Italian Renaissance art

What made a Florentine a Florentine during the time of Michelangelo?

Check it out!

100 Artistic Treasures in Florence

I’m taking a course this week at the British Institute. The art history department there has designed this course to look at 100 treasures in Florence. I am almost positive I’ll post more about this course!

https://www.britishinstitute.it/media/docs/Combined/CT%202018.%20SAMPLE%20PROGRAMME.pdf

Inexpensive paper helped fuel the Renaissance.

A plentiful supply of paper – just as much as the study of ancient sculpture or single-point perspective – was among the factors that led to what we call the Renaissance. It allowed artists to think and work in different ways, a transformation as significant as the Internet and computer technology have been in the early twenty-first century.

Not, of course, that paper itself was a new material in the fifteenth century. On the contrary, it had first been made in China a millennium and a half previously; but the recent availability of paper was a knock-on effect of another innovation: the invention of moveable type by Johann Gutenberg of Mainz.

By 1450 Gutenberg had set up a commercial printing press, and by the 1460s presses began to be established in Italy. As soon as that happened, there was a greater demand for paper, so more paper mills were built.

The main alternative for drawing had been vellum – scraped and burnished calf-, sheep- or goat-skin – which was luxurious and labour intensive to prepare. The price list of a Florentine stationer’s from the 1470s lists vellum as fourteen times more expensive than paper.

Paper, however, was still quite a costly material. That was why artists often used both sides of a sheet; it was too valuable to waste.

So, after Ghirlandaio had used a piece of paper to work out the composition of The Visitation, one of the frescoes for the Tornabuoni Chapel, in a flurry of rapid pen strokes – establishing the positions of the figures, jotting down the background architecture – the paper was then turned over and used as a cartoon for a piece of classical moulding framing the scenes.

A series of holes was then pricked through, following the lines of the egg and dart and palmette motifs, and charcoal or black chalk dust forced through them to transfer the lines to the wall.

Always acutely cost-conscious, Michelangelo was an especially assiduous recycler of used paper, sometimes searching through the litter in his studio for a useable scrap and coming up with a sheet he had drawn on years before but which still retained some blank space.

As a result, Michelangelo’s drawings, even more than those of, say, Leonardo, are palimpsests on which one may find jostling each other sketches and studies for various projects side by side with drafts of poems, stray remarks or quotations that seem to have drifted through his mind, lists of expenses and other items that are apparently not by Michelangelo at all. His correction of another apprentice’s attempt to copy those

Gayford, Martin. Michelangelo: His Epic Life (Kindle Locations 1045-1054). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

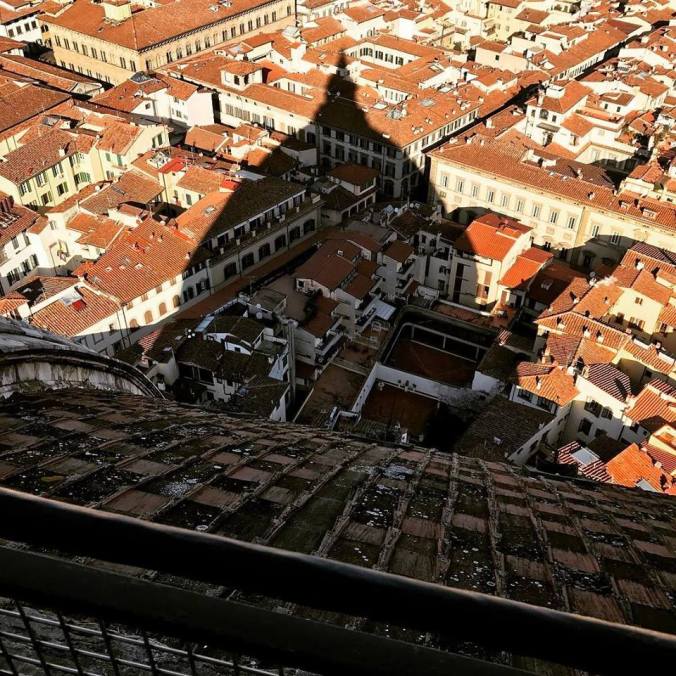

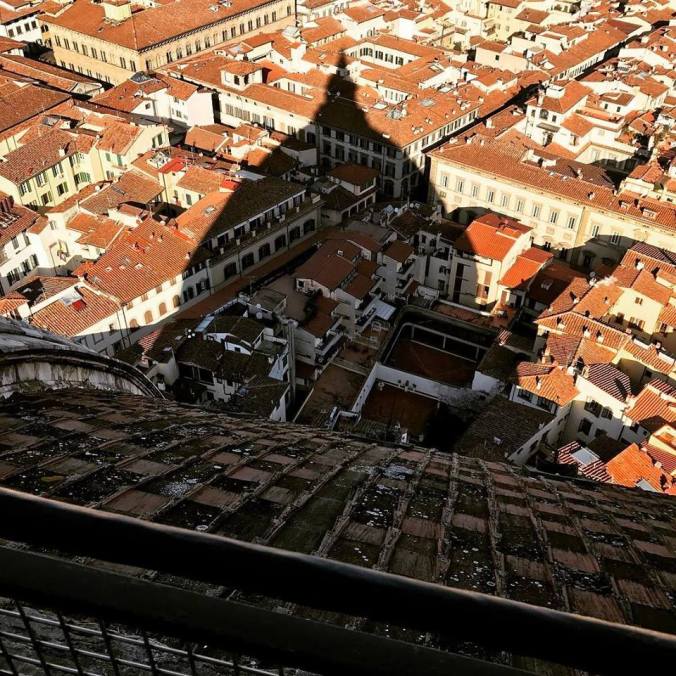

Palazzo Medici, Firenze

Today, it was gorgeous against an azure sky

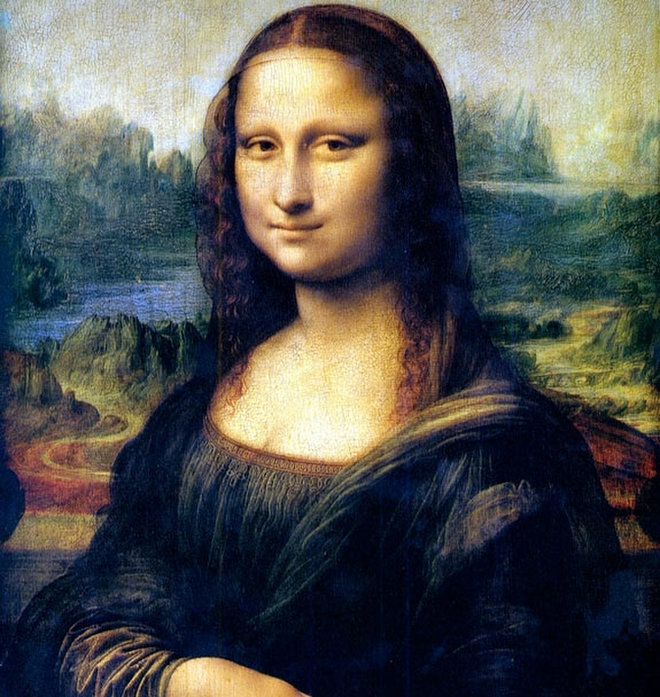

The virtues of a painting, according to Leonardo

The Mona Lisa was, when finally completed, a supreme demonstration of what, in Leonardo’s view, painting could do: create misty distances, delicate colours, soft naturalism, convey the mysteries of human emotion through facial expression and, in the vast landscape behind Lisa, provide a mirror of the cosmos: ‘sea and land, plants and animals, grasses and flowers, all enveloped in light and shade’.

Gayford, Martin. Michelangelo: His Epic Life (p. 187). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

Before oil paint came in tubes…

If you admire great paintings, you’ll be even more in awe when you consider that for most of history, artists had to make their own paint from oil, pigment, and sometimes eggs. Watch this video to see the process and as a plus, you can practice your Italian skills!

How to create a Renaissance panel painting

The technique and materials are made clear in this excellent video. Then, all you need is talent!

Interest in Michelangelo reigns

Persimmons in Arezzo

I love a pretty garden, even in the winter. I was in Arezzo recently and paid a visit to the Vasari Casa museum. If you know Vasari’s monumental book on Italian artists (the first of its kind, published in the 16th century), you know how important he is for more or less beginning the field of art history. As such, he is sort of my patron saint, with lower case letters.

So I was delighted to visit Vasari’s home in Arezzo, and ponder how it was his refuge from the busy life he led in Florence. But, as often happens for me, while I found his modest palazzo to be interesting for it’s structure and fresco decorations (much of it Vasari himself), it was the garden that drew me like a magnet.

And in his garden I spied this beautiful, ancient persimmon tree. I love how the tree looks without any leaves: only brown bark, branches, and the fruit that look like Christmas decorations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.