How lovely to stop by and see this old friend for an hour or so on a winter afternoon. Masaccio’s work is always a joy to behold!

So many churches, so little time. You really have to manage your real life if you want to find time to see everything!

At least, that is my excuse as to why, before now, I have never before been in this famous Florentine church. Plus the fact that when I pass it, I am usually in a hurry to go somewhere else nearby. Like, for example, lunch or a glass of wine at the Cantinetta Antinori, one of my favorite places in this amazing city.

But, I did stop in and have a gander at the church recently and wow, I was blown away. First of all, it was twilight in beautiful Florence at that moment, and the streets nearby were filled with shoppers and tourists and the whole atmosphere was electric. The city felt alive.

Usually, when I happen to be in front of this church, it is closed. Just bad timing, because of course the church is open everyday, but at specific hours.

Because it was open and I had time, I entered. I felt the richness of the interior immediately. And I was sorry it took me so long to visit.

Unlike so many Italian churches, this interior was well lit and the contrast of the dark building materials with the colored marbles and gold highlights lit the place up like a Christmas tree. The effect was quite something.

The church was also full of people, unlike so many Italian churches. The church interior felt alive and it was kind of a magical moment to me. I thought of how happy the founders would have been to know that in 2019, their church was an active part of the city’s life. What more could an architect or patron hope for?

I wonder why it is that I am always, always most attracted to sculptures holding up the vases of holy water in these churches?

The two matching marble holy water fonts at the entrance were sculpted in the form of shells supported by angels by Domenico Pieratti.

The pictures below aren’t great, but smack dab in the middle of the ceiling over the transept, was the Medici shield. Never subtle, always evident. I love the Medici family!

Let’s have a quick look at what Wikipedia tells us about the church:

San Gaetano, also known as Santi Michele e Gaetano, is a Baroque church in Florence, located on the Piazza Antinori.

A Romanesque church, dedicated solely to Saint Michael the Archangel, had been located at the site for centuries prior to its Baroque reconstruction. Patronized by the Theatine order, the new church was dedicated to Saint Cajetan, one of the founders of the order, though the church could not formally be named after him until his canonisation in 1671.

Funding for this reconstruction was obtained from the noble families in Florence, including the Medicis. Cardinal Carlo de’ Medici was particularly concerned with the work, and his name is inscribed on the façade.

Building took place between 1604 and 1648. The original designs were by Bernardo Buontalenti but a number of architects had a hand in building it, each of whom changed the design. The most important architects were Matteo Nigetti and Gherardo Silvani.

In 2008, the church was entrusted to the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest, a traditional institute of clerical life which exclusively offers Mass in Latin according to the pre-Vatican II Roman Rite.

The façade has three portals: the center portal has a triangular tympanum surmounted by reclining marble statues representing Faith and Charity, sculpted by the Flemish artist, Baldassarre Delmosel. In the center above the door is the heraldic shield of the Theatine order; higher above is the shield of Cardinal Giovanni Carlo de Medici, a prominent patron. Above the side doors are a statue of St Cajetan (right, by the same Delmosel) and St Andrew Avellino (left, by Francesco Andreozzi).

The interior is richly decorated as is customary in Baroque churches (uh, hello…the interior is like a jewel box!)

Along the cornice are 14 statues depicting apostles and evangelist, sculpted by Novelli, Caccini, Baratta, Foggini, Piamontini, Pettirossi, Fortini, and Cateni. With each of these statues is a bas-relief depicting an event in the life of each saints.

If you’ve been to Florence, you know how the hordes of tourists can dampen the spirit of art appreciation. Think of the Uffizi and you know what I mean.

But, there are several places in Florence where you can view Renaissance art up close and personal and rarely have another soul in the room with you.

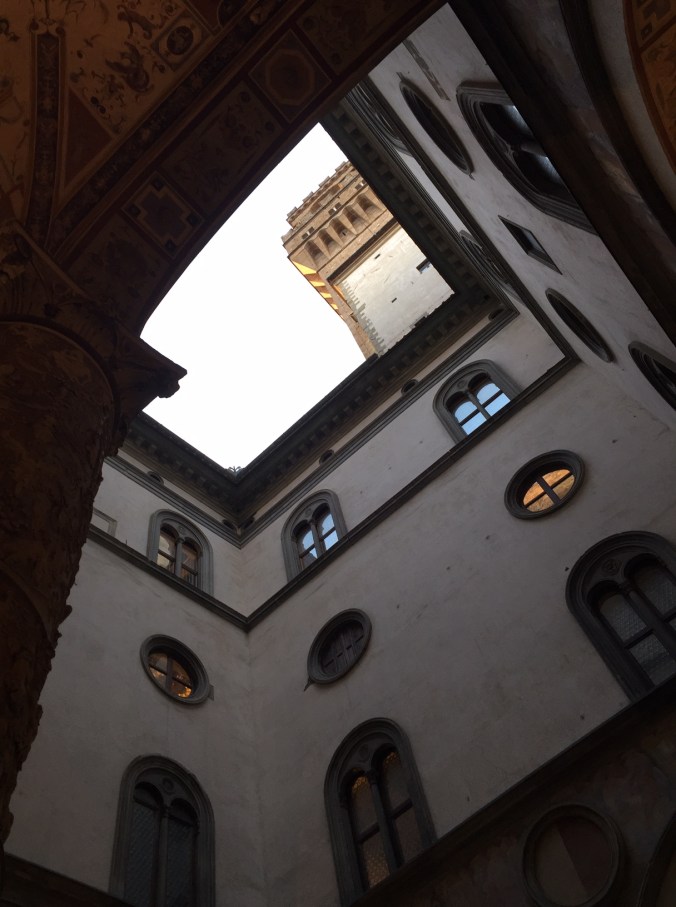

One of the most amazing of these places is housed within this entrance:

I mean, really, would you even know there was anything at all inside, let alone a masterpiece?

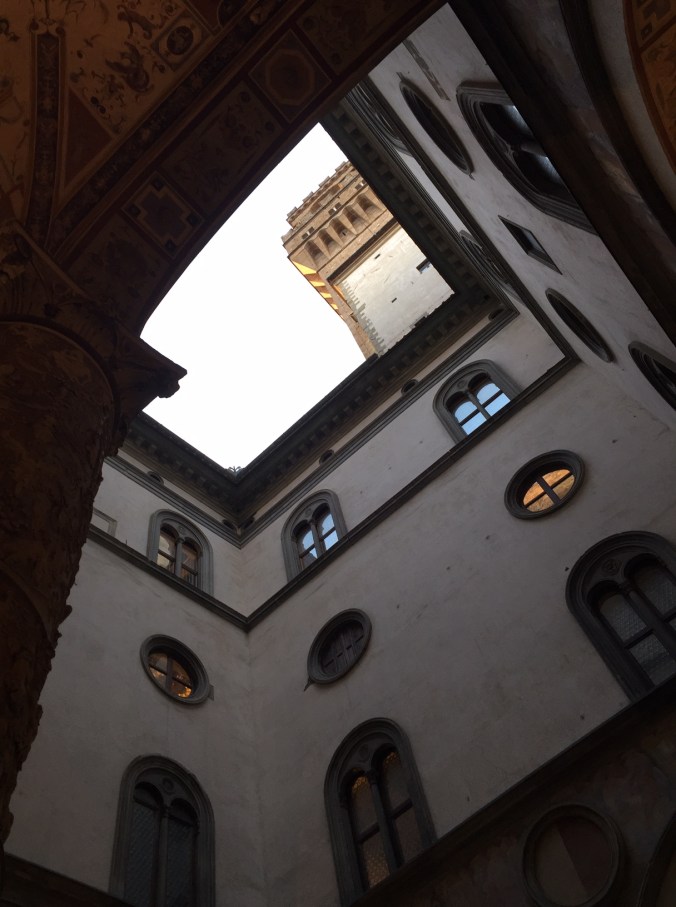

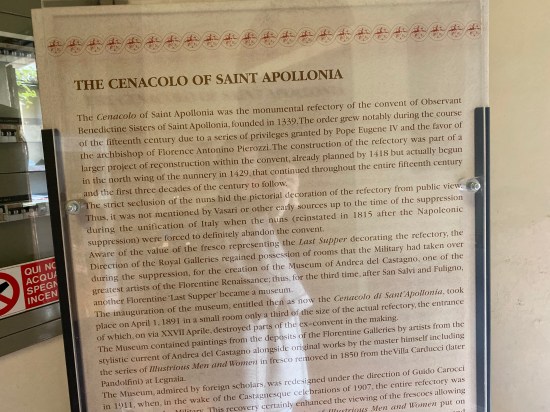

There are no lines at this former convent and no crowds. Few people even know to ring the bell at the nondescript door. What they’re missing is an entire wall covered with the vibrant colors of Andrea del Castagno‘s masterful Last Supper (c. 1450).

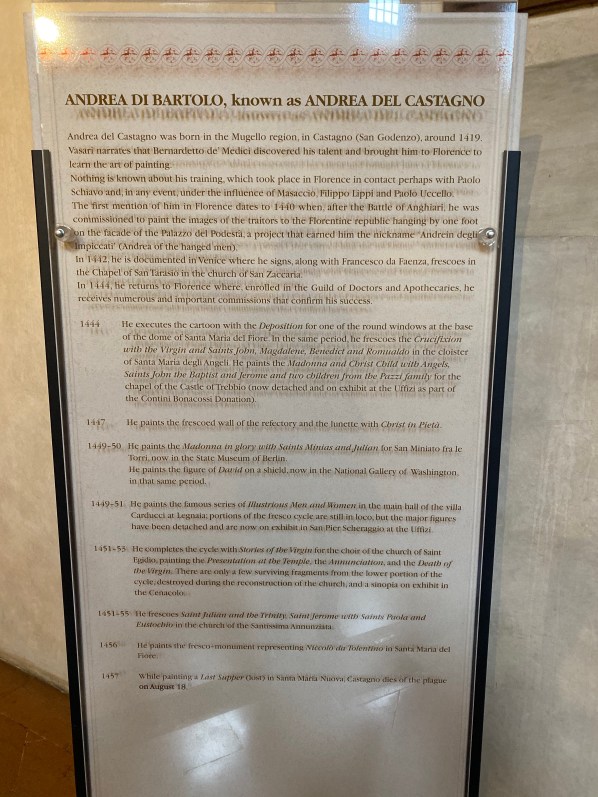

The end wall of the large refectory was decorated with frescoes, although these were never known to the outside world since the nuns were strictly cloistered. It was only with the suppression of the convent in 1860 that the existence of this masterful fresco of the Last Supper was revealed. Interestingly, it was initially attributed to Paolo Uccello, but then finally to the true painter, Andrea del Castagno (1421-1457).

Castagno created a richly colored composition, filled with interesting details. For one, the deeply colored “marble” panels fill the middle-ground register and the depiction of black and white ceiling tiles follow a strict linear perspective system. The long white tablecloth sets off only one figure: the darkly hued figure of Judas the Betrayer, whose face is painted to resemble a satyr, an ancient symbol of evil.

Another three frescoes were discovered above this one in the 1950s. Three scenes are represented: the Resurrection, the Crucifixion, and the Entombment of Christ. At the time of the restoration in 1952, the three frescoes were removed to be preserved, thus revealing the splendid sinopie that were painted over.

So, here’s the single sign that tells the observant visitor that something wonderful is kept within this sober facade.

Here is the experience of the refectory:

Some introductory information about the artist:

Yesterday I posted Part 1 of this subject. That post grew to a length that I decided to keep these many pictures of the Chiostro as a separate post.

Once upon a time in Florence, there was a small oratory (church) dedicated to the Compagnia dei Disciplinati di San Giovanni Battista (Confraternity of St. John the Baptist), a group founded in 1376.

The tiny facade of the Cloister of the Scalzo in Florence, on present day Via Cavour, was built as the entrance to that now-destroyed church. Buildings that served the Confraternity were called “dello Scalzo” because the cross-bearers in the Confraternity’s processions walked with bare feet as a sign of humility, and scalzo means barefoot.

The brothers belonging to the Confraternita dressed in long, simple, black robes with a cowl. Their garb is depicted in the della Robbia style glazed-terracotta lunette above the entrance portal to the chiostro.

The emblem of the confraternity is the bust of Saint John the Baptist wearing a garment of camel hair with a leather belt around his waist. He is depicted with a halo and holds a golden cross. In the lunette over the entrance, the saint is in the center, with 2 brothers, one on either side. The saint was intentionally represented in a larger scale than the brothers, as a sign of of his relative importance.

The brotherhood lasted until 1786, when the property was sold. The small oratory was destroyed in the 19th century, to make way for the modern Via Cavour.

Fortunately for posterity and lovers of art in particular, the Chiostro was saved. The Accademia delle Belle Arti used it for a while, but it was opened to the public in 1891.

While the small cortile, designed by Giuliano da Sangallo, is a lovely little piece of Florentine Renaissance architecture in and of itself, with its harmonious proportions and lovely use of pietra serena, it is the fresco cycle on the four walls of the cloister that make it a must-see for any art lover.

This fresco cycle was painted by Andrea Del Sarto (Andrea Vannucchi, 1486-1530), and shows episodes from the Life of St. John the Baptist. With the 12 main scenes presented in large, horizontal frames, subdivided by grotesque style motifs, the beautiful cycle is complete. Unlike the more famous places in Florence, such as the Uffizi and the Accademia, one can visit the chiostro in a quiet and relaxed manner, and often have the entire venue to yourself. I highly recommend a visit to this exquisite, almost secret, gem.

Here, in all its quiet glory, is the cloister interior:

It is believed that Andrea del Sarto painted the entire cycle, including the paintings in the decorative bands, with one exception which will be discussed below.

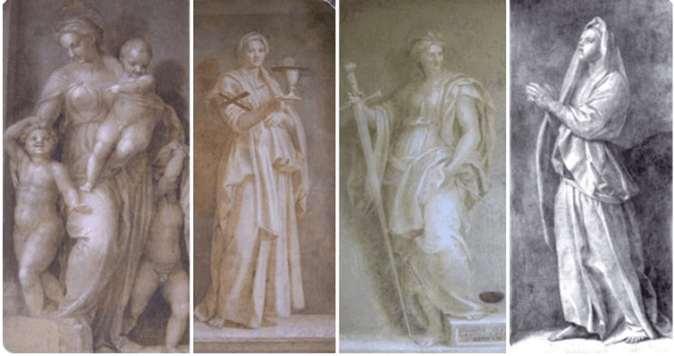

In addition to the large panels depicting the saint’s life, four tall, vertical paintings represent the Virtues on the sides of the 2 main axes: Charity (1513), Faith (1523), Justice (1525) and Hope (1523).

The 12 distinct moments from life of Saint John include his birth, the famous dance of Salomè, and the beheading of the saint. The scenes also include the baptism of Jesus and the preaching in the desert. Curiously, the sequence of the scenes is not presented in chronological order on the walls.

We know that the paintings were created over a relatively long period, from 1509-26. This is a bonus for the world of art history, for the stylistic evolution of Andrea del Sarto can be followed, starting with the Baptism of Christ, c. 1509-10. This painting bears the clear influence of the quattrocento Florentine masters.

Self Portrait, Andrea del Sarto

Self Portrait, Andrea del Sarto

The later scenes, painted when he had achieved his maturity as an artist, reveal the increasingly dynamic sculptural clarity of Andrea’s figures, which he borrowed from Michelangelo and which has the manneristic foreshadowings for which Andrea is noted. In The Capture of the Baptist painted in 1517, we see a more dynamic composition, probably inspired by the work of the very popular Michelangelo and other peers like Andrea’s friend, Franciabigio.

The frescoes painted in the decade of 1520 were made during Andrea del Sarto’s maturity, and we notice the much more solemn and majestic figures. Their heroic proportions run parallel with the era’s then dominant michelangiolismo.

The Baptism of the Multitudes, painted in a sumptuous almost Mannerist style, is both harmonious and complex: it is full of moving figures, many nude, and filled with pictorial virtuosity. This would inspire the entire next generation of artists.

Interestingly enough, Andrea del Sarto himself was a member of the Confraternity of St. John the Baptist and practiced a lifestyle based on the sober and spiritual edicts of the group. He was thus a direct messenger of the spiritual values of simplicity shared by his brothers, which is why, perhaps, this spartan approach of monochromatic frescoes were chosen. Certainly, these paintings were less expensive to paint than fresco decorations with gold leaf and precious color mineral pigments. I don’t know why the chiaroscuro palette was chosen; perhaps it was a combination of the two influences.

Not only was Andrea del Sarto a member of this confraternity, but he lived nearby of the current Via Gino Capponi and Via Giusti. You can see his house pinned in red on the map below. Note how close the Chiostro is, located on the upper left side of the map. They are about a 6 minute walk from each other.

The plaque below marks the former home of Andrea Del Sarto.

The coat-of-arms on the corner of the house in which Andrea lived tells us clearly that this section of town was part of Medici territory. It makes sense, the house and Chiostro are very near San Marco.

The photo below shows how close Andrea lived to the Duomo of Florence. He lived, like so many Renaissance artists, in its shadow.

Andrea reached extraordinary stylistic and technical skill and is important, as well, because he played an important role in the complex artistic events of Florence at the beginning of the 16th century. He also played a critical role now recognized as fundamental to the development of Mannerism.

Two of the scenes, the Departure of John the Baptist for the Desert, and the Blessing of the Baptist, were actually painted by the artist’s friend and collaborator, a man known as Franciabigio (Francesco di Cristofano, 1482-1525). Franciabigio was asked to paint these 2 panels because in 1518 Andrea was absent from Florence.

In fact, Andrea had been summoned by King François I to the French court at Fontainebleau. The king personally invited Andrea join the Fontainebleau school, for his fame of being the “faultless painter” (as Vasari would say) had gone beyond the borders of the Italian peninsula. The elegance and balance of Andrea’s figures were considered to have no match among any living painters.

However, Andrea returned to Florence a year or so later and finished the Cloister’s fresco cycle himself.

Admired by Michelangelo, Del Sarto was also teacher to Giorgio Vasari, who later became his biographer, describing him as the faultless painter or “painter without errors.” Del Sarto played an important role now acknowledged as fundamental to the development of Mannerism. Sarto’s style is marked throughout his career by an interest in the effects of color and atmosphere and by a sophisticated informality and natural expression of emotion.

Incidentally, the terracotta bust in the cloister represents bishop Saint Antonino Pierozzi who, as archbishop, sanctioned (in 1455) the birth of the Compagnia dello Scalzo. The Confraternity became increasingly more popular in Florence, as witnessed by an official document in 1631. The chronicles refer to a large community of brothers composed of a Governor, a council held by two elder brothers, an accountant, a copyist, six nurses, a dozen of specialized clerks, a priest, a doctor, and a servant.

The frescoes in the cloister were exposed to weather and thus deterioration for centuries. In the early 1960s, the frescoes were detached from the walls for restoration and were finally returned to the cloister to be reopened for public viewing in 2000.

Andrea del Sarto’s fresco cycle is certainly among the most important of Florentine painting of the early 16th century. Many experts consider this cycle to be his masterpiece.

http://www.polomusealetoscana.beniculturali.it/index.php?it/183/chiostro-dello-scalzo-firenze

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Chiostro_dello_Scalzo

Mary Shelley, wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley and author of Frankenstein, wrote of Brunelleschi’s Gates of Paradise in Florence: “Let us turn to the gates of the Battistero, worthy of Paradise. Here we view all that man can achieve of beautiful in sculpture, when his conceptions rise to the height of grace, majesty, and simplicity. Look at these, and a certain feeling of exalted delight will enter at your eyes and penetrate your heart.”

Jones, Ted. Florence and Tuscany: A Literary Guide for Travellers (The I.B.Tauris Literary Guides for Travellers) (pp. 24-25). I.B.Tauris. Kindle Edition.

When I first started visiting Florence in the late 1970s, the museum connected to the duomo was housed in a very old, smallish palazzo behind the duomo. About 4 years ago, the museum reopened after extensive renovations and it is one of the best museum spaces I’ve ever seen. It is state of the art and a must-see for anyone who values Renaissance art.

These are just a few samples.

I walk by this glorious church in Florence at least weekly and, if it happens to be open, I always wander through the interior, without really knowing why. It draws me like a magnet, but I’ve never really taken the time to really register what it holds, until yesterday when I had time to really savor the interior.

To really understand the church I start, as I always do, by reading. I discovered that this site was once just outside the ancient walls of Florence and the home of an original Carolingian oratory. Imagine, this very central locale at the heart of contemporary Florence was once outside the city walls.

That building was superseded in 1092 by a slightly larger complex of the Benedictine order of the monks; this order was created by a Florentine nobleman, Giovanni Gualberto.

Sidebar: The Story of Giovanni Gualberto: One Good Friday Giovanni Gualberto left home with his gang of roughs, fully intending to avenge the recent murder of his brother. Upon finding the murderer, who pleaded for his life and, because it was the very day Jesus was crucified, Gualberto decided to spare him. Gualberto went up to San Miniato, where a crucifix was said to have bowed its head to him in honor of his mercy. Gualberto later became a Benedictine monk and founded the Vallombrosan order. He died in 1073. This story is the source of Edward Burne-Jones's early painting The Merciful Knight, which shows Christ kissing Gualberto. The Crucifix of Saint Giovanni Gualberto, now kept in this church, is said to be the miraculous crucifix, but it isn't that old - the story is around 200 years older than this crucifix. A cult flourished in the late-14th and 15th centuries which ascribed to it miraculous powers).

When the Vallombrosan monks rebuilt the church, it was done in a simple Romanesque style that reflected the austerity of the order. By this time, new walls had been built (1172-75) to ring the growing city. Parish church status was granted to the church in 1178.

It was again rebuilt and expanded after 1250 in the Gothic style by Niccolò Pisano. Damage from the historic Florentine flood of 1333 resulted in more work on the church, possibly under the direction of Neri di Fioravante. This building period transformed the church into Gothic interior we see today. The inside is a large, dark space, even on bright days.

The understated and harmonious Mannerist façade of Santa Trinita was designed around 1593 by Bernardo Buontalenti, one of the main Mannerist artists in Tuscany, with sculpture by Giovanni Caccini. Buontalenti’s desire for a looming vertical effect led him to omit portions of the actual façade, leaving the odd bit to the sides.

Despite all the rebuildings, we are fortunate that we can still see a bit of the Romanesque medieval building. It is visible inside as you look at the “counter-facade” or back wall of the church’s original front.

A controversial ‘restoration to its original form’ in the 1890s led to the loss of many Mannerist elements, including a staircase in front of the high altar by Buontalenti of 1574 which is now in Santo Stefano al Ponte.

Sidebar: Buontalenti is said to have been inspired by shells and the wings of bats in designing this staircase. It was admired by Francesco Bocchi, writing in 1591, especially for it's bringing the clergy closer to the congregation. He also said that the church responds to the eye with considerable grace despite being planned at"a very uncouth time."

As stated above, the interior of the church is very much a 14th-century Gothic work, and is laid out in the form of an Egyptian cross. It is divided into three aisles separated by pilasters that rise up to gothic archways and a cross-vaulted ceiling.

During the restoration carried out following the 1966 flood the ’embellishments’ added in the early 1900s were stripped away, returning the frescos of the chapels to their original splendor.

The bas-relief over the central door of the Trinity was sculpted by Pietro Bernini and Giovanni Battista Caccini.

The 17th-century wooden doors have carved panels depicting Saints of the Vallumbrosan order.

The Column of Justice (Colonna di Giustizia) in the piazza, originates from the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, and was a gift to Cosimo I de’ Medici by Pope Pius IV. It was erected in 1565 to commemorate the Battle of Montemurlo in which Florence defeated Siena.

The Church of Santa Trinita belonged to the Strozzi family and later passed to the Medici family. The church was patronized over the centuries by many of Florence’s wealthiest families; as a result its many rebuildings allow it to serve as the text for a course on Italian art history.

Even though the Italian word for trinity is trinità, with an accent indicating stress on the last vowel, the Florentine pronunciation puts the stress on the first vowel, and the name is therefore writtenwithout an accent; sometimes, it is accented as trìnita to indicate the unusual pronunciation.

In this post, I’ll only discuss the art works that seem most important to me. A full accounting of the chapels would need a book.

The sacristy:

The sacristy entrance is to the left of the side door in the right transept. The entrance doorway (by Lorenzo Ghiberti), can be opened on request by the attendant. Originally the sacristy was the Strozzi Chapel, and thus it contains the tomb of Onofrio Strozzi, commissioned by his son Palla, designed by Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi.

On the altar used to stand the Adoration of the Magi by Gentile da Fabriano, now in the Uffizi Gallery and discussed below under the category of “lost works.” Onofrio Strozzi wanted a monument to commemorate Saint Onofrio and Saint Nicholas, which was made by Michelozzo.

Speaking of the Strozzi family, we should keep in mind that Palla Strozzi was banished after the revolt in 1434 against Cosimo il Vecchio. Palla was among the 500 who were banished and he died in Padua. Onofrio Strozzi’s tomb is decorated with flowers painted by Gentile da Fabriano.

To enter the sacristy, to the right, is to step back in time. Alhough Abbot Baldini had the entire church whitewashed “to display his love for it” in 1685, a number of early 14th-century frescoes survived, and were moved here during the restoration following the 1966 flood, including a Noli me Tangere (Jesus saying “Don’t hinder me” to the Magdalen as he leaves the tomb, generally mistranslated as “Don’t touch me”) by Puccio Capanna and a Crucifixion clearly based upon Giotto’s. The chapel also houses also a Pietà by Barbieri.

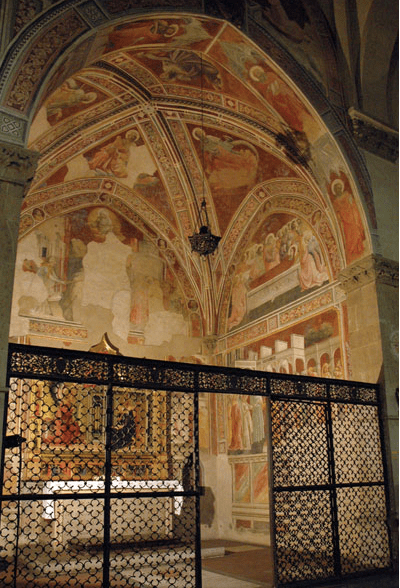

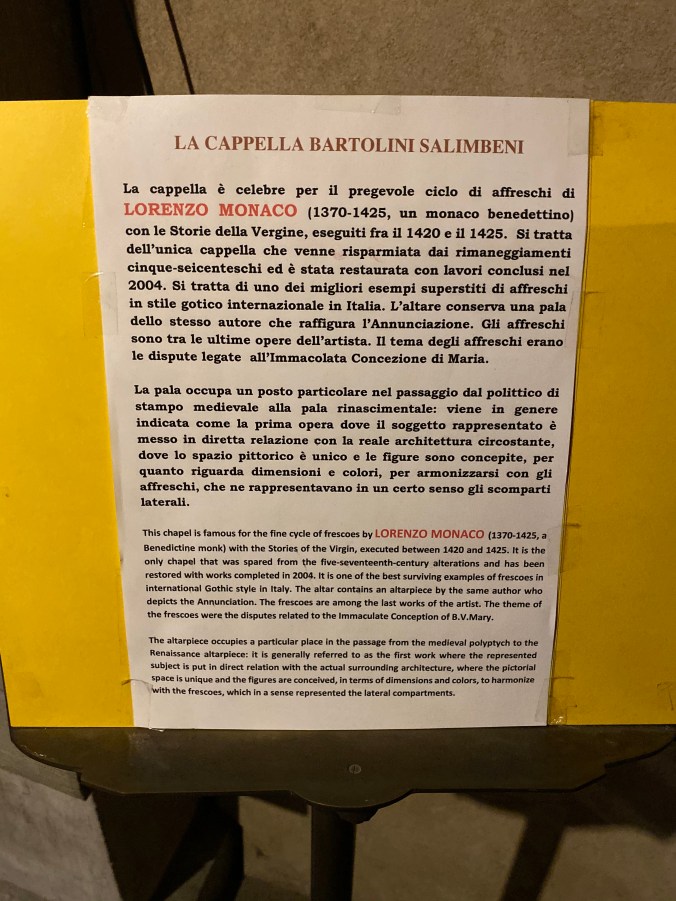

The Bartolini Salimbeni Chapel, with frescoes of The Life of the Virgin by Lorenzo Monaco, painted between 1420-25. These are his only known work in fresco and therefore very special. I love looking at the people on the right wall and the architecture on the left. The frescoes are one of the few surviving examples of International Gothic style frescoes in Italy.

The frescoes were commissioned by the Bartolini family. They covered the earlier fresco cycle by Spinello Aretino believed to have been commissioned by Bartolomeo Salimbeni in 1390.

The chapel, created during the Gothic renovation and enlargement of the church in the mid-13th century, was owned by the rich merchant family of the Bartolini-Salimbeni from at least 1363. Their residence, the Palazzo Bartolini Salimbeni, was located in the same square of the church.

Lorenzo Monaco’s frescoes date to 1420s, when a re-decoration program was carried on in the whole church, as testified also by fragments of Giovanni Toscani’s frescoes in the annexed Ardinghelli Chapel.

The Annunciation altarpiece is also by Lorenzo Monaco. This beautiful painting on wood is signed by the artist. He did great work at the convent of Santa Maria degli Angeli, but it is in this chapel where you can see his best work in an original context. The floor features poppies, the family emblem, and Per non dormire, their motto, which translates as ‘For those who don’t sleep.’

The frescoes, fragments of which are now lost, occupy the chapel’s walls, vault, arch and lunette. Lorenzo Monaco was mostly a miniaturist, and his (or his assistants’, since he was aged at the time and perhaps at his death in 1424 the work was unfinished) lack of confidence with the fresco technique is possibly shown by the presence of figures completed in different days, or the use of dry painting in some places.

Lorenzo Monaco’s was inspired by numerous contemporary examples of “Histories of the Virgin” cycles, such as the Baroncelli Chapel by Taddeo Gaddi; the Rinuccini Chapel by Giovanni da Milano and others; in the church of Santa Croce; Orcagna’s frescoes in Santa Maria Novella, the Holy Cingulum Chapel by Agnolo Gaddi in the Cathedral of Prato and the stained glasses of Orsanmichele, with which perhaps Lorenzo Monaco had collaborated.

The theme of the frescoes are connected to the contemporary dispute about the “Immaculate Conception of Mary;” i.e. the question of if she had been born without original sin. This was a major philosophical argument at the time and found the Franciscans and the Benedictines (including the Vallumbrosan Order holding the church at the time) against the Dominicans. Lorenzo Monaco’s frescoes were inspired by the apocryphal Gospel of James, dealing with Mary’s infancy and supporting the Vallumbrosan’s view that she had been not naturally born by her father.

The images in the chapel all depict scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary that specifically support the belief that Mary was not born by a human father, but immaculately. Instead of delving into doctrine, just know that at this time a feud was raging between the Dominican and Franciscan orders, and Mary’s Immaculate Conception was just one point of contention. The Vallumbrosians were Team Franciscan and Team Immaculate Conception. The chapel was thus supportive to the Franciscan brothers and unsupportive to the point of view of the Dominicans.

The cycle begins in the lunette on the left wall, portraying the Espulsion of Joachim from the Temple and the Annunciation to Joachim. Below are the Meeting of Joachim and Anne at the Golden Gate, set in a fancifully imagined Jerusalem with high tower, belfries and other edifices painted in pink.

The water of a stream where several youths are drinking is a symbol of Mary as the source of life, while the sea is a hint to her attribute as Stella Maris (“Star of the Sea”) and the islet a symbol of virginity. The stories continue in the middle part of the end wall, with the Nativity of the Virgin, following the same scheme of Pietro Lorenzetti’s Nativity of the Virgin, with Jesus bathing, and the Presentation of the Virgin at the Temple. The latter scene contains several numerology hints in the steps (three and seven, the number of the Theologic Virtues and all the Virtues respectively) and in the arches of Solomon’s Temple (three like the Holy Trinity).

The scene on the mid-left wall, perhaps the sole executed by Lorenzo Monaco alone, depicts the Marriage of the Virgin. The rejected suitors walk from the right to left; one of them (that in the background, behind the arcade) is a possible self-portrait of Lorenzo Monaco, although his age does not correspond to the artist’s one at the time. The next scene is that of the Annunciation, whose predella has scenes of the Visitation, Nativity and Annunciation to the Shepherds, Adoration of the Magi and the Flight into Egypt.

The next episodes in the frescoes include some miracles connected to Mary: the Dormitio, the Assumption, and the Miracle of the Snow. In the cross vault are portrayals of Prophets David, Isaiah, Malachi and Micah.

The frescoes were covered with white plaster in 1740, and were only rediscovered in 1885-1887 by Augusto Burchi. In 1944, the German invasion forces blew up the nearby Ponte Santa Trinita, causing damages also to the frescoes. They were restored in 1961 and again in 2004.

Above all, this chapel is interesting because Lorenzo mixes styles with a surprisingly result. The Annunciation at the altar is done in the High Gothic style, with stylized figures rather convincingly rendered, set against an equally stylized background. The frescoes on the walls, however, reveal that Lorenzo was well aware of the new developments in painting introduced by Masaccio: he displays a firm grasp of the newly emerging Renaissance style, painting natural looking people who are solidly anchored to their backgrounds.

The Compagni Family Chapel, was dedicated to Saint John Gualberto. We will remember that John Gualberto was the Florentine who founded the Vallumbrosan order, for whom this church served. The chapel’s walls were once frescoed with scenes from the life of this saint. The remaining scenes are high up on the outer arches and show The Murder of St. John Gualberto’s Brother and St. John Gualberto Forgiving the Assassin. Some sources say they are by Neri di Bicci and his father, Bicci di Lorenzo, but they have recently been attributed to Bonaiuto di Giovanni, an associate of Bicci di Lorenzo.

The Spini Chapel is notable for the wooden statue of the Penitent Magdalene, dressed in hair cloth, begun by Desiderio da Settignano and finished by Benedetto da Maiano, in about 1464. It is almost impossible not to compare this work with Donatello’s Mary Magdalene in the Opera del Duomo in Florence. Most likely, Desiderio was inspired by the master.

The Saint John Gualberto Chapel commemorates the founder of the Vallombrosan Order whose relics are preserved here. It was built as a gift to the church by the monks, and it was designed and created to look like a real yet small casket. Frescoes were painted by Passignano at the end of the 1500s.

The Scali Chapel houses a monument to Berozzo Federighi by Luca della Robbia. Federighi was the Bishop of Fiesole who died in 1450; the monument was created by Luca della Robbia in 1454. The monument’s frame is made of majolica using the opus sectile technique: every oval is made of small tiles that create a mosaic (it’s one of the first examples of the use of majolica for funerary monuments).

The monument was moved here from the deconsecrated church of San Pancrazio in 1896.

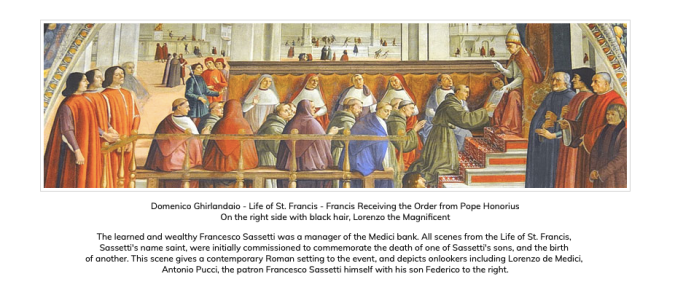

The Sassetti Chapel is the most famous part of the entire church, filled with a gorgeous cycle of frescoes by Domenico Ghirlandaio’s, depicting scenes from the Life of St Francis.

The Sassetti Chapel is the crown jewel of Santa Trinità and often considered to be Domenico Ghirlandaio’s capolavoro.

Aside from its beauty, the chapel tells us so much about life in Renaissance Florence. Francesco Sassetti, a banker for the Medici, obviously had a lot of money. Like any wealthy family of the time, he used his wealth to acquire and decorate a family chapel around the year 1483.

Initially he planned to build his chapel in Santa Maria Novella, but the Dominicans turned him down when they discovered that Sassetti planned to include scenes from the life of the Dominican’s nemesis, St. Francis, decorating the walls. The Vallumbrosians of Santa Trinita, on the other hand, gladly welcomed Sassetti’s petition, thrilled to have the hand of the most prominent artist in Florence at the time, Dominicao Ghirlandaio, decorating their church.

The chapel’s primary function is the burial place for Francesco and his wife Nora Orsi (the two are seen kneeling on either side of the altarpiece). The chapel also became a sort of family photo album as all of the Sassetti children are depicted in the frescoes. Additionally, the chapel served as a humanist who’s who, as it features images of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Poliziano, Costanzo, and even Ghirlandaio himself.

Ghirlandaio also used the chapel to reinforce the emerging Renaissance trend that Florence was the new Rome. He depicts events we know occurred in Rome and sets them in Florence, and in almost every scene we spy notable Florentine landmarks, such as the Duomo and the Palazzo Vecchio.

The Sassetti chapel alone makes a visit to Santa Trinita more than worthwhile and is a celebration of both Saint Francis and of Renaissance art Florence in general. This cycle of frescoes is a high-water mark for painting in 15th century Florence.

In the center is an altarpiece depicting The Adoration by the Shepherds. It dates to 1585 and is signed by Ghirlandaio, as are all of the frescoes in the chapel. This altarpiece is often cited as the work most obviously inspired by the Portinari Altarpiece, especially the shepherds. Ghirlandaio depicted himself as the shepherd pointing to the Baby and the carved garland (ghirlanda) on a sarcophagus. The unusual presence of this antique sarcophagus in a nativity has been explained as it’s thereby making a group of three with the actual tombs of the donors flanking the altarpiece in the side walls.

The altarpiece is quite important, not the least because Ghirlandaio included classical elements, such as the sarcophagus manger and the Corinthian columns holding up the roof of the shack (one is dated 1485), and based the poses of the shepherds on those of the Flemish master Van der Goes’s triptych (now in the Uffizi). This reveals the presence of the newly awakened interest in the Classical world that was one of the characteristics of the High Renaissance, and also get an idea of the impact the Flemish style had upon the great masters.

It’s always so interesting to me to see the clothing; through it, we get to view the way Florentines dressed at the time.

In another scene, we can see contemporary Florence: you can make out Piazza Signoria and the Loggia dei Lanzi. There are no statues in the loggia, however, for those were added later. In this scene Lorenzo il Magnifico and his sons, Piero, Giovanni, and Giuliano climb the steps with their tutors, led by humanist scholar Agnolo Poliziano.

Everyone’s favorite scene is in the fresco panel just above the altarpiece. In the center, we see a young boy sitting at prayer on a bed. According to the story, the poor boy had fallen from the top of the Palazzo Spini, which is just across the piazza from this church (and home to the Ferragamo empire now). This was an actual event that had happened in Florence and had horrified the local population. Luckily, St. Francis–who himself had already died–was able to perform a (posthumous) miracle by bringing the boy back to life. (It is also said to allude to the death of Sassetti’s first son Teodoro and the birth of his second, given the same name as a sort of resurrection.)

According to the literature, this popular scene was a late replacement by Ghirlandaio for a depiction of the Apparition at Arles, which he had originally planned for this space.

The women clustering to the left said to be Sassetti’s daughters. It is said that the whole cycle contains about 60 of the Sassetti family and friends. The figure far right, with his hand on his hip, is said to be Ghirlandaio.

This was supposed to be one of St. Francis' posthumous miracles.Don'tyou love the Catholic Church and its understanding of the passage of time and the supernatural feats of its chosen few? You have got to admire the ingenuity, if nothing else! Never let the death of a sain stop him from performing miracles.

Because this event happened in Piazza Santa Trinita, Ghirlandaio shows us how the square appeared at that time, including the very church in which we are standing, Santa Trinita, as it appeared before the later addition of Buontalenti’s façade. Sassetti’s children fall to their knees (on the left); note the old Romanesque façade and Ponte Santa Trinita as it was before the great flood of 1557.

The Confirmation of the Rule scene above features portraits of Lorenzo de’ Medici with his sons and their tutor, Angelo Poliziano, against the backdrop of the Piazza della Signoria. (Despite the Florentine setting, this event in fact took place in Rome.)

The four Sibyls in the vaults (including one said to have been modeled on Sassetti’s daughter, Sibilla) are also by Ghirlandaio, as is the David and the Tiburtine Sybil telling Augustus of the birth of the Redeemer (Vision of Augustus) on the wall above the chapel entrance.

We should remember that Francesco Sassetti was a Medici banker and it was he who was blamed for the declining fortunes of the Medici, just prior to his death from a stroke in 1490. He and his wife, Nera Corsi, kneel on either side of the equally gorgeous altarpiece. I love the inscription under the donor portraits: December 25, 1480.

On the left wall, Saint Francis dons his habit, and on the right, in a fresco attributed to Domenico’s brother Davide, he undergoes a trial by fire before the Sultan (Francis went on a crusade and returned horrified by what he’d seen).

The next level down, to the left he receives the Stigmata before a realistic representation of the Santuario della Verna, an abbey in the wild mountains between Florence and Arezzo.The Saint’s death is to the right. Francesco Sassetti and his wife, Nera Corsi, are in the tombs, and are also shown kneeling facing the altar.

While a visit to Santa Trinita will repay you a thousand fold with art, now we turn to the works created for this magnificent church but have been removed from it.

The Cimabue Maestà della Madonna, painted around 1280 for the high altar here, is now in the Uffizi Gallery. It was replaced with a Trinity by Alesso Baldovinetti in 1471 and moved into a side chapel and, later, to the monastery infirmary. It’s been in the Uffizi since 1919, where it’s now part of the spectacular Cimabue/Giotto/Duccio trio on display in room 2.

An altarpiece signed and dated May 1423 by Gentile da Fabriano, was commissioned by Palla Strozzi around 1421 for the family chapel here in the sacristy. The gilt and gorgeous central panel, The Adoration of the Magi, and two panels of the predella, The Nativity and The Flight into Egypt, are in the original frame in the Uffizi (since 1919). Another panel from the predella, the impressively architectural and very finely-wrought Presentation at the Temple, is in the Louvre (since 1812), with a copy taking its place in the Uffizi.

There is conjecture that the Presentation panel may feature a building based on the long-lost Strozzi palazzo which stood opposite this church. The main panel is said to contain a portrait of Palla Strozzi in the train of the magi, holding a hawk.

Also commissioned by Palla Strozzi for the same chapel here was A Deposition by Fra Angelico now in the Museo di San Marco. The altarpiece was begun by Lorenzo Monaco; its pinnacles are by him, as are what are thought to be the predella panels of scenes from the lives of Saints Onofrio and Nicholas, now in the Accademia.

The altarpiece had been begun by Lorenzo, but upon his death in 1424 it was completed by Angelico and installed on 26th July 1432. Palla Strozzi is depicted on the right holding the crown of thorns and the nails, his son Lorenzo kneels in the right foreground nearby. A highly finished drawing of The Dead Christ from the altarpiece is in the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge.

Bicci di Lorenzo’s altarpiece of 1434, painted for the Compagni chapel here (see reconstruction above, from Bicci di Lorenzo’s altarpiece for the Compagni family chapel by Dillian Gordon, Burlington Magazine Feb 2019 ) has its main-tier panels now in Westminster Abbey in London. The central panels show the Virgin Enthroned with Saints John Gualberto, Anthony, John the Baptist and Catherine. The predella panels have in recent years been identified as the central Nativity and Saint John Gualberto and the Destruction of the Abbey of Moscheta in private collections, and the Baptism of Christ in the York Art Gallery.

The missing panels are also thought to be scenes from the lives of the saints above them, Anthony and Catherine. The reasons for the altarpiece’s removal, by 1845, are unknown.

Bicci’s son Neri di Bicci painted an altarpiece of The Assumption in 1455/6 for the Spini chapel here. It is now in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottowa.

The striking Trinity with Saints Benedict and Giovanni Gualberto by Alesso Baldovinetti of 1469-71, originally from the Gianfigliazzi chapel here, is now in the Accademia too.

Albertinelli and Franciabigio’s impressive Virgin and Child between Saints Jerome and Zenobius painted for the Zenobi del Maestro chapel here, is now in the Louvre, having been looted by Napoleon.

Bronzino’s early major work, The Dead Christ with the Virgin and Mary Magdalene of c. 1528-29, formerly in the convent here, has been in the Uffizi since 1925.

You must be logged in to post a comment.