this site. The remains of Clovis I were exhumed from the despoiled Abbey of St Genevieve which he founded.

In the 12th century, the Abbot Suger rebuilt portions of the abbey church using innovative structural and decorative features. In doing so, he is said to have created the first truly Gothic building. The basilica’s 13th-century nave is the prototype for the Rayonnant Gothic style, and provided an architectural model for many medieval cathedrals and abbeys of northern France, Germany, England and many other countries.

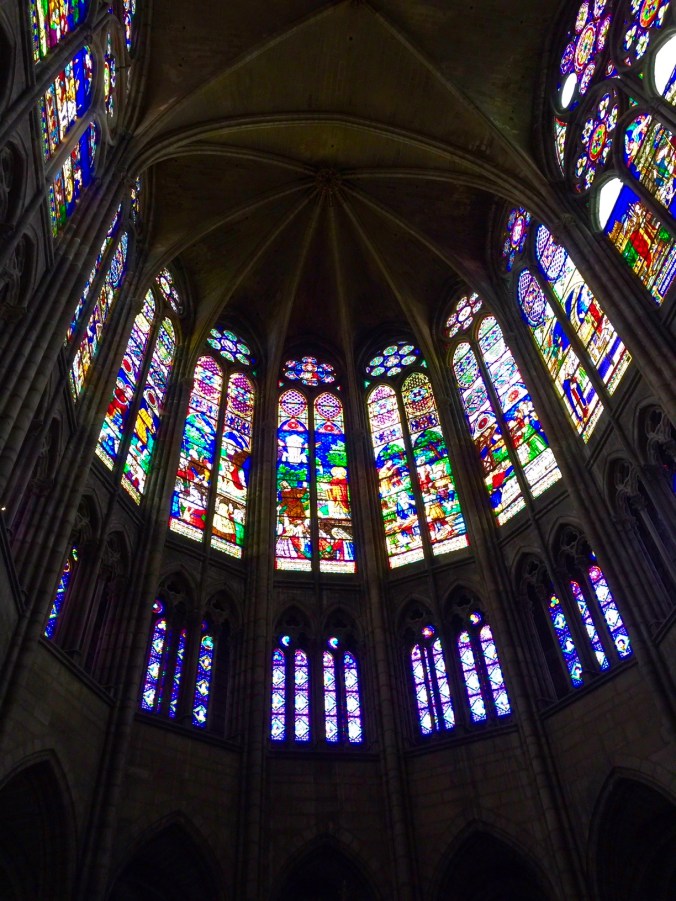

Above: the Rayonnant Gothic choir of St Denis.

Dagobert, the king of the Franks, reigned from 628 to 637, and he refounded the church as the Abbey of Saint Denis, a Benedictine monastery. Dagobert commissioned a new shrine to house the Saint Denis’s remains, which was created by his chief councillor, Eligius, a goldsmith by training.

King Dagobert’s own tomb in St. Denis below:

Above and below: the tomb of King Dagobert

When Abbot Suger was modifying the church, the façade was also redesigned and included tall, thin statues of Old Testament prophets and kings attached to columns (known as “jamb figures”) flanking the portals.

These jamb statues were an attractive addition to the Gothic façade, and were subsequently used at the cathedrals of Paris and Chartres, constructed a few years later, and became a feature of almost every Gothic portal thereafter.

Above the doorways, the central tympanum was carved with Christ in Majesty, displaying his wounds while the dead emerge from their tombs below. Scenes from the martyrdom of St. Denis were carved above the south (right hand) portal, while above the north portal was a mosaic (now lost), even though this was already retardataire, or, as Suger put it: “contrary to the modern custom.”

The French Revolution, havoc wreaked:

Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People.

Because of the church’s connections to the French monarchy and proximity to Paris, the abbey of Saint-Denis was a prime target of revolutionary vandalism. All of the medieval monastic buildings were demolished in 1792 and, unfortunately, the facade of the church suffered much mutilation at the hands of the revolutionaries. They mistakenly believed that the jamb statues depicted the kings of France. In this mistake, they battered the Gothic statuary, leaving little of the exterior’s decorative program intact.

Fortunately, especially for the study of the history of art, we have a record of how the jamb sculptures appeared in Montfaucon’s drawings.

The portal tympana sculpture was also defaced.

The tombs and effigies were obviously at risk during this chaotic time and so they were wisely relocated, by calmer minds than those of the pesky revolutionaries, to the Musée des Monuments Français by Alexandre Lenoir in 1798.

For a relatively brief period, the relics of St-Denis were transferred to the parish church of the town in 1795; they were returned to the abbey in 1819.

Of the original sculpture, very little remains, most of what is now visible being the result of rather clumsy restoration work in 1839. Some fragments of the original sculptures survive in the collection of the Musée de Cluny in Paris.

Although the revolutionaries left the church itself standing, it was deconsecrated, its treasury confiscated and its reliquaries and liturgical furniture melted down for their metallic value (although some objects, including a chalice and aquamanile donated to the abbey in Suger’s time, were successfully hidden and survive to this day) and the remaining royal tombs desecrated.

The church was reconsecrated (reopened) by Napoléon in 1806 and the tomb sculptures returned to Saint-Denis when Lenoir’s Musée des Monuments Français was closed after the restoration of the monarchy.

The royal remains, however, were left in the mass graves to which they had been placed in 1798.

Below is the Bourbon crypt, or the Memorial to King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette, sculptures (1830) by Edme Gaulle and Pierre Petitot

Under the direction of architect Viollet-le-Duc, famous for his work on Notre-Dame de Paris, church monuments that had been taken to the Museum of French Monuments were returned to the church. The corpse of King Louis VII, who had been buried at Barbeau Abbey and whose tomb had not been touched by the revolutionaries, was brought to Saint-Denis and buried in the crypt. In 2004, the mummified heart of the Dauphin, the boy who would have been Louis XVII, was sealed into the wall of the crypt.

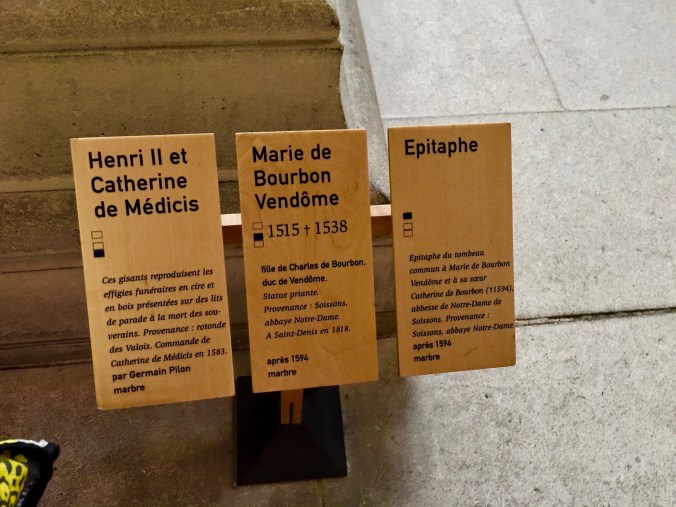

The abbey church contains some fine examples of cadaver tombs. The effigies of many of the kings and queens are on their tombs, but their bodies were removed during the French Revolution. The ancient monarchs were removed in August 1793 to celebrate the revolutionary Festival of Reunion, then the Bourbon and Valois monarchs were removed to celebrate the execution of Marie Antoinette in October 1793. The bodies were dumped into three trenches and covered with lime to destroy them.

Archaeologist Alexandre Lenoir saved many of the monuments by claiming them as artworks for his Museum of French Monuments. The bodies of several Plantagenet monarchs of England were likewise removed from Fontevraud Abbey during the French Revolution.

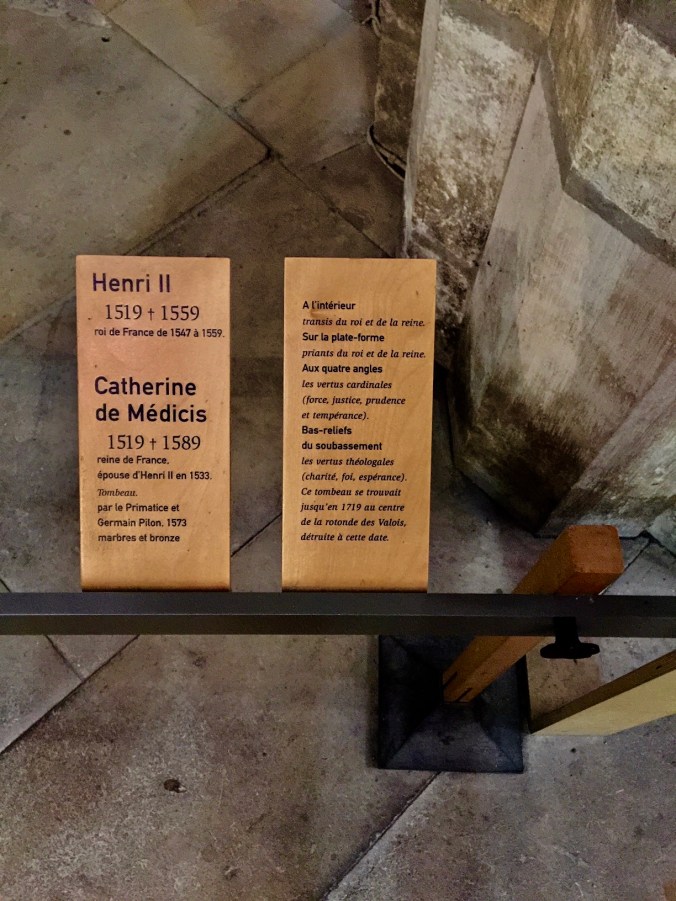

At top are Effigies on the tomb of Henry II and Catherine de’ Medici, carved by Germain Pilon.

The bodies of the beheaded King Louis XVI, his wife Marie Antoinette of Austria, and his sister Madame Élisabeth were not initially buried in Saint-Denis, but rather in the churchyard of the Madeleine, where they were covered with quicklime.

The body of the Dauphin, who died of illness and neglect at the hands of his revolutionary captors, was buried in an unmarked grave in a Parisian churchyard near the Temple.

In 1817, the restored Bourbons ordered the mass graves to be opened, but only portions of three bodies remained intact. The remaining bones from 158 bodies were collected into an ossuary in the crypt of the church, behind marble plates bearing their names.

During the restoration the Bourbons ordered search for the corpses of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, but only a few bones were found that were presumably the king’s and a clump of greyish matter containing a lady’s garter, were found on 21 January 1815. They were brought to Saint-Denis and buried in the new Bourbon crypt.

King Louis XVIII, upon his death in 1824, was buried in the center of the crypt, near the graves of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The coffins of royal family members who died between 1815 and 1830 were also placed in the vaults.

The church, including the architectural sculpture and stained glass windows (of which very little medieval glass survives) was heavily restored in the mid-nineteenth century by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, the same architect responsible for the restoration of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame. Under Viollet-le-Duc’s direction, church monuments that had been taken to the Museum of French Monuments were returned to the church.

The present location of the tomb effigies does not correspond to their medieval locations.

The corpse of King Louis VII, who had been buried at Barbeau Abbey and whose tomb had not been touched by the revolutionaries, was brought to Saint-Denis and buried in the crypt. In 2004, the mummified heart of the Dauphin, the boy who would have been Louis XVII, was sealed into the wall of the crypt.

London’s Courtauld Institute, on exhibit in Paris

I was so fortunate when I visited the Fondation Louis Vuitton recently that an excellent exhibition from London was on view. I couldn’t help myself: it was so refreshing to see “modern art” in Paris after non stop Renaissance art in Florence all of the time. Ha! Never thought I’d live to say those words!

La Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris

Oops! I fell way behind on posting my Paris adventures! Let me start again now!

The Louis Vuitton Foundation, in French: La Fondation Louis Vuitton, has its home in a spectacular building in the 16th arrondissement, Paris, France. This building serves as an art museum and cultural center, sponsored by the group LVMH and its subsidiaries. It is run as a legally separate, nonprofit entity as part of LVMH’s promotion of art and culture. And isn’t the world lucky for all of that!

In 2001, Bernard Arnault, the Chairman of LVMH, met world-renowned architect, Frank Gehry, and told him of plans for a new building for the Louis Vuitton Foundation for Creation on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne. Suzanne Pagé, then director of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, was named the foundation’s artistic director in charge of developing the museum’s program.

Not everything went according to plan.

The city of Paris, which owns the park, granted a building permit in 2007. In 2011, an association for the safeguard of the Bois de Boulogne won a court battle, as the judge ruled the centre had been built too close to a tiny asphalt road deemed a public right of way.

Opponents to the site had also complained that a new building would disrupt the verdant peace of the historic park.

The city appealed the court decision and eventually a special law was passed by the Assemblée Nationale that the Fondation was in the national interest and “a major work of art for the whole world,” which allowed it to proceed.

I believe I was very fortunate to visit La Fondation on a clear, sunny day (because, believe me…some of the days were cold and cloudy during my visit), and because I was able to see the exhibit from London’s Courtauld Institute. I’ll post about the exhibit itself another day. My focus today is on the incredible building itself.

The Fondation Louis Vuitton is located on prime property in Paris, next to the Jardin d’Acclimatation in the Bois de Boulogne, the famous park on the west side of the Capitol city. Napoleon III and the Empress Eugénie opened the Jardin d’Acclimatation in October 1860. They thus provided the Paris they were intent on rebuilding with a landscaped park designed in accordance with the model of English gardens that they so admired.

The building soars!

And it frames the sky and the park and city beyond it:

The following paragraphs are taken from the Fondation’s website:

“From an initial sketch drawn on a blank page in a notebook, to the transparent cloud sitting at the edge of the Jardin d’Acclimatation in the Bois de Boulogne, Frank Gehry constantly sought to “design, in Paris, a magnificent vessel symbolising the cultural calling of France.”

:A creator of dreams, he has designed a unique, emblematic and bold building.

Respectful of a history rooted in French culture of the 19th century, Frank Gehry dared to use technological achievements of the 21st century, opening the way for pioneering innovation.”

“Frank Gehry retained from the 19th century the transparent lightness of glass walls and the taste for walks punctuated by surprises.

“His architecture combines a traditional “art de vivre”, visionary daring and the innovation offered by modern technology.

“From the invention of glass curved to the nearest millimetre for the 3,600 panels that form the Fondation’s twelve sails to the 19,000 panels of Ductal (fibre-reinforced concrete), each one unique, that give the iceberg its immaculate whiteness, and not forgetting a totally new design process, each stage of construction pushed back the boundaries of conventional architecture to create a unique building that is the realisation of a dream.”

“This great architectural exploit has already taken its place among the iconic works of 21st-century architecture. Frank Gehry’s building, which reveals forms never previously imagined until today, is the reflection of the unique, creative and innovative project that is the Fondation Louis Vuitton.

“To produce his first sketches, Frank Gehry took his inspiration from the lightness of late 19th-century glass and garden architecture. The architect then produced numerous models in wood, plastic and aluminium, playing with the lines and shapes, investing his future building with a certain sense of movement. The choice of materials became self-evident: an envelope of glass would cover the body of the building, an assembly of blocks referred to as the “iceberg”, and would give it its volume and its vitality.

“Placed in a basin specially created for the purpose, the building fits easily into the natural environment, between woods and garden, while at the same time playing with light and mirror effects. The final model was then scanned to provide the digital model for the project.”

Paris in 1900

A modern Parisian fountain: a new take on an old form

One of the many delights of Paris is the Fondation Louis-Vuitton pour la création with its exhibition spaces and fountain. I’ll be posting soon about the building itself, by Frank Gehry. But for now, I want to focus only on the water.

The water is also inside the building, sort of. The sound of the water from inside the building reminds me of Frank Lloyd Wright’s house in Pennsylvania: Falling Water.

Medici Fountain, Luxembourg Garden, Paris and Marie de’ Medici

The artistic interchanges between Italy and France form a fascinating story. No where are they better expressed, at least to my mind, than in the Medici Fountain, commissioned by Marie de’ Medici at in the Luxembourg Garden in 1630. The fountain has a 3-part history: 1. its original construction; 2. its restoration by Napoleon; and 3. the relocation and additions of sculpture in 1866.

Marie de’ Medici was the widow of France’s King Henry IV and the regent of King Louis XIII of France.

The fountain in the Luxembourg garden was designed by Tommaso Francini, a Florentine fountain maker and hydraulic engineer who was brought from Florence to France by King Henry IV. The fabulous fountain was constructed in the form of a grotto, a popular feature of the Italian Renaissance garden.

The French queen was born as Maria at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, Italy. She was the sixth daughter of Francesco I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Archduchess Joanna of Austria. Marie was not a male-line descendant of Lorenzo the Magnificent but from Lorenzo the Elder, a branch of the Medici family sometimes referred to as the ‘cadet’ branch. She did descend from Lorenzo in the female-line however, through his daughter Lucrezia de’ Medici. She was also a Habsburg through her mother, who was a direct descendant of Joanna of Castile and Philip I of Castile.

Although Marie was one of seven children, only she and her sister Eleonora survived to adulthood.

She married Henry IV of France in October 1600 following the annulment of his marriage to Margaret of Valois. The wedding ceremony was held in Florence, and was celebrated by four thousand guests with lavish entertainment, including examples of the newly invented musical genre of opera, such as Jacopo Peri’s Euridice. Henry did not attend the ceremony, and the two were therefore married by proxy. Marie brought as part of her dowry 600,000 crowns. Her eldest son, the future King Louis XIII, was born at Fontainebleau the following year.

Her husband was almost 47 at the time of the marriage and had a long succession of mistresses. Dynastic considerations required him to take a second wife, his first spouse Margaret of Valois never having produced children by Henry or by her lovers. Henry chose Marie de’ Medici because Henry owed the bride’s father, Francesco de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who had helped support his war effort, a whopping 1,174,000 écus and this was the only means Henry could find to pay back the debt.

The marriage was successful in producing children, but it was not a happy one. The queen feuded with Henry’s mistresses in language that shocked French courtiers. She quarreled mostly with her husband’s leading mistress, Catherine Henriette de Balzac d’Entragues, whom he had promised he would marry following the death of his former “official mistress”, Gabrielle d’Estrées. When he failed to do so, and instead married Marie, the result was constant bickering and political intrigues behind the scenes.

Catherine referred to Maria as “the fat banker’s daughter”; Henry used Maria for breeding purposes exactly as Henry II had treated Catherine de’ Medici. Although the king could have easily banished his mistress, supporting his queen, he never did so. She, in turn, showed great sympathy and support to her husband’s banished ex-wife Marguerite de Valois, prompting Henry to allow her back into the realm.

Marie was crowned Queen of France on 13 May 1610, a day before her husband’s death. Hours after Henry’s assassination, she was confirmed as regent by the Parliament of Paris. She immediately banished his mistress, Catherine Henriette de Balzac, from the court.

The construction and furnishing of the Palais du Luxembourg, which she referred to as her “Palais Médicis”, formed her major artistic project during her regency. The site was purchased in 1612 and construction began in 1615, to designs of Salomon de Brosse.

It was well known that Henry of Navarre (her husband) was not wealthy. She brought her own fortune from Florence to finance various construction projects in France. But more importantly, she contributed to the financing of several expeditions including Samuel de Champlain’s to North America, which saw France lay claim to Canada.

In 1612 Marie de’ Medici had 2,000 elm trees planted, and directed a series of gardeners, most notably Tommaso Francini, to build a park in the style she had known as a child in Florence.

Francini planned two terraces with balustrades and parterres laid out along the axis of the chateau, aligned around a circular basin. He also built the Medici Fountain to the east of the palace as a nympheum, an artificial grotto and fountain, without its present pond and statuary.

The Medici Fountain fell into ruins during the 18th century, but in 1811, at the command of Napoleon Bonaparte, the fountain was restored by Jean Chalgrin, the architect of the Arc de Triomphe.

In 1864-66, the fountain was moved to its present location, centered on the east front of the Palais du Luxembourg. The long basin of water was built and flanked by plane trees, and the sculptures of the giant Polyphemus surprising the lovers Acis and Galatea, by French classical sculptor Auguste Ottin, were added to the grotto’s rockwork.

Pretty pink Parisian peonies

Atelier des Lumières, Paris

Paris has been coming at me so fast and furiously for the past 10 days or so that I am struggling to stay on top of my thousands of photos and stories as I engage with this incredible city. Yesterday I attended a showing at the Atleliers des Luminieres, Fonderie du Chemin-Vert. Wow. Pretty cool!

So, have you heard about these immersive art and music extravaganzas? The one in Paris uses the same format already devised and shown in the Carrières de Lumières at the old quarries in Les Baux de Provence. (In 2011, the town of Les Baux-de-Provence entrusted Culturespaces with the management of its famous quarry as part of a public services contract. Named “Carrières de Lumières,” it is a fantastic laboratory of creativity: Culturespaces has developed the innovative concept known as AMIEX® [Art & Music Immersive Experience]). There are similar shows done in an old church in Florence, Italy as well.

The digital exhibitions are made up of thousands of images of digitized works of art, broadcast in very high resolution via fiber optics, and set in motion to the rhythm of music. It takes 140 projectors and a careful orchestration of sound to create an exhibition.

Not everyone in the art world has welcomed this sort of “millennial” approach to the arts; but Culturespaces argue that the target audience for these immersive exhibitions is not connoisseurs of the art world, but rather families and young people who are not used to visiting museums. The Atelier’s first year statistics seem to show the exhibitions are reaching their target: in first year of operation, the Atelier des Lumières welcomed more than one million visitors, 12% of whom were under 25 years of age.

Giverny in video

You must be logged in to post a comment.