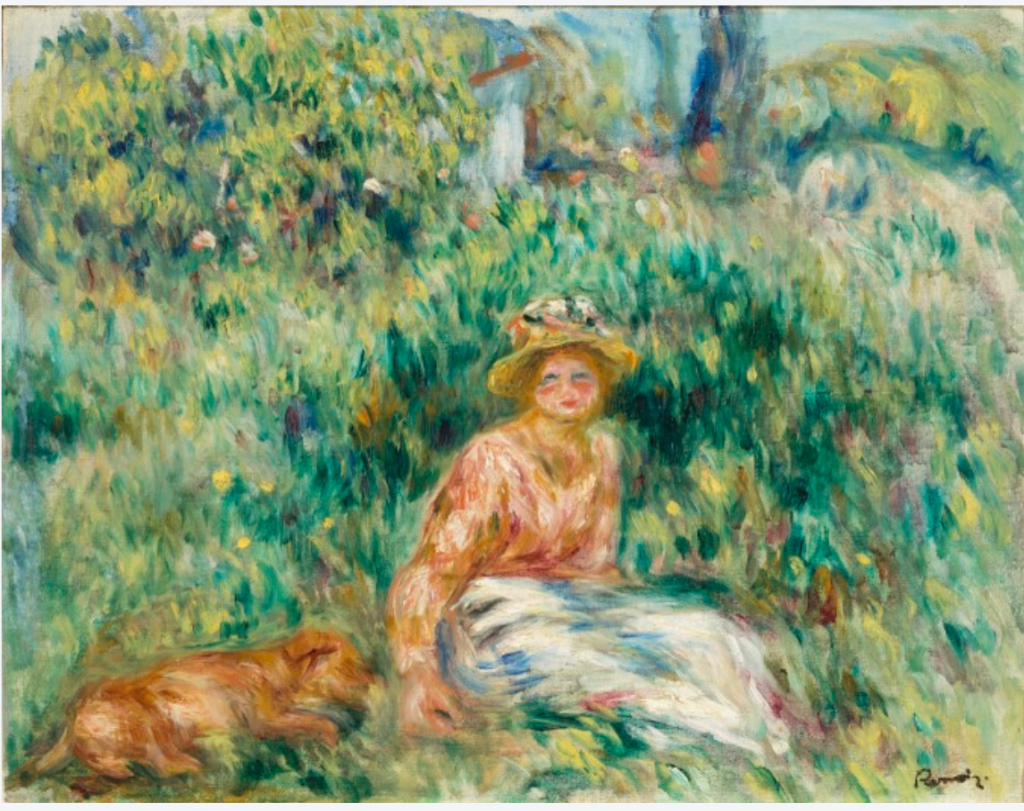

Another Renoir also at the DAM:

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Edmond Renoir, 1888. Oil paint on canvas; 22 3/8 × 19 1/8 in. Funds from Helen Dill bequest, 1937.4

Another Renoir also at the DAM:

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Edmond Renoir, 1888. Oil paint on canvas; 22 3/8 × 19 1/8 in. Funds from Helen Dill bequest, 1937.4

On loan to Denver Art Museum.

Benjamin West is a fascinating figure in American art history. He was born in 1738 in Pennsylvania, in a house that is now in the borough of Swarthmore on the campus of Swarthmore College. He was the tenth child of an innkeeper, John West, and his wife, Sarah Searson. The family later moved to Newtown Square, Pennsylvania, where his father was the proprietor of the Square Tavern, still standing in that town.

West told the novelist John Galt, with whom, late in his life, he collaborated on a memoir, The Life and Studies of Benjamin West, that, when he was a child, Native Americans showed him how to make paint by mixing some clay from the river bank with bear grease in a pot. West was an autodidact; while excelling at the arts, “he had little [formal] education and, even when president of the Royal Academy, could scarcely spell”. One day, his mother left him alone with his little sister Sally. Benjamin discovered some bottles of ink and began to paint Sally’s portrait. When his mother came home, she noticed the painting, picked it up and said, “Why, it’s Sally!”, and kissed him. Later, he noted, “My mother’s kiss made me a painter”.

From these simple origins, he went on to become a major figure in British art history, of which the painting on loan in Denver is a representative.

From 1746 to 1759, West worked in Pennsylvania, mostly painting portraits. While West was in Lancaster in 1756, his patron, a gunsmith named William Henry, encouraged him to paint a Death of Socrates based on an engraving in Charles Rollin’s Ancient History. His resulting composition, which significantly differs from the source, has been called “the most ambitious and interesting painting produced in colonial America”.

Dr William Smith, then the provost of the College of Philadelphia, saw the painting in Henry’s house and decided to become West’s patron, offering him education and, more importantly, connections with wealthy and politically connected Pennsylvanians. During this time West met John Wollaston, a famous painter who had immigrated from London. West learned Wollaston’s techniques for painting the shimmer of silk and satin, and also adopted some of “his mannerisms, the most prominent of which was to give all his subjects large almond-shaped eyes, which clients thought very chic”.

West was a close friend of Benjamin Franklin, whose portrait he painted. Franklin was the godfather of West’s second son, Benjamin.

Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky, c. 1816, now housed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art

In 1760 West went abroad, first to Italy. Sponsored by Dr. Smith and William Allen, then reputed to be the wealthiest man in Philadelphia, West traveled to Italy in 1760 in the company of the Scot William Patoun, a painter who later became an art collector. In common with many artists, architects, and lovers of the fine arts at that time he conducted a Grand Tour. West expanded his repertoire by copying works of Italian painters such as Titian and Raphael direct from the originals. In Rome he met a number of international neo-classical artists including German-born Anton Rafael Mengs, Scottish Gavin Hamilton, and Austrian Angelica Kauffman.

In August 1763, West arrived in England, on what he initially intended as a visit on his way back to America. In fact, he never returned to America. He stayed for a month at Bath with William Allen, who was also in the country, and visited his half-brother Thomas West at Reading at the urging of his father. In London he was introduced to Richard Wilson and his student Joshua Reynolds. He moved into a house in Bedford Street, Covent Garden. The first picture he painted in England, Angelica and Medora, along with a portrait of General Robert Monckton, and his Cymon and Iphigenia, painted in Rome, were shown at the exhibition in Spring Gardens in 1764.

In 1765, he married Elizabeth Shewell, an American he met in Philadelphia.

Dr Markham, then Headmaster of Westminster School, introduced West to Samuel Johnson, Edmund Burke, Thomas Newton, Bishop of Bristol, James Johnson, Bishop of Worcester, and Robert Hay Drummond, Archbishop of York. All three prelates commissioned work from him. In 1766 West proposed a scheme to decorate St Paul’s Cathedral with paintings. It was rejected by the Bishop of London, but his idea of painting an altarpiece for St Stephen Walbrook was accepted. At around this time he also received acclaim for his classical subjects, such as Orestes and Pylades and The Continence of Scipio.

West was known in England as the “American Raphael.” His Raphaelesque painting of Archangel Michael Binding the Devil is in the collection of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Drummond tried to raise subscriptions to fund an annuity for West, so that he could give up portraiture and devote himself entirely to more ambitious compositions. Having failed in this, he tried—with greater success—to convince King George III to patronise West. West was soon on good terms with the king, and the two men conducted long discussions on the state of art in England, including the idea of the establishment of a Royal Academy. The academy came into being in 1768, with West one of the primary leaders of an opposition group formed out of the existing Society of Artists of Great Britain; Joshua Reynolds was its first president.

West painted around sixty pictures for George III between 1768 and 1801. From 1772 he was described in Royal Academy catalogues as “Historical Painter to the King” and from 1780 he received an annual stipend from the King of £100. In the 1780s he gave drawing lessons to the Princesses and in 1791 he succeeded Richard Dalton as Surveyor of the King’s Pictures.

Between 1776 and 1778 George III commissioned as set of five double or group portraits of his family to hang together in the King’s Closet at St James’s Palace. His Queen and twelve of his children are included in the arrangement (two appear twice); every portrait is filled with action, instruction and affection, making them seem almost like extended versions of the conversation pieces commissioned by George III’s parents. In this double portrait the Queen and the Princess Royal are engaged in tatting a piece of material or embroidery between them; on the table beside the Queen is a bust of Minerva, a sheet of music and papers; in the distance are St James’s Park and Westminster Abbey. As if all this were not improving enough there is a sheet of drawings by Raphael. West was paid 150 guineas for this painting which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1777.

We don’t know who painted Three Young Girls; however, we do know that it was created between 1610 and 1620, and that it was painted in the style of William Larkin. William Larkin was an English artist who painted some of the most fashionable figures of his time. Until he was definitively identified in the 1900s, Larkin was simply known as the “curtain master” for his characteristic inclusion of curtains to frame the figures in his portraits.

Since Larkin was an active and very popular artist during the early 1600s, it seems likely that the anonymous painter of Three Young Girls purposely emulated Larkin’s distinctive style to please his patrons. Some features of Larkin’s style visible in this painting include strong lighting, polished treatment of flesh, and close attention to the details of rich fabrics, jewelry, and oriental carpets.

Three Young Girls was painted during what is known as the Jacobean period in England (1603-1625). This period corresponds to the rule of James I, son of Mary, Queen of Scots. Jacobean portraits are characterized by brilliant, jewel-like color and heavily decorated figures. Every detail of jewelry and fabric is meticulously delineated and recorded.

The girls’ matching earrings depict hunting-horns, or bugle-horns. These horns are a common motif in families’ coats of arms. Having a coat of arms was a symbol of status during this time because they had to be confirmed or granted by the king’s heralds. The hunting-horn motif suggests that the girls’ family were landowners and possibly members of the nobility or gentry (one class below the nobility).

The gold ring the middle girl wears could be either an engagement or a mourning ring. It’s possible that she had already become engaged and wears the symbol of her betrothal. At this time, stringing jewelry on black ribbon was popular. It’s also possible this ring belonged to the girl’s mother and she wears it as a symbol of mourning for her mother’s death.

The three unidentified girls in this painting are a mystery, but by carefully studying the details in the piece, we can learn several things about them. The girls are dressed in matching outfits, a sort of fashionable family uniform. Since fashions go in and out of style, the clothing worn by the figures helps us identify time period and status. The low necklines, lace collars, high waistlines, and yellow lace date the painting to somewhere around 1620. The expensive fabrics and gold, diamond, and coral jewelry the girls wear make it clear that they come from a wealthy family.

Certain details in this painting lead some art historians to theorize that it was painted after the death of the girls’ mother. The gold ring attached to a black string on the hand of the middle girl is one detail that could support this hypothesis. In addition to symbolizing an engagement, rings were used in the 1600s to symbolize mourning. The ring could have belonged to the girl’s mother, hence the large size, and she wears it in remembrance. The youngest girl’s “lady” or “fashion” doll is another clue that supports this theory. The doll is dressed in clothes that represent the style of clothing their mother would have worn. The black fabric of her dress, traditionally the color of death, would then be appropriate. The marigold, blue hyacinth, and periwinkle flowers the two youngest girls wear in their hair can represent, among other things, grief, despair, death, and mourning.

The red and yellow coral bracelets the oldest and youngest girls wear not only reaffirm their wealthy origins but may have been intended as powerful talismans (objects believed to have special powers). Coral beads were talismans of safety and good health, especially for children. Child mortality was high during this time, so perhaps these young girls were given coral to protect them from bad luck, illness, and death.

The Fruit: Traditionally in art, ripe fruit has represented fertility. However, the fruit held by the oldest and middle girls are only semi-ripe; they could be symbols of the girls’ immaturity and a suggestion of physical development in the future. In that light, the grapes and the pears may be symbols of the sisters’ future roles as mothers and wives. Grapes are symbolic of good luck. The pear is a celebration of a woman’s form.

The Flowers: The two youngest girls have marigolds, blue hyacinths, and blue-purple periwinkles in their hair; the eldest wears a red carnation. Although each flower has many meanings, marigolds traditionally symbolize affection and obedience; carnations symbolize betrothal; blue hyacinth, grief and mourning; and periwinkle, many things, from death to immortality to lovemaking. Although the individual flowers can be associated with love, affection, virginity, constancy, and marriage (all perhaps appropriate for a painting of young girls), they can all also represent grief, despair, death, and mourning.

Red, yellow, and green are the dominant colors in this painting. The artist probably chose these colors to make the painting vibrant and intense. The red can primarily be found in the dresses and the girls’ skin; the yellow in the lace, braiding, and ribbons on their dresses; and the green in the heavy drapes gathered behind the girls in the background.

The girls stand in a row holding each others’ hands and arms, indicating they have a close relationship. Their dresses and jewelry are identical and their headdresses are very similar. Each girl wears her hair in the same style, and they all have the same blue-gray eyes, red lips, pale skin, rosy cheeks, and long, slender noses.

The info above and more can be found at https://www.denverartmuseum.org/en/edu/object/three-young-girls

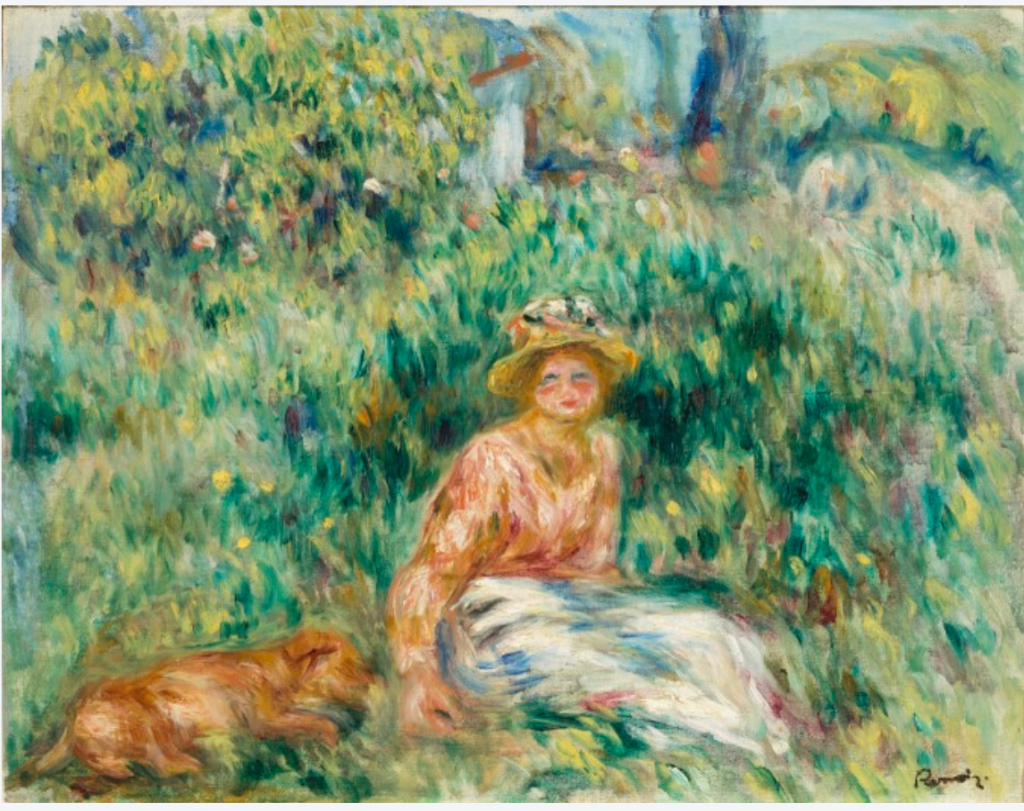

There’s an Italian painting at the Denver Art Museum that is one of my favorites in the world! Part of the reason it holds such a sweet spot in my heart is that when I was an undergraduate student at the University of Denver and first discovering Italian art, I chose this painting from all the works at the museum on which to write my first art history term paper. I got a nice grade for my effort and I remember the time of year (December) and subject matter (Adoration of the Magi) so well.

Here it is, in all of its Italian glory!

Adoration of the Magi, c. 1445-50

Bonifacio Bembo, Italian, 1420-1478

Born: Cremona, Italy

Active Years: 1455-1478

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bonifacio_Bembo

The Simon Guggenheim Memorial Collection

How this painting came to join the department of European and American Art before 1900 at the Denver Art Museum:

The department of European and American Art before 1900 oversees a collection that includes more than 3,000 artworks and is composed of painting, sculpture, and works on paper, with significant strengths in early Italian Renaissance, 19th century French painting, and British art from 1400 to 1900.

The Denver Art Museum began acquiring notable examples of European art as early as the 1930s, with donations from Samuel H. Kress, Mr. and Mrs. Simon Guggenheim, and the Havemeyers, to name a few. Their generosity helped initiate a collection that grew in time through gifts and purchases.

Throughout the 1950s, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim donated a significant collection of Old Master paintings, and in 1954, as one of 18 regional museums, the museum was chosen by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation to receive a gift of 33 paintings and four sculptures. Dating from the mid-1300s to mid-1600s, it was the first large collection of Old Masters to be shown in Denver. Additional gifts came from Marion G. Hendrie and the Charles Bayley, Jr. Collections.

KNOWN PROVENANCE

Chiesa di Sant’Agostino, Cremona, Italy. (Galerie Trotti, Paris), 1909. Michele Lazzaroni, Paris, by 1911, until 1926; (Alessandro Contini-Bonacossi, Florence), 1926; purchased 1926 from Contini-Bonacossi by Mr. and Mrs. Simon Guggenheim; gifted in trust 1957 by Mrs. Olga Guggenheim to the Denver Art Museum. Provenance research is on-going at the Denver Art Museum and we will post information as it becomes available.

EXHIBITION HISTORY

“Pinacoteca di Brera, Mostra dedicata ai Tarocchi Visconti Sforza”—Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, 09/23/1999 – 01/15/2000

“Arte Lombarda dai Visconti agli Sforza (Lombard Art from Visconti to Sforza) “—Palazzo Reale, 03/12/2015 – 06/28/2015

If you’ve been following my posts recently, you’ve seen me share quite a few artworks from the Denver Art Museum and many of them were donated to the museum by Mrs. Simon Guggenheim.

If you are interested in knowing how this came to happen, you can find the story in these sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simon_Guggenheim

https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2799

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Simon_Guggenheim_Memorial_Foundation

They don’t come much finer than these two lovely specimen!

Ah, Firenze! I miss you so!

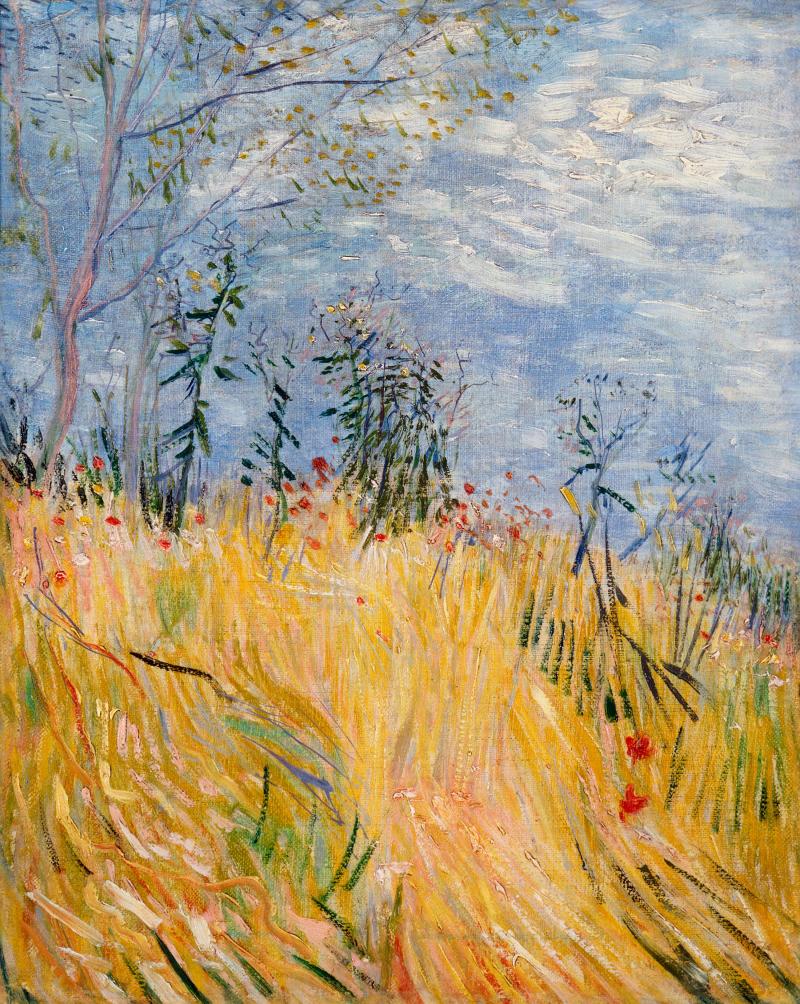

“They are immense stretches of wheat fields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness.”– Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother and sister-in-law shortly before his death.

This article is excerpted from “Vincent van Gogh: The Paris Wheat Field” in Nature as Muse: Inventing Impressionist Landscape.

Vincent van Gogh was born in the Netherlands in 1853 and lived there during his formational years as an artist. He arrived in Paris in spring 1886 at age 33. The self-taught painter had already made several attempts over the past years to systematically study art. Having tried his hand as an art dealer, a teacher, a preacher, a bookseller, a theology student, and a missionary, he had recently left Holland to attend the Antwerp Academy of Art, but had stayed only a few months. Now in Paris, he was determined to dive into the world of art for good. On his brother Theo’s advice, he intended to enter the studio of Fernand Cormon, connect with other painters, become familiar with the art movements of the time, and tap into the flourishing trade in art, because “one must be in the artists’ world.”

Edge of a Wheat Field with Poppies, painted in the summer of 1887, gives a sense of the many influences van Gogh was exposed to during his first year in the “hotbed of ideas” (as he called Paris in a letter to his sister).

The small painting captivates us with its bright contrast between the orange yellow of the field and the complementary radiant blue of the sky, the dark green of the new shoots coming up and the vivid vermillion of the poppies, sprinkled across the canvas in free dashes. The vertical space is evenly divided between earth and sky. The vantage point is surprisingly low to the ground; we look at the scene as though up a hill. This is not the vast expanse of field shown in a Caillebotte painting or van Gogh’s later landscapes, but a detail—a highly fragmented view. A slender poplar arcs along the left edge of the painting, and clusters of budding stalks seem to dance on the horizon line.

With no identifying urban features inside the frame, it is impossible to say whether van Gogh’s wheat field was located in Montmartre, where he was living at the time, or in the vicinity of Paris. While the city of one million inhabitants lay spread out at his feet on one side of the hill of Montmartre, the original rural aspect of the neighborhood was still visible on the other, close by his apartment. Montmartre had been incorporated into the city only a few years earlier, and the far side of the hill was still largely rural in character, complete with vegetable gardens, fields, and windmills, as well as a wide view over the open expanse of the Île de France. This area and the nearby village of Asnières, where he painted views of the Seine and of leisure life, provided van Gogh with many of his rural motifs during his two-year stay in Paris.

The upright format, relatively rare in landscape painting, and the unconventional perspective, which divides the surface of the painting evenly between sky and field, reveal van Gogh’s fascination with Japanese art and its influence on his work in Paris. The colored woodblock prints of artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige had already captured the interest of the Impressionists, strengthening their resolve to free painting from mere representation. Japonisme—enthusiasm for Japanese art and culture—reached its peak in Paris in the 1880s. Ever more dealers stocked woodblock prints, and even department stores sold them at affordable prices; upon his arrival, van Gogh was able to rapidly amass a considerable collection. He exhibited a selection of his prints at the Café Tambourin in March 1887. “The exhibition of Japanese prints that I had at the Tambourin had quite an influence on Anquetin and Bernard,” he later wrote to Theo.

Van Gogh, too, was under the spell, and that year he began to systematically incorporate Japanese motifs into his own work through copies and free interpretations of such prints. In doing so, he replaced the more subdued tonalities of the originals with bright colors intensified through complementary contrasts. Edge of a Wheat Field with Poppies, with its Asian-inspired asymmetrical composition and feather of a poplar tree, may be one of the earliest examples of how van Gogh carried the spatial considerations of Japanese prints into his own work.

While these prints may have been the impetus for the flat, dynamic compositions he created in Paris, van Gogh also looked to Japan as a model for his ideal of a painters colony, where artists could overcome envy and rivalry to work cooperatively. He believed he might find a version of this utopian Japan in the Midi region of southern France. After two years in Paris, van Gogh set out for Arles in spring 1888. He wrote to Theo: “Look, we love Japanese painting, we’ve experienced its influence—all the Impressionists have that in common—and we wouldn’t go to Japan, in other words, to what is the equivalent of Japan, the south? So I believe that the future of the new art still lies in the south after all.”

The ripe field under a cloudy summer sky was to become a dominant motif in van Gogh’s work during his years in the southern towns of Arles and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, and later in Auvers. The small Wheat Field from the environs of Paris is the very first rendering of this motif— an empty field under an open sky, without peasants or livestock. He reinterpreted the idea in a tremendous range of paintings, sounding out the limits of perspective, composition, and color. The field was an open, many-layered metaphor for van Gogh. In a letter to Theo and his wife, Johanna, shortly before his death, Vincent wrote of his pictures: “They’re immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness.”

This attempt to render the emotional inner life of the individual through art—a notion that would not even have occurred to the Impressionists—marks the transition from the positivistic stance of Impressionism to the absolute subjectivity of the Expressionists. A new era had begun.

You must be logged in to post a comment.