History

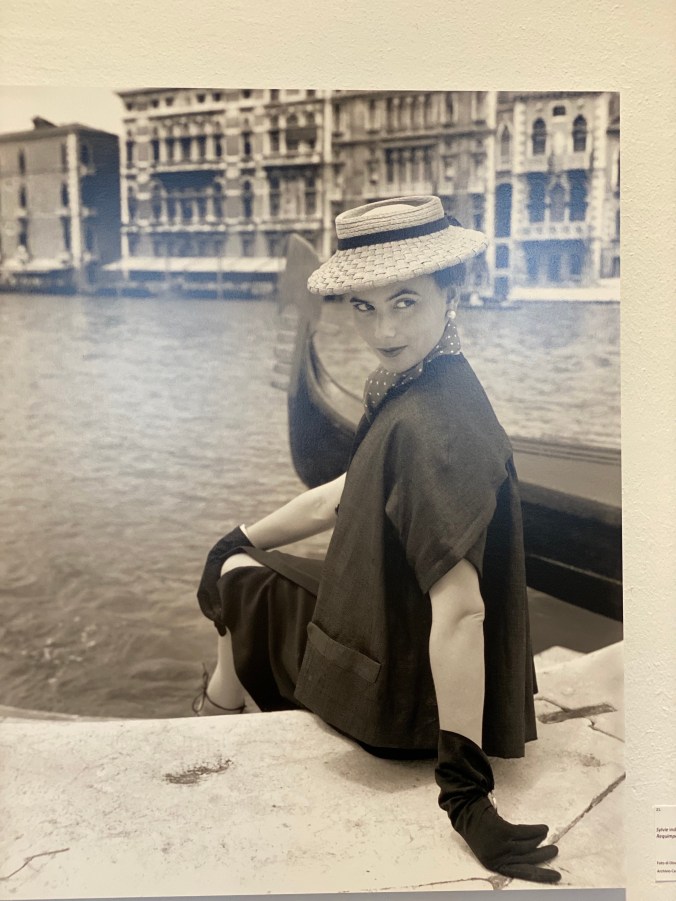

Christian Dior in Venice; current photography exhibit at Villa Pisani

This lovely little exhibition, entitled Timeless Elegance, Dior in Venice in the Cameraphoto Archives, is currently on display at Villa Pisani, in Stra, on the Brenta Canal in the Veneto. I enjoyed seeing it very much.

From the website of the Villa:

1951 was a magical year for Venice. Some of the most intriguing views of the city co-starred in the campaign that publicised the creations of the couturier who was capturing all the world’s headlines at the time: Christian Dior.

On 3 September of that same year, Palazzo Labia hosted the “Ball of the Century”: the Bal Oriental, organised by Don Carlos de Beistegui y de Yturbe, attracted around a thousand glittering jetsetters from all five continents. This masked ball saw Dior, Dalí, a very young Cardin, Nina Ricci and others engaged as creators of costumes for the illustrious guests, in an event that made the splendour of eighteenth-century Venice reverberate around the world.

Silent witnesses of both of these events were the photographers of Cameraphoto, the photography agency founded in 1946 by Dino Jarach, who covered and recorded everything special that happened in Venice and beyond during those years.

We have Vittorio Pavan, the current conservator of the imposing Cameraphoto Archives (the historical section alone has more than 300,000 negatives on file) and Daniele Ferrara, Director of the Veneto Museums Hub, to thank for the project to show the photographs of those two historical events to the general public. The location chosen for them to re-emerge into the light of day is one of extraordinary significance: Villa Nazionale Pisani in Stra is the Queen of the Villas of the Veneto and it is no coincidence that it is adorned with marvellous frescoes by Giambattista Tiepolo, the same artist whose work also gazed down on the unforgettable masked ball in 1951 from the ceilings of Palazzo Labia.

For this exhibition, Pavan has chosen 40 photographs of the collection shown in Venice by Christian Dior.

In those days, every fashion show would present just under 200 models, calculated carefully to achieve the right balance between items that would be easy to wear and others that made more of a statement. Dior was the undisputed master of fashion in those post-war years. The whole world looked forward to his collections and discussed them hotly. No fewer than 25,000 people are estimated to have crossed the Atlantic every year, just to see (and to buy) his collections. Every time he changed a line (and every new season brought such a change), it was accepted with both enthusiasm and ferocious criticism: the former from his clan of admirers, the latter from those who opposed him.

In any case, no woman who aspired to keep abreast of fashion could afford to ignore the dictates issued by the couturier from his Parisian maison in Avenue Montaigne, where he already employed a staff of more than one thousand, despite having being established only five years before. Dior’s New look evolved with every passing season.

In 1950, he introduced the Vertical Line, in 1951 – as the photographs on show in Villa Pisani illustrate – no woman could avoid wearing his Oval Look: rounded shoulders and raglan sleeves, the fabrics modelled until they clung like a second skin. The essential accessory was of course the hat, for which Dior that year drew his inspiration from the kind traditionally worn by Chinese coolies.

For that autumn, though, he created the Princess line, which gave the illusion of extending below the breast.

In the breathtaking photographs from the Cameraphoto Archives, beautiful Dior-clad models perform a virtual duet with Venice, whose canals, churches and palaces are never a mere backdrop, but co-stars on a par with the great designer’s creations.

The second nucleus of this fascinating exhibition is devoted to the Grand Ball at Palazzo Labia, possibly the most glittering social event of the century.

All the bel monde flocked to Venice on that legendary 3 September. Don Carlos, popularly known as the Count of Monte Cristo, sent personal invitations to a thousand people. Dior, together with a veritable army of young tailors and accompanied by Dalí, was engaged to create the most alluring costumes, all designed to refer to the eighteenth century when Goldoni and Casanova lived here. There were costumes for men and women, but also for the greyhounds and other dogs that often accompanied their owners.

The torches that on that legendary evening illuminated the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, several Grandees of Spain, the Aga Khan, King Farouk of Egypt, Winston Churchill, many crowned heads, princes and princesses, a host of millionaires, such artists as Fabrizio Clerici and Leonor Fini, fashion designers of the calibre of Balenciaga and Elsa Schiapparelli and leading jetsetters Barbara Hutton, Lady Diana Cooper, Orson Welles, Daisy Fellowes, Cecil Beaton (whose photographs, published in Life magazine, gave the world something to dream about), the Polignacs and the Rothschilds.

Welcoming them in the midst of clouds of ballerinas and harlequins was the master of the house and host, who dominated the scene as he promenaded back and forth dressed as the Sun King on a 40 cm high platform. The heir of an immense fortune created in Mexico, Don Carlos spent some of his time living in Paris, where he owned a house designed by Le Corbusier and decorated by Salvador Dalí, and the rest at a chateau in the country. He had bought Palazzo Labia and restored it and was now offering it to his friends.

The aim of this exhibition is therefore to contribute to improving the appreciation and value of the Cameraphoto photography archives, which have been declared to be of exceptional cultural interest by the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, since they constitute an inestimable legacy for the wealth and variety of images.

It was with this in mind that the curators chose this nucleus of photographs depicting the clothing designed by one of the most ingenious and iconic fashion designers in history, who in his turn, through his creations, enabled a spotlight to be focused on a tiny fragment of the more than one thousand years of history of the city of Venice, helping us reconstruct the collective memory on which our present day is based.

Curated by Vittorio Pavan and Luca Del Prete, the exhibition is organised by the Veneto Museums Hub e Munus.

Villa Pisani: Cruising the Brenta Canal from Padua to Venice, part 2

I recently posted about this day-long cruise here (here, here and here) and now I pick up where I left off. Our first stop on the cruise after leaving Padua was in Stra at Villa Pisani. This incredible villa is now a state museum and very much work a visit. It was built by a very popular Venetian Doge.

The facade of the Villa is decorated with enormous statues and the interior was painted by some of the greatest artists of the 18th century.

Villa Pisani at Stra refers is a monumental, late-Baroque rural palace located along the Brenta Canal (Riviera del Brenta) at Via Doge Pisani 7 near the town of Stra, on the mainland of the Veneto, northern Italy. This villa is one of the largest examples of Villa Veneta located in the Riviera del Brenta, the canal linking Venice to Padua. It is to be noted that the patrician Pisani family of Venice commissioned a number of villas, also known as Villa Pisani across the Venetian mainland. The villa and gardens now operate as a national museum, and the site sponsors art exhibitions.

Construction of this palace began in the early 18th century for Alvise Pisani, the most prominent member of the Pisani family, who was appointed doge in 1735.

The initial models of the palace by Paduan architect Girolamo Frigimelica still exist, but the design of the main building was ultimately completed by Francesco Maria Preti. When it was completed, the building had 114 rooms, in honor of its owner, the 114th Doge of Venice Alvise Pisani.

In 1807 it was bought by Napoleon from the Pisani Family, now in poverty due to great losses in gambling. In 1814 the building became the property of the House of Habsburg who transformed the villa into a place of vacation for the European aristocracy of that period. In 1934 it was partially restored to host the first meeting of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, after the riots in Austria.

From the outside, the facade of the oversized palace appears to command the site, facing the Brenta River some 30 kilometers from Venice. The villa is of many villas along the canal, which the Venetian noble families and merchants started to build as early as the 15th century. The broad façade is topped with statuary, and presents an exuberantly decorated center entrance with monumental columns shouldered by caryatids. It shelters a large complex with two inner courts and acres of gardens, stables, and a garden maze.

The largest room is the ballroom, where the 18th-century painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo frescoed the two-story ceiling with a massive allegorical depiction of the Apotheosis or Glory of the Pisani family (painted 1760–1762).[2] Tiepolo’s son Gian Domenico Tiepolo, Crostato, Jacopo Guarana, Jacopo Amigoni, P.A. Novelli, and Gaspare Diziani also completed frescoes for various rooms in the villa. Another room of importance in the villa is now known as the “Napoleon Room” (after his occupant), furnished with pieces from the Napoleonic and Habsburg periods and others from when the house was lived by the Pisani.

The most riotously splendid Tiepolo ceiling would influence his later depiction of the Glory of Spain for the throne room of the Royal Palace of Madrid; however, the grandeur and bombastic ambitions of the ceiling echo now contrast with the mainly uninhabited shell of a palace. The remainder of its nearly 100 rooms are now empty. The Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni described the palace in its day as a place of great fun, served meals, dance and shows.

Check out this sunken bathtub below:

Bear with me: in the next few photos I am trying out all of the fancy settings on my new camera:

To be continued.

Celebrating women art patrons: Tōfukumon’in, Empress Consort of Japan

Tōfukumon’in (1607–1678)

Empress Consort of Japan

Following more than a century of civil war in Japan, Empress Tōfukumon’in played a pivotal role in shaping culture and aesthetic tastes in the peaceful Edo period. Tōfukumon’in used her endowment from Tokugawa leadership to rebuild prominent Kyoto temples and collect art by her era’s leading artisans. She dabbled in creative endeavors herself, writing poetry and experimenting with calligraphy, and she was particularly interested in fashion and textiles.

Together with her husband, Gomizunoo, Tōfukumon’in fostered more direct relationships between the imperial family and artisans. The empress collected pottery by famed ceramicist Nonomura Ninsei, paintings by Tosa Mitsunobu, and works by other prominent artists and workshops of the day, like Tawaraya Sōtsatu and the Kano and Tosa schools. Her chambers featured artworks that mingled classical styles with contemporary scenes featuring warrior figures and commoners.

Among her most notable commissions are six painted screens by court painter Tosa Mitsuoki that together comprise Flowering Cherry and Autumn Maples with Poem Slips (1654–81). Against the golden silk backdrop, the artist rendered slips of medieval poetry dangling from finely wrought leaves. The work merges Tōfukumon’in’s interests in literature and painting, and also represents the royal couple’s quest for cultural influence in an era when the feudal shogunate increasingly wrestled control from the imperial family.

Celebrating women art patrons: Hürrem Sultan, a.k.a. Roxelana

Hürrem Sultan, a.k.a. Roxelana (1505–1558)

Empress of the Ottoman Empire

Titian, La Sultana Rossa c. 1500. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Through her coquetry and mastery of palace intrigue, Roxelana (meaning “the maiden from Ruthenia,” a region in what is today Belarus and Ukraine) rose from sex slavery as a concubine in Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent’s harem, eventually becoming his first (or most preferred) wife. In the harem, Roxelana learned Turkish, the principles of Islam, and the art of seduction, and she earned a new name, Hürrem—“the joyful one.” Roxelana so enchanted the sultan that he broke with tradition and had multiple children with her. A few years later, he married her—an act that granted Roxelana her freedom.

At the side of one of the most powerful rulers in Ottoman history, Roxelana wielded extraordinary influence over the empire through her philanthropy and prominent public building projects. Her Haseki complex in Constantinople featured a mosque, school, hospital, and soup kitchen. When a fire partially destroyed Suleiman’s harem, Roxelana used the opportunity to move in with her husband at the Topkapi Palace—an unprecedented move among sultanic wives that ushered in an era called “the Reign of Women.” Instead of rebuilding the harem, she encouraged Suleiman to construct a mosque.

The Mosque of Suleiman the Magnificent still stands as a landmark in Istanbul today. In The Women Who Built the Ottoman World (2017), Muzaffer Özgüles suggests that Roxelana “reshaped the patronage of all Ottoman women builders who came after her.”

The birth of Coty perfumes; how an up-start Corsican invented a bran

One of the many visitors to the Paris exposition was twenty-five-year-old François Spoturno (known to history as the more gentrified François Coty), a native of Corsica who had come to Paris to make his fortune. A born charmer, he already had proved his skills as a salesman in Marseilles. Now, using a connection he had cultivated during his military service, he found a position as attaché to the senator and playwright Emmanuel Arène. It was a tremendous coup.

Spoturno was born on 3 May 1874 in Ajaccio, Corsica. He was a descendant of Isabelle Bonaparte, an aunt of Napoleon Bonaparte. His parents were Jean-Baptiste Spoturno and Marie-Adolphine-Françoise Coti, both descendants of Genoese settlers who founded Ajaccio in the 15th century. His parents died when he was a child and the young François was raised by his great-grandmother, Marie Josephe Spoturno, and. after her death, by his grandmother, Anna Maria Belone Spoturno. Grandmother and grandson lived in Marseille.

Coty and his wife.

Young Spoturno may not have had money, but he now had access to the glittering upper reaches of 1900 Paris, with its salons, clubs, and fashionable gatherings. As he quickly realized, it was a world in which women played a key role, from the most elegant aristocrats to the grandest courtesans—a fact of great importance, as it turned out, since women would soon make Spoturno’s fortune.

Spoturno’s interest was not in clothing but in perfume. At the opening of the new century, the perfect perfume was as essential to the well-dressed Parisian woman as was the latest fashion in dresses, and the French perfume industry was booming, with nearly three hundred manufacturers, twenty thousand employees, and a profitable domestic as well as export business.4 Naturally, perfume makers took the opportunity to display their wares at the 1900 Paris exposition, and Spoturno took the time to wander among their displays, including those of leading names such as Houbigant and Guerlain.

Spoturno was not yet sufficiently knowledgeable to judge a perfume’s quality, but he did note that the bottles containing these perfumes were old-fashioned and uninspired. It would not be long before it would occur to him that perhaps their contents were also a trifle outdated.

But first he had to find his way into the perfume business. After getting a job as a fashion accessories salesman and marrying a sophisticated young Parisian, Spoturno became acquainted with a pharmacist who, like other chemists at the time, made his own eau de cologne, which he sold in plain glass bottles. He also met Raymond Goery, a pharmacist who made and sold perfume at his Paris shop. Coty began to learn about perfumery from Goery and created his first fragrance, Cologne Coty.

One memorable evening, Spoturno sniffed a sample of his friend’s wares and turned up his nose. The friend then dared him to make something better, and Spoturno went to work.

He hadn’t the slightest idea of how to proceed, but in the end he managed so well that his friend had to admit that he was gifted. Yet natural gifts were not enough in the perfume business, and soon Spoturno decided to go to Grasse, the center of France’s perfume industry, to learn perfume-making from the experts. Along the way he would change his name to his mother’s maiden name. Only he would spell it “Coty.”

The brand’s first fragrance, La Rose Jacqueminot, was launched the same year and was packaged in a bottle designed by Baccarat.

L’Origan was launched in 1905; according to The Week, the perfume “started a sweeping trend throughout Paris” and was the first example of “a fine but affordable fragrance that would appeal both to the upper classes and to the less affluent, changing the way scents were sold forever.”

Following its early successes, Coty was able to open its first store in 1908 in Paris’ Place Vendôme. Soon after, Coty began collaborating with French glass designer René Lalique to create custom fragrance bottles, labels, and other packaging materials, launching a new trend in mass-produced fragrance packaging.

Coty also established a “Perfume City” in the suburbs of Paris during the early 1910s to handle administration and fragrance production; the site was an early business supporter of female employees and offered benefits including child care.

The year was 1904, and François Coty was about to engage in his own act of rebellion. Or was it simply a superb marketing tactic? We do not know. What we do know is that on one fateful day, on the ground floor of the Louvre department store, Coty smashed a bottle of perfume on the counter—with momentous results. Following his decision to learn more about the perfume business, Coty had indeed gone to Grasse, which was the long-established center for cultivating the flowers essential for making perfume. It was also the research center for the entire perfume industry. There, he applied for training at the esteemed Chiris company, which represented the cutting edge of current perfume technology. Fortunately, the head of the firm, now a senator, was a friend of Coty’s patron, Senator Arène, which eased Coty’s way. Coty then worked diligently for a year to learn all that he could, from flower cultivation to essential oils, spending much of his time in the laboratory. He analyzed, he synthesized, and he learned how to blend. During his apprenticeship, Coty learned about two new tools that the established perfumers had for the most part neglected in favor of more traditional methods. The first of these was the discovery of extraction by volatile solvents, a technique that made extraction of large quantities of fragrance possible and could even be used with nonfloral substances such as leaves, mosses, and resins. Shortly before the turn of the century, Louis Chiris secured a patent on this technique and set up the first workshop based on solvent extraction. Coty was an early student of this pioneering work.

The second and even more revolutionary discovery was that of synthetic fragrances. Earlier in the nineteenth century, French and German scientists had discovered synthetic fragrance molecules in organic compounds such as coal and petroleum that allowed perfumers to approximate scents that could not otherwise be easily extracted. It was an amazing breakthrough, and a few perfumers experimented briefly with the artificial scents of sweet grass, vanilla (from conifer sap), violet, heliotrope, and musk. A few also explored the possibilities of the first aldehydes, which gave perfumes a far greater strength than ever before. Yet with only a few exceptions, established perfumers in the early 1900s avoided these synthetic molecules. In studying the successful perfumes of the day, Coty

concluded that most were limited in range and old-fashioned, pandering to conservative tastes with heavy, overly complex floral scents that were almost interchangeable. He had educated his nose and learned his trade, and although he never would become a perfumer per se, he had an extraordinary imagination and a gift for using it to explore new realms. It was with this gift, newly honed, that he returned to Paris, and with ten thousand borrowed francs set up a makeshift laboratory in the small apartment where he and his wife lived. He was willing—even eager—to break with convention, aiming to create a perfume that combined subtlety with simplicity. Even at the beginning, his formulas were simple but brilliant, using synthetics to enhance natural scents. Coty also revolutionized the

bottles containing his perfumes. Remembering the beauty of the antique perfume bottles at the 1900 Paris exposition, which made the virtually standardized perfume bottles of the day look boring, Coty unhesitatingly went to the top and hired Baccarat to produce the lovely, slim bottle for La Rose Jacqueminot, his first perfume. As he later remarked, “A perfume needs to attract the eye as much as the nose.”16 Coty’s wife sewed and embroidered the silk pouches with velvet ribbons and satin trim that contained the bottles, and Coty now drew on his sales skills—this time selling his own rather than someone else’s product. Much to his dismay, it proved almost impossible to break through the established perfumers’ stranglehold on the market. Coty went from rejection to rejection, until one day he lost his composure. He was on the

ground floor of the Louvre department store trying to sell La Rose Jacqueminot, and the buyer was about to show him the door. In anger—or in what perhaps was a supreme act of showmanship—Coty smashed one of the beautiful Baccarat bottles on the counter, and a revolution began. According to legend, women shoppers smelled the perfume and flocked to the source, buying up Coty’s entire supply. The buyer took note, became suddenly cooperative, and Coty was on his way. After the fact, some groused that Coty had staged the entire stunt, including hiring actresses to play the part of shoppers entranced by his perfume. Yet by this time it didn’t matter. Coty had made his first publicity coup, whether or not it was intentional, and he and his perfumes were launched.

François Coty was also doing well in new quarters, which he had shrewdly taken in an affluent part of town, just north of the Champs-Elysées. Space there was limited, but the address (on Rue La Boétie) was a good one and worth the effort to cram showroom, shop, laboratory, and packaging department under one small roof. Much as Coty expected and desired, his perfume business continued to surge. The year 1905 was a big one for him, during which he presented two new hits: Ambre Antique and, especially, L’Origan, which according to perfume aficionados was an exceptionally daring blend, suitable for those daring Fauvist times. It was while Coty was launching his seductive new perfumes that an ambitious young woman by the name of Helena Rubinstein was studying dermatology

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

The French Triumphal arch in Piazza della Liberta

The triumphal arch of the Lorraine, a gateway to and from power in Piazza della Libertà

There is a grandiose and quite ornate — at least by Tuscan standards — neoclassical arch standing in my neighborhood. It sits not quite in the middle of Piazza della Libertà.

Based on the model of Roman triumphal arches, the arch in Florence was built for the entry of Francesco Stefano, the First Grand Duke of the House of Lorraine, a dynasty imposed on Tuscany following the death in 1737 of the last of the Medici grand dukes, Gian Gastone.

Ironically, in 1859, the same arch saw the exit of the last of Tuscany’s Lorraine rulers, Grand Duke Leopoldo II, after he was ousted in a bloodless revolution.

In a kind of territorial “musical chairs,” the French, Austrians and dukes of Lorraine agreed under the peace treaty that ended the war of Polish succession (1733–37) that the duchy of Lorraine be given to Stanisław I, the former king of Poland and father-in-law of France’s King Louis XV. As compensation, the dukes of Lorraine were designated the duchy of Tuscany.

Thoroughly mystified by these geopolitical machinations, the Tuscans did not relish the idea of foreign occupation. Witness to this, French writer and future president of Burgundy Charles de Brosses commented that they would have willingly given “two-thirds of their property to have the Medicis back, and the other third to get rid of the Lorrainers….They hate them.”

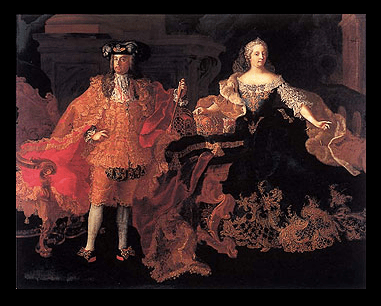

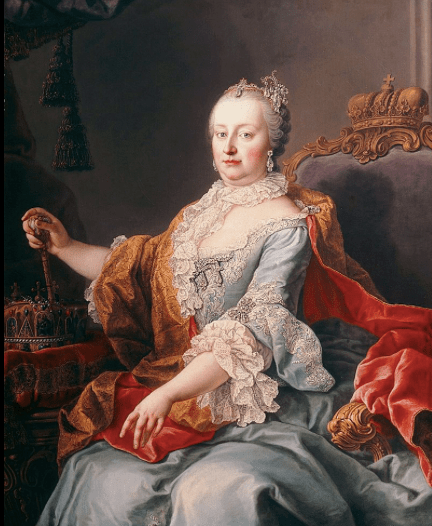

Nonetheless, to welcome the new sovereign, his young bride, Maria Theresa of Austria (the daughter and heir of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI), on their first –and only–visit to Florence in January 1739, Senator Carlo Ginori, founder of a porcelain factory, proposed the construction of an arch near the ancient Porta di San Gallo gate, which was and is the main northern entrance to the city.

Here’s a double portrait of the newlyweds:

The arch was designed by Jean-Nicolas Jador, an architect from Lorraine. Work began on December 16, 1738, but, despite more than 400 men working day and night, it was impossible to complete the complicated edifice on schedule for the couple’s arrival.

The three main arches, a large one in the centre with two smaller ones each side, were finished, but painted wood and canvas decorated with temporary statuary covered the section above them.

As the sound of cannons boomed out from Forte Belvedere and fireworks exploded into the sky, it is likely the grand duke could barely see these improvisations as night had almost fallen by the time he reached Florence on that cold winter’s day.

Work on the arch continued for another 20 years, with many artists and artisans involved before it was completed in 1759.

Supported by 10 Corinthian columns, the monument features 15 allegorical statues, heraldic decorations, four adornments of flags and arms, and six bas-reliefs of episodes from the life of Francesco Stefano, including his coronation.

On the southern façade, two double-headed eagles symbolize the Habsburg dynasty.

The monument is topped by an equestrian statue of Francesco Stefano by Florentine Baroque sculptor Vincenzo Foggini, known for his masterpiece Samson and the Philistines, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The statue faces away from the city, intended to welcome the grand duke and his entourage on his approach to the city from via Bolognese.

On that first visit, after celebrating mass at the Duomo, the royal couple took up residence in the Pitti Palace and spent their days sightseeing. During the carnival season, they held three lavish masked balls at the Palazzo Vecchio and even managed to attend a game of football in costume.

In describing Francesco Stefano in his Letters from Italy, John Boyle, the fifth earl of Cork and Orrery, wrote that he was “of a cheerful aspect, and of a most princely personage, yet something sinister and obscure may be perceived in his countenance … He is a Lorrainese, the shadow, not the substance of a sovereign.”

Here he is in a portrait:

And it was the shadow of Francesco Stefano that would, in fact, reign over his subjects because his stay, albeit it a pleasant one, lasted only three months, and he would never set foot in the city again. After the death of Charles VI in 1740, Maria Theresa succeeded her father and named her husband co-regent of the Holy Roman Empire.

For the next 27 years, Tuscany was governed in his name by a regency, first by Count Emmanuel de Richecourt and then by General Antonio Botta-Adorno.

In effect, Florence and the region simply became a convenient cash cow to be heavily taxed and plundered of its art or of whatever else could be of use to the court in Vienna for supporting its economy and the Austrian army.

http://www.theflorentine.net/art-culture/2016/05/triumphal-arch-lorraine/

Florence’s tiny little wine windows

One of the hundreds of interesting things you see when walking around the city of Florence are these small windows, measuring about 12 inches wide by 15 inches tall, cut into the masonry of some major palazzi. There are hundreds of them in Florence.

The buchette del vino (“small holes [for] wine”) were added to the buildings by entrepreneurial families who produced wine on their country estates and thought to themselves, “why not sell some in Florence on a glass by glass, or a refilled bottle by bottle, basis?”

Together, these windows form a collection of Renaissance-era vestiges of a once-popular and admirably no-fuss form of wine sales.

Without exception, I have never seen one of these windows open. They are usually boarded up, sometimes in quite decorative ways.

But now, an organization is working to preserve—and help reopen—the city’s “wine windows.”

“These small architectural features are a very special commercial and social phenomenon unique to Florence and Tuscany,” Matteo Faglia, a founding member of the Associazione Culturale Buchette del Vino, told Unfiltered via email. “Although they are a minor cultural patrimony, nevertheless, they are an integral part of the richest area of the world in terms of works of art and monuments—Tuscany.”

The buchette first came into vogue in the 16th century, when wealthy Florentines began to expand into landowning—notably, owning vineyards—in the Tuscan countryside. The aristocrats’ new zeal for selling wine was matched only by that for avoiding paying taxes on selling wine, so they devised the simplest model for wine retail they could: on-demand, to-go, literally hand-sold through a hole in the wall of their residences.

It was convenient for drinkers, too: Knock on the window with your empty bottle, and the server, a cantiniere, would answer; upon receiving the bottle and payment, he would return with a full bottle of wine. Buchette eventually became popular enough that nearly every Florentine family with vineyards and a palace in Florence had a wine window, and soon the trend spread to nearby Tuscan towns like Siena and Pisa.

The windows stayed open for the next three centuries, but by the beginning of the 20th century, more social wine tavernas had spread throughout the city, with better-quality wine, better company and equally easy access to a flask.

By 2015, most Florentines had lost track of their wine windows, if not vandalized them. That year, the Associazione was founded, with a mission to identify, map and preserve the buchette—nearly 300 catalogued so far.

And this summer provided a new boost to their work: One restaurant has cracked open its buchetta anew for business. Babae is the first restaurant to re-embrace the old tradition, filling glasses for passersby through their buchetta for a few hours each evening.

It’s a welcome development to the lovers of wine windows. “Although the ways of selling wine have obviously changed since the wine windows were fully active … this small gesture, which highlights a niche of Florentine history, is very welcome,” said Faglia, “to help to keep alive this antique and unique way of selling one of Tuscany’s most important agricultural and commercial products: its wine.”

This new association even has a Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/buchettedelvino/

The wonders of Padua (Padua, part 3)

Padova or Padua is a big subject! I’ve recently posted 2 times about it, here, here, here and here. And, still, I am far from done!

This post includes a list of the major features that grace this lovely, historic town. But first, a sweet little video about the town itself:

Undoubtedly the most notable things about Padova is the Giotto masterpiece of fresco painting in the The Scrovegni Chapel (Cappella degli Scrovegni). This incredible cycle of frescoes was completed in 1305 by Giotto.

It was commissioned by Enrico degli Scrovegni, a wealthy banker, as a private chapel once attached to his family’s palazzo. It is also called the “Arena Chapel” because it stands on the site of a Roman-era arena.

The fresco cycle details the life of the Virgin Mary and has been acknowledged by many to be one of the most important fresco cycles in the world for its role in the development of European painting. It is a miracle that the chapel survived through the centuries and especially the bombardment of the city at the end of WWII. But for a few hundred yards, the chapel could have been destroyed like its neighbor, the Church of the Eremitani.

The Palazzo della Ragione, with its great hall on the upper floor, is reputed to have the largest roof unsupported by columns in Europe; the hall is nearly rectangular, its length 267.39 ft, its breadth 88.58 ft, and its height 78.74 ft; the walls are covered with allegorical frescoes. The building stands upon arches, and the upper story is surrounded by an open loggia, not unlike that which surrounds the basilica of Vicenza.

The Palazzo was begun in 1172 and finished in 1219. In 1306, Fra Giovanni, an Augustinian friar, covered the whole with one roof. Originally there were three roofs, spanning the three chambers into which the hall was at first divided; the internal partition walls remained till the fire of 1420, when the Venetian architects who undertook the restoration removed them, throwing all three spaces into one and forming the present great hall, the Salone. The new space was refrescoed by Nicolo’ Miretto and Stefano da Ferrara, working from 1425 to 1440. Beneath the great hall, there is a centuries-old market.

In the Piazza dei Signori is the loggia called the Gran Guardia, (1493–1526), and close by is the Palazzo del Capitaniato, the residence of the Venetian governors, with its great door, the work of Giovanni Maria Falconetto, the Veronese architect-sculptor who introduced Renaissance architecture to Padua and who completed the door in 1532.

Falconetto was also the architect of Alvise Cornaro’s garden loggia, (Loggia Cornaro), the first fully Renaissance building in Padua.

Nearby stands the il duomo, remodeled in 1552 after a design of Michelangelo. It contains works by Nicolò Semitecolo, Francesco Bassano and Giorgio Schiavone.

The nearby Baptistry, consecrated in 1281, houses the most important frescoes cycle by Giusto de’ Menabuoi.

The Basilica of St. Giustina, faces the great piazza of Prato della Valle.

The Teatro Verdi is host to performances of operas, musicals, plays, ballets, and concerts.

The most celebrated of the Paduan churches is the Basilica di Sant’Antonio da Padova. The bones of the saint rest in a chapel richly ornamented with carved marble, the work of various artists, among them Sansovino and Falconetto.

The basilica was begun around the year 1230 and completed in the following century. Tradition says that the building was designed by Nicola Pisano. It is covered by seven cupolas, two of them pyramidal.

Donatello’s equestrian statue of the Venetian general Gattamelata (Erasmo da Narni) can be found on the piazza in front of the Basilica di Sant’Antonio da Padova. It was cast in 1453, and was the first full-size equestrian bronze cast since antiquity. It was inspired by the Marcus Aurelius equestrian sculpture at the Capitoline Hill in Rome.

Not far from the Gattamelata are the St. George Oratory (13th century), with frescoes by Altichiero, and the Scuola di S. Antonio (16th century), with frescoes by Tiziano (Titian).

One of the best known symbols of Padua is the Prato della Valle, a large elliptical square, one of the biggest in Europe. In the center is a wide garden surrounded by a moat, which is lined by 78 statues portraying illustrious citizens. It was created by Andrea Memmo in the late 18th century.

Memmo once resided in the monumental 15th-century Palazzo Angeli, which now houses the Museum of Precinema.

The Abbey of Santa Giustina and adjacent Basilica. In the 5th century, this became one of the most important monasteries in the area, until it was suppressed by Napoleon in 1810. In 1919 it was reopened.

The tombs of several saints are housed in the interior, including those of Justine, St. Prosdocimus, St. Maximus, St. Urius, St. Felicita, St. Julianus, as well as relics of the Apostle St. Matthias and the Evangelist St. Luke.

The abbey is also home to some important art, including the Martyrdom of St. Justine by Paolo Veronese. The complex was founded in the 5th century on the tomb of the namesake saint, Justine of Padua.

The Church of the Eremitani is an Augustinian church of the 13th century, containing the tombs of Jacopo (1324) and Ubertinello (1345) da Carrara, lords of Padua, and the chapel of SS James and Christopher, formerly illustrated by Mantegna’s frescoes. The frescoes were all but destroyed bombs dropped by the Allies in WWII, because it was next to the Nazi headquarters.

The old monastery of the church now houses the Musei Civici di Padova (town archeological and art museum).

Santa Sofia is probably Padova’s most ancient church. The crypt was begun in the late 10th century by Venetian craftsmen. It has a basilica plan with Romanesque-Gothic interior and Byzantine elements. The apse was built in the 12th century. The edifice appears to be tilting slightly due to the soft terrain.

Botanical Garden (Orto Botanico)

The church of San Gaetano (1574–1586) was designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi, on an unusual octagonal plan. The interior, decorated with polychrome marbles, houses a Madonna and Child by Andrea Briosco, in Nanto stone.

The 16th-century Baroque Padua Synagogue

At the center of the historical city, the buildings of Palazzo del Bò, the center of the University.

The City Hall, called Palazzo Moroni, the wall of which is covered by the names of the Paduan dead in the different wars of Italy and which is attached to the Palazzo della Ragione

The Caffé Pedrocchi, built in 1831 by architect Giuseppe Jappelli in neoclassical style with Egyptian influence. This café has been open for almost two centuries. It hosts the Risorgimento museum, and the near building of the Pedrocchino (“little Pedrocchi”) in neogothic style.

There is also the Castello. Its main tower was transformed between 1767 and 1777 into an astronomical observatory known as Specola. However the other buildings were used as prisons during the 19th and 20th centuries. They are now being restored.

The Ponte San Lorenzo, a Roman bridge largely underground, along with the ancient Ponte Molino, Ponte Altinate, Ponte Corvo and Ponte S. Matteo.

There are many noble ville near Padova. These include:

Villa Molin, in the Mandria fraction, designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1597.

Villa Mandriola (17th century), at Albignasego

Villa Pacchierotti-Trieste (17th century), at Limena

Villa Cittadella-Vigodarzere (19th century), at Saonara

Villa Selvatico da Porto (15th–18th century), at Vigonza

Villa Loredan, at Sant’Urbano

Villa Contarini, at Piazzola sul Brenta, built in 1546 by Palladio and enlarged in the following centuries, is the most important

Padua has long been acclaimed for its university, founded in 1222. Under the rule of Venice the university was governed by a board of three patricians, called the Riformatori dello Studio di Padova. The list of notable professors and alumni is long, containing, among others, the names of Bembo, Sperone Speroni, the anatomist Vesalius, Copernicus, Fallopius, Fabrizio d’Acquapendente, Galileo Galilei, William Harvey, Pietro Pomponazzi, Reginald, later Cardinal Pole, Scaliger, Tasso and Jan Zamoyski.

It is also where, in 1678, Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopia became the first woman in the world to graduate from university.

The university hosts the oldest anatomy theatre, built in 1594.

The university also hosts the oldest botanical garden (1545) in the world. The botanical garden Orto Botanico di Padova was founded as the garden of curative herbs attached to the University’s faculty of medicine. It still contains an important collection of rare plants.

The place of Padua in the history of art is nearly as important as its place in the history of learning. The presence of the university attracted many distinguished artists, such as Giotto, Fra Filippo Lippi and Donatello; and for native art there was the school of Francesco Squarcione, whence issued Mantegna.

Padua is also the birthplace of the celebrated architect Andrea Palladio, whose 16th-century villas (country-houses) in the area of Padua, Venice, Vicenza and Treviso are among the most notable of Italy and they were often copied during the 18th and 19th centuries; and of Giovanni Battista Belzoni, adventurer, engineer and egyptologist.

The sculptor Antonio Canova produced his first work in Padua, one of which is among the statues of Prato della Valle (presently a copy is displayed in the open air, while the original is in the Musei Civici).

The Antonianum is settled among Prato della Valle, the Basilica of Saint Anthony and the Botanic Garden. It was built in 1897 by the Jesuit fathers and kept alive until 2002. During WWII, under the leadership of P. Messori Roncaglia SJ, it became the center of the resistance movement against the Nazis. Indeed, it briefly survived P. Messori’s death and was sold by the Jesuits in 2004.

Paolo De Poli, painter and enamellist, author of decorative panels and design objects, 15 times invited to the Venice Biennale was born in Padua. The electronic musician Tying Tiffany was also born in Padua.

The history of Padua, including the city walls, part 2

The rich history of Padua was only partially discussed here. This post continues the story.

Beginning with the 12th Century in Padova:

The Carrara Family, also called Carraresi, was a medieval Italian family who ruled first as feudal lords about the village of Carrara in the countryside near Padua and then as moderately enlightened despots in the city of Padua.

Having moved into Padua itself in the 13th century, the Carraresi exploited the feuds of urban politics first as Ghibelline and then as Guelf leaders and were thus able to found a new and more illustrious dominion. The latter began with the election of Jacopo da Carrara as perpetual captain general of Padua in 1318 but was not finally established, with Venetian help, until the election of his nephew Marsiglio in 1337.

For approximately 50 years, the Carraresi ruled with no serious rivals except among members of their own family. Marsiglio was succeeded without incident by Ubertino (1338–45), but Marsigliello, who succeeded Ubertino, was deposed and murdered by Jacopo di Niccolò (1345–50).

Jacopo was then murdered by Guglielmino and succeeded by his brother Jacopino di Niccoló (1350–55), and Jacopino in turn was dispossessed and imprisoned by his nephew Francesco il Vecchio (1355–87). Such a nice family to call your own.

Despite this chaos, the Carrara court was one of the most brilliant in all of the Italian peninsula. Ubertino in particular was a patron of building and the arts, and Jacopo di Niccolò was a close friend of Petrarch.

Only with the exception of a brief period of Scaligeri (the ruling family in Verona) overlordship between 1328 and 1337 and two years (1388–1390) when Giangaleazzo Visconti held the town, Padua was pretty much owned by the Carraresi.

The many advances of Padova in the 13th century naturally brought the commune into conflict with Can Grande della Scala, lord of Verona. In 1311, Padua had to yield.

But, even under the Carraresi, it was a long period of restlessness, for the Carraresi were constantly at war. Under Carraresi rule, the early humanist circles at the University of Padua were effectively disbanded: Albertino Mussato, the first modern poet laureate, died in exile at Chioggia in 1329, and the eventual heir of the Paduan literary tradition went to the Tuscan Petrarch.

In 1387, John Hawkwood won the Battle of Castagnaro for Padua, against Giovanni Ordelaffi, for Verona.

The Carraresi period finally came to an end as the power of the Visconti and of Venice grew in importance. Padova came under the rule of the Republic of Venice in 1405, and mostly remained that way until the fall of the Republic of Venice in 1797.

There was just a brief period when the city changed hands (in 1509) during the wars of the League of Cambrai. Padova was held for just a few weeks by Imperial supporters, but Venetian troops quickly recovered it and successfully defended Padua during a siege by Imperial troops (Siege of Padua).

As a part of the Venetian Republic, Padova was governed by two Venetian nobles, a podestà for civil affairs and a captain for military affairs. Each was elected for 16 months. Under these governors, the great and small councils continued to discharge municipal business and to administer the Paduan law, contained in the statutes of 1276 and 1362. The treasury was managed by two chamberlains; and every five years the Paduans sent one of their nobles to reside as nuncio in Venice; this elected official was in place to watch out for the interests of his native town.

The City Walls:

For more information see: https://digilander.libero.it/clapad5/padova/mura.html

1. The Romans would seem to be the first to surround Padova with walls. Of the walls built during the ancient Roman era, the only traces to survive are those incorporated into the foundations of certain palazzi. The route of these walls corresponded to a meandering line formed by the river Medoacus (now the Brenta). Inside the walls, Padua’s first urban center developed.

2. The Mura Duecentesche (“13th century walls”; aka the mura comunali or mura medievali) were built at the start of the 13th century by the Comune of Padua. Their route was delimited by the two branches of the Bacchiglione, the Tronco Maestro and the Naviglio Interno, which came to be used as defensive ditches. There are several remains of them around the Castello and near Porta Molino. More minor remains are to be found in the Riviera Tito Livio and Riviera Albertino Mussato; the only gates to remain from this wall are the main north gate, Porta Molino (or Molini, after several mills in the area which functioned up to the early 20th century), and the main west gate, Porta Altinate (named after the road to Altino which began here).

(The Porta Molino‘s upper stories were used at the end of the 19th century as a reservoir for the town’s first drinking water system; tales of the tower being used as an observatory by Galileo Galilei during his time in the city are probably false. The Porta Altinate fronted onto the Naviglio Interno, crossed by an ancient Roman three-arch bridge, and in 1256 this gate was stormed and destroyed by crusaders fighting against Ezzelino da Romano [as recorded in an inscription recorded by Carlo Leoni]. It was rebuilt in 1286. The Naviglio and the bridge were buried in the 1960s.)

3. 14th century, the Mura Carraresi were built by the Carraresi in the 14th century and followed a route that would be followed almost by the later 16th century wall. Almost nothing remains of them the Mura Carraresi, since they were demolished during the War of the League of Cambrai to create the Renaissance wall. However, some sections can be seen in via delle Dimesse, near the Prato della Valle.

4. The Mura Cinquecentesche (16th century Walls; aka the Mura rinascimentali or Mura Veneziane) were built to protect Padova by the Venetian Republic during the first decades of the 16th century. It was a project of the condottiero Bartolomeo d’Alviano.

Canaletto, View of Padua from outside the city walls with the Church of San Francesco and the Palazzo della Salone

The Mura rinascimentali were protected on their west flank by a canal known as the fossa Bastioni, which still exists. The Renaissance walls survive to this day, almost entirely unbroken apart from sections demolished in the 1960s to build the new Ospedale Civile.

The City Gates:

Nearly all the walls’ gates survive. For even more information, see: http://digilander.libero.it/clapad5/padova/porte.html

Porta Savonarola – Completed in 1530. Designed by the architect Giovanni Maria Falconetto, this gate was built with a frieze showing the Lion of Saint Mark, symbol of the Venetian Republic, which still survives. Picture below:

Porta san Giovanni – Completed in 1528. Designed by the architect Giovanni Maria Falconetto, this gate originally had a frieze showing the Lion of Saint Mark, symbol of the Venetian Republic (the frieze here was destroyed during the Napoleonic Wars). Picture below:

Porta Ognissanti (or Portello, Portello Nuovo or Portello Venezia) – Originally entitled Portello or Little Port, the gate was built at the terminus for the river trade along the Brenta between Padua and Venice. The present building replaces the Portello Vecchio, on what is now via San Massimo, but is rather different from the city’s other gates of this date – the external facade is adorned with shining rocks from Istria, with four pairs of columns surmounted by an architrave embellished with four trachyte cannonballs. The three-arch bridge carrying the road over the Canale Piovego and through the gate is guarded by two white stone lions. Stones in the gate (still legible today) commemorate the ancient origins of the town, speaking to “its good governance.” Since 1535, a clock stands out from the gate in Nanto stone. Traces of frescoes can also be seen inside the gate. 5 pictures below:

Porta Liviana – Begun in 1509, it was completed in 1517 and named in honour of Bartolomeo d’Alviano himself.

Porta Santa Croce – On the site of a gate in the Carraresi wall, the present gate was begun in 1509 and was originally defended by a tower, demolished in 1632.

(For a walk to view the city walls, you can start from Piazza Garibaldi, where there is the medieval Porta Altinate (1286), one of the 3 oldest city gates, with short sections of walls still visible at various points of the Ponte Romani and Tito Livio rivers, then walk along via San Fermo (with the church of the same name leaning against the city walls). Walk from the Largo Europe and the Riviera Mugnai until you reach the intersection with via Dante, then you arrive at the 2nd medieval gate, Porta Ponte Molino, with its large pointed arch surmounted by a mighty tower.)

The End of the Venetian Republic:

In 1797, the Venetian Republic came to an end with the Treaty of Campo Formio, and Padua, like much of the Veneto, was ceded to the Habsburgs. In 1806, the city passed to the French puppet Kingdom of Italy until the fall of Napoleon, in 1814, when the city became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, part of the Austrian Empire.

Austrian rule was unpopular with progressive circles in northern Italy, but the feelings of the population (from the lower to the upper classes) towards the empire were mixed.

In Padua, the year of revolutions of 1848 saw a student revolt which on 8 February turned the University and the Caffè Pedrocchi into battlegrounds where students and Paduans fought side by side. The revolt was, however, short-lived and there were no further episodes of unrest under the Austrian Empire (nor previously had there been any), as in Venice or in other parts of Italy. The opponents of Austria were forced into exile.

Under Austrian rule, Padua began its industrial development; one of the first Italian rail tracks, Padua-Venice, was built in 1845. In 1866, the Battle of Königgrätz gave Italy the opportunity, as an ally of Prussia, to take Veneto, and Padova was also annexed to the recently formed Kingdom of Italy.

At that time, Padova was at the center of the poorest area of Northern Italy, as the Veneto was until the 1960s. Despite this, the city flourished in the following decades both economically and socially, developing its industry, being an important agricultural market and having a very important cultural and technological center as the University. The city hosted also a major military command and many regiments.

The 20th Century:

When Italy entered World War I on 24 May 1915, Padova was chosen as the main command of the Italian Army. The king, Vittorio Emanuele III, and the commander in chief, Cadorna, lived in Padua for the period of the war.

After the defeat of Italy in the battle of Caporetto in autumn 1917, the front line became the river Piave, only about 35 miles from Padua. This put the city in the range of the Austrian artillery. However, the Italian military command did not withdraw. The city was bombed several times, with about 100 civilian deaths. A memorable feat was Gabriele D’Annunzio’s flight to Vienna from the nearby San Pelagio Castle airfield.

In 1918, the threat to Padua was removed. In late October, the Italian Army won the decisive Battle of Vittorio Veneto, and the Austrian forces collapsed. The armistice was signed at Villa Giusti, Padua, on 3 November 1918.

During the war, industry grew rapidly, and this provided Padua with a base for further post-war development. In the years immediately following WWI, Padua grew outside the historical town, despite the fact that labor and social strife were rampant at the time.

As in many other areas in Italy, Padua experienced great social turmoil in the years immediately following World War I. The city was shaken by strikes and clashes, factories and fields were subject to occupation, and war veterans struggled to re-enter civilian life. Many supported a new political way, fascism.

As in other parts of Italy, the National Fascist Party in Padua soon came to be seen as the defender of property and order against revolution. Padua was the site of one of the largest fascist mass rallies, with some 300,000 people reportedly attending one speech by Benito Mussolini.

New buildings, in fascist architectural style, sprang up in the city. Examples can be found today in the buildings surrounding Piazza Spalato (today Piazza Insurrezione), the railway station, the new part of City Hall, and part of the Palazzo Bo hosting the University.

Following Italy’s defeat in WWII on 8 September 1943, Padua became part of the Italian Social Republic, which was a puppet state of the Nazi occupiers. The city hosted the Ministry of Public Instruction of the new state, as well as military and militia commands and a military airport.

The Resistenza, the Italian partisans, was very active against both the new fascist rule and the Nazis. One of the main leaders of the Resistenza in the area was the University vice-chancellor Concetto Marchesi.

Toward the end of the war, as the Allied Command freed Italy from German occupation moving from south to north, Padua was unfortunately bombed several times by Allied planes. The worst hit areas were the railway station and the northern district of Arcella. Because of the location of the German command center in Padua, it was during one of these bombings that the Church of the Eremitani took a direct hit. It was a miracle of sorts that the nearby Scrovegni Chapel was not hit as well.

You can see on the map below how close the Scrovegni is to the church (Chiesa degli Eremitani on the map).

Tragically, the Church of the Eremitani was graced with some of the finest frescoes by Andrea Mantegna and they were almost complete obliterated. This is considered by some art historians to be Italy’s biggest wartime cultural loss.

Art conservators have been able to do the almost impossible and stitch together the remnants of the frescoes as seen in the next picture. I’ll be posting about the frescoes soon.

The city was liberated by partisans and the 2nd New Zealand Division of the British Eighth Army on 28 April 1945. A small Commonwealth War Cemetery is located in the west part of the city, commemorating the sacrifice of these troops.

After the war, the city developed rapidly, reflecting Veneto’s rise from being the poorest region in northern Italy to one of the richest and most economically active regions of modern Italy.

The subject of Padua is vast. I’ll be posting yet more very soon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.