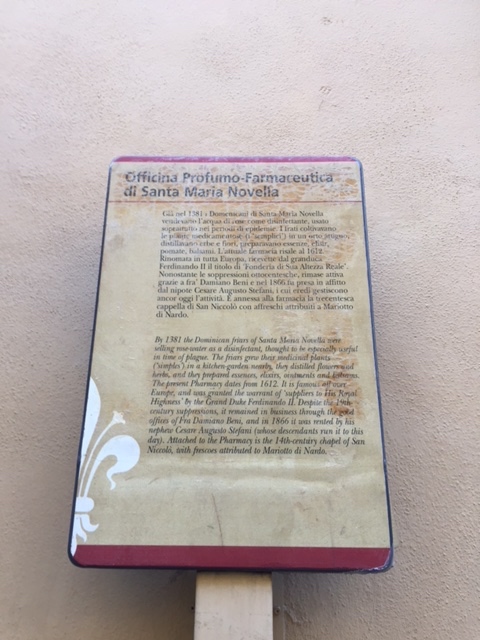

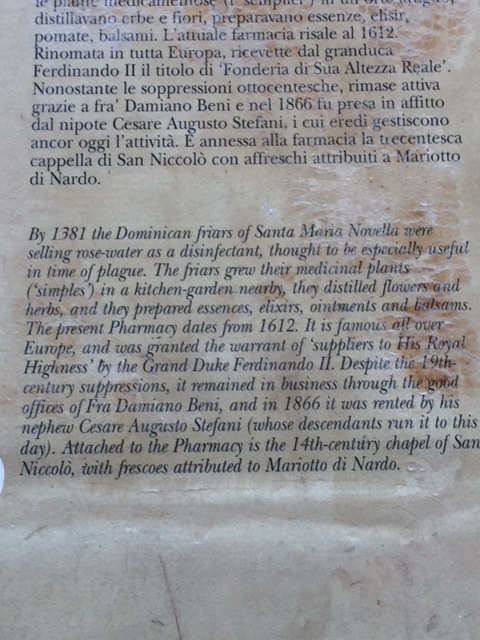

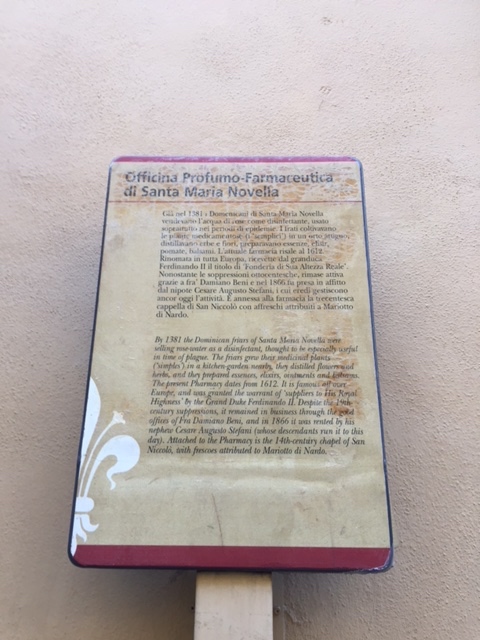

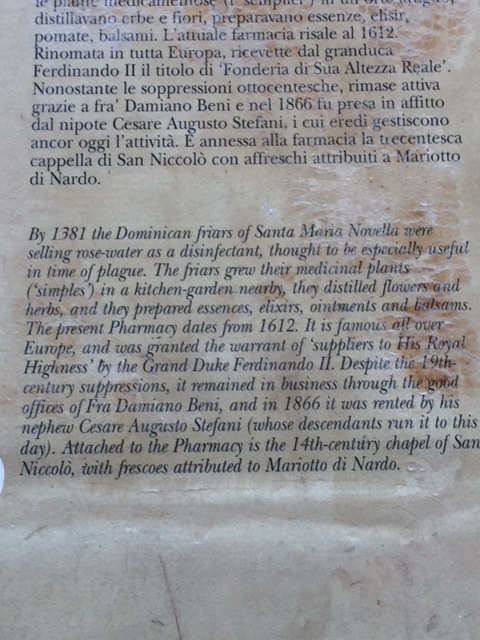

One of the world’s oldest pharmacies and a great place to visit!

One of the world’s oldest pharmacies and a great place to visit!

…when it comes to being an art museum professional!

Modigliani paintings in Genoa exhibition “crude fakes!”

For more, see this article: http://www.corriere.it/english/18_gennaio_10/modigliani-paintings-genoa-exhibition-crude-fakes-b1264e62-f61a-11e7-9b06-fe054c3be5b2.shtml

The blog post below is a good one on the subject of the Carrara marble quarries. If you would like to see the pictures, you can find the post here: https://livingwithabroadintuscany.blogspot.it/2012/04/going-inside-marble-mountains-of.html

| Everybody who drives or takes the train along the west coast of Italy has seen them from a distance. Anybody who has read The Agony and the Ecstasy has read about them. The white marble mountains of Carrara are interesting from afar—many people mistake the shining white marble for snow—but up close they are truly amazing. And there is no better way to see them than by going up the steep, unpaved roads in a 4×4 vehicle to drive right into the quarries, indeed right inside the mountains themselves. |

Lucy and I, along with friends Steve and Patti, have booked an excursion with Cave di Marmo Tours, which takes us on a three-hour excursion into the heart of the land where Michelangelo came to select the marble slabs he used to create his masterful sculptures. The mountains above Carrara are basically one huge block of crystallized calcium carbonate, which originated during the Jurassic era. Marble is created when limestone crystallizes under extreme pressure and heat. Limestone itself is formed from layer upon layer of sea shells. Tectonic action first buries the limestone, squeezing it until it crystallizes before thrusting it upward to form mountains.

Our German-Italian guide Heike fearlessly drives us up rugged, rain-rutted service roads overlooking the marble quarries, the city of Carrara and numerous small islands in the Mediterranean. The ride reminds us of Disneyland, with the added thrill of knowing that we are not on a secure track and that the scenery was originally created by the hand of God rather than man. As we bounce and skid first up and then down the steep slopes, Lucy tries to close her eyes and think about something else, but Heike keeps pointing out sights to see and takes pleasure in the knowledge that her tour is thrilling on a variety of levels.

We learn that the Romans discovered marble here in 176 BC, which meant they no longer had to import it from other countries. They built a port at Luni and roads into the mountains. Then they faced the puzzle of where to find strong workers willing to wield mallets and chisels and endure extreme weather conditions while working year-around in dusty quarries? No problem. They were rulers of most of Europe, so they just took some hearty northern Europeans as slaves and put them to work in the quarries. Heike says you can still see many light-haired, blue-eyed Italians in Carrara who are descendants of these early quarrymen.

The first blocks were taken from the mountains to the sea by slave power alone. Later came oxen, then trains. Now huge front-end loaders and dump trucks are used. All of the methods made use of wheels, and the city’s motto is “My strength is in the wheel.”

Harvesting techniques have also changed. Marble contains natural pressure fractures, and early workers used chisels and wooden wedges to widen the fractures and break off slabs. Later, explosives were used, but this had to be carefully done to avoid fracturing the slabs. Hand saws have also been employed.

Current techniques use drills and a type of chain saw incorporating industrial diamonds fastened to a flexible cable. Holes are drilled in the marble and the chain inserted in one end and pulled out the other. Then the cable is looped around a pulley powered by an electric motor and run for hours at a time until a clean cut is made. All the while, water is running in the hole to cool the chain and minimize the dust.

Much of the work is now done inside the mountains so as not to disturb the terrain, and we are able to go inside to observe the process up close. It is difficult to describe the scene in words, and photos don’t do it justice as well. The walls and ceiling are flat, though not uniformly so, as some support pillars remain. It reminds me of being inside a large cathedral, but instead of being built by adding marble slabs, it is what remains after removing slabs from the center. Moisture drips from the ceiling, and the floor is covered with a quarter inch of wet marble powder. The workers spend most of their time monitoring and repositioning the saws. It is dark, damp and dirty work, but I’m sure it would be a dream job for the first slaves forced to do everything by human strength alone.

The 188 quarries are all privately owned by very wealthy families, Heike says. The country should be earning more income from this lucrative business, but the quarry owners still benefit from an ancient agreement they reached with the duchy of Modena. They agreed to provide Modena with the choicest marble, and the duchy agreed not to tax them. I’m not sure how this agreement survived to the modern age, but Heike suggests it has much to do with money, politics and corruption, which Italy has long been famous for, so we are inclined to believe her.

Toward the end of the tour, we travel through an old railway tunnel, and I have read that this tunnel is 400 meters long, 400 meters above sea level and has 400 meters of stone above it.

The Italian Alps and the Dolomites will experience some of the lowest temperatures of the winter in the next week and many domains will also see significant fresh snowfall. The heaviest snowfall will be above the Aosta Valley where Cervinia (1,520m) can expect up to 45cm of fresh powder. The resort already holds close to 4 metres of snow base beneath top station at 3,480m and when the visibility is decent the skiing is epic. However next week the daytime temperatures here will be far below 0ºC, -7ºC the average high at resort level, so skiers will need to bulk up thermal layers. Today in Cervinia all 15 lifts are open and skiing is on fresh and dry groomed snow at all elevations.

People have been visiting the caves of Monte Kronio since as far back as 8,000 years ago. They’ve left behind vessels from the Copper Age (early 6th to early 3rd millennium B.C.) as well as various sizes of ceramic storage jars, jugs and basins. In the deepest cavities of the mountain these artifacts sometimes lie with human skeletons.

One of the most puzzling of questions around this prehistoric site has been what those vessels contained. What substance was so precious it might mollify a deity or properly accompany dead chiefs and warriors on their trip to the underworld?

Using tiny samples, scraped from these ancient artifacts, the analysis of scientists revealed a surprising answer: wine. And that discovery has big implications for the story archaeologists tell about the people who lived in this time and place.

In November 2012, a team of expert geographers and speleologists ventured into the dangerous underground complex of Monte Kronio. They escorted archaeologists from the Superintendence of Agrigento, going down more than 300 feet to document artifacts and to take samples. The scientists scraped the inner walls of five ceramic vessels, removing about 100 mg (0.0035 ounces) of powder from each.

It was found that 4 of the 5 Copper Age large storage jars contained an organic residue. Two contained animal fats and another held plant residues, thanks to what was believed to be a semi-liquid kind of stew partially absorbed by the walls of the jars.

But the 4th jar held the greatest surprise: pure grape wine from 5,000 years ago, and these Monte Kronio samples are some of the oldest wines known so far for Europe and the Mediterranean region.

This is an incredible surprise, considering that the Southern Anatolia and Transcaucasian region were traditionally believed to be the cradle of grape domestication and early viticulture. Later studies used Neolithic ceramic samples from Georgia, and pushed back the discovery of traces of pure grape wine even further, to 6,000-5,800 B.C.

There are tremendous historical implications for how archaeologists can now understand Copper Age Sicilian cultures.

From an economic standpoint, the evidence of wine implies that people at this time and place were cultivating grapevines. Viticulture requires specific terrains, climates and irrigation systems.

Archaeologists hadn’t, up to this point, included all these agricultural strategies in their theories about settlement patterns in these Copper Age Sicilian communities. It looks like researchers need to more deeply consider ways these people might have transformed the landscapes where they lived.

The discovery of wine from this time period has an even bigger impact on what archaeologists knew about commerce and the trade of goods across the whole Mediterranean at this time. For instance, Sicily completely lacks metal ores. But the discovery of little copper artifacts – things like daggers, chisels and pins had been found at several sites – shows that Sicilians somehow developed metallurgy by the Copper Age.

The traditional explanation has been that Sicily engaged in an embryonic commercial relationship with people in the Aegean, especially with the northwestern regions of the Peloponnese. But that doesn’t really make a lot of sense because the Sicilian communities didn’t have much of anything to offer in exchange for the metals. The lure of wine, though, might have been what brought the Aegeans to Sicily, especially if other settlements hadn’t come this far in viticulture yet.

Wine has been known as a magical substance since its appearances in Homeric tales. As red as blood, it had the unique power to bring euphoria and an altered state of consciousness and perception.

All of this is taken from https://www.thelocal.it/20180215/prehistoric-wine-italy-inaccessible-caves-rethink-ancient-sicilian-culture

![]()

Did you ever wonder who first said “When in Rome, do as the Romans do?” The following source explains: http://www.italiannotebook.com/local-interest/origin-do-as-romans-do/

Do you know the expression’s origin? St. Ambrose, way back in 387 A.D.

As the story goes, when St. Augustine arrived in Milan to assume his role as Professor of Rhetoric for the Imperial Court, he observed that the Church did not fast on Saturdays as it did in Rome.

Confused, Agostino consulted with the wiser and older Ambrogio (Ambrose), then the Bishop of Milan, who replied: “When I am at Rome, I fast on Saturday; when I am at Milan I do not. Follow the custom of the Church where you are.”

In 1621, British author Robert Burton, in his classic writing Anatomy of Melancholy, edited St. Ambrose’s remark to read: “When they are at Rome, they do there as they see done.”

Down through the years, Burton’s turn of the St. Ambrose quote was further edited, anonymously, into what is widely repeated today on a daily basis by some traveler, somewhere, trying to adjust to his/her new or temporary surroundings.

What does the dog say? Abbaia! of course!

You must be logged in to post a comment.