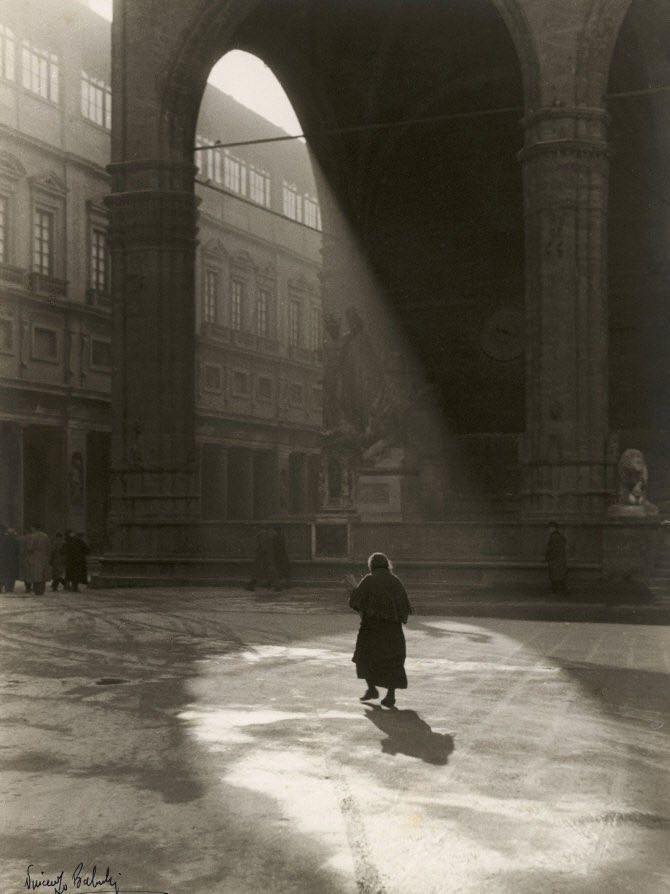

Piazza della Signoria in the 1950s

Piazza della Signoria in the 1950s

Panorama da San Miniato, quanto gli alberi erano ancora bassi e si poteva osservare meglio il panorama. View of Florence from San Miniato, when the trees were still low and you could better see the panorama.

Giardini della Fortezza. Famiglia in posa per una foto ricordo. Anno 1910. Gardens of the Fortezza di Basso, a family posing for a picture in 1910.

Lo struscio sul Ponte Vecchio. Strolling on the Ponte Vecchio.

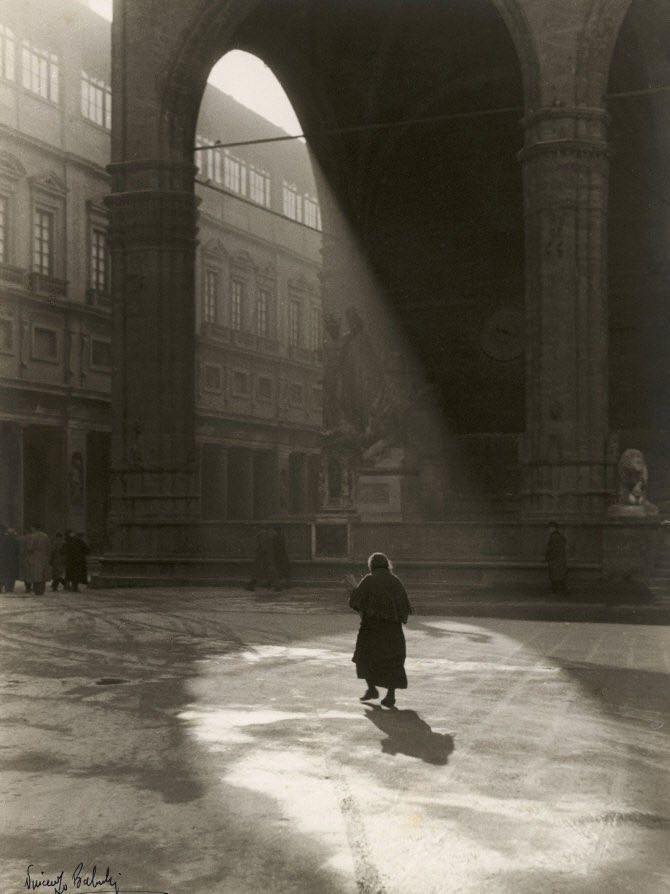

Borgo Ognissanti, negozio Sale e Tabacchi del 1910.

I recently posted an intriguing video about The Mona Lisa. Now, here is a further mystery, utilizing some of the same experts and scholars, the same scientific techniques.

Photographed here is a beautifully-dressed Alice Austen:

Before Diane Arbus and Helen Levitt, there was Austen, one of the earliest female photographers in the country, who produced more than 8,000 images over the course of a long life that began in 1866.

She was, additionally, a landscape designer, a cyclist, an expert tennis player and the first woman on her native Staten Island to own a car. She took her camera everywhere — documenting immigrant communities in New York, street life, lawn tennis matches, her friends, parties, interiors. She often lugged around equipment weighing as much as 50 pounds.

source:

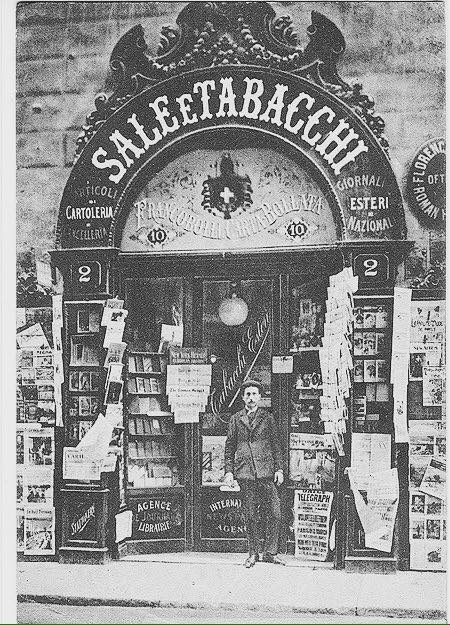

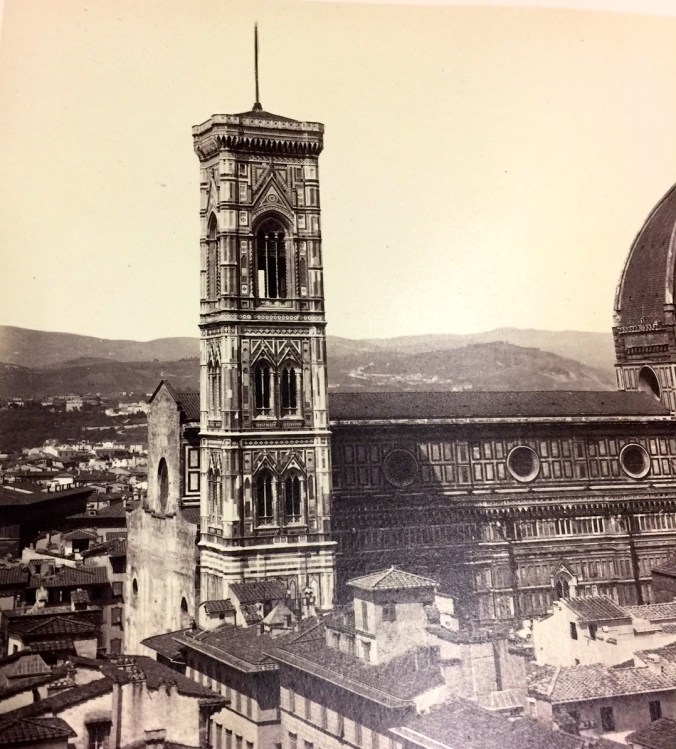

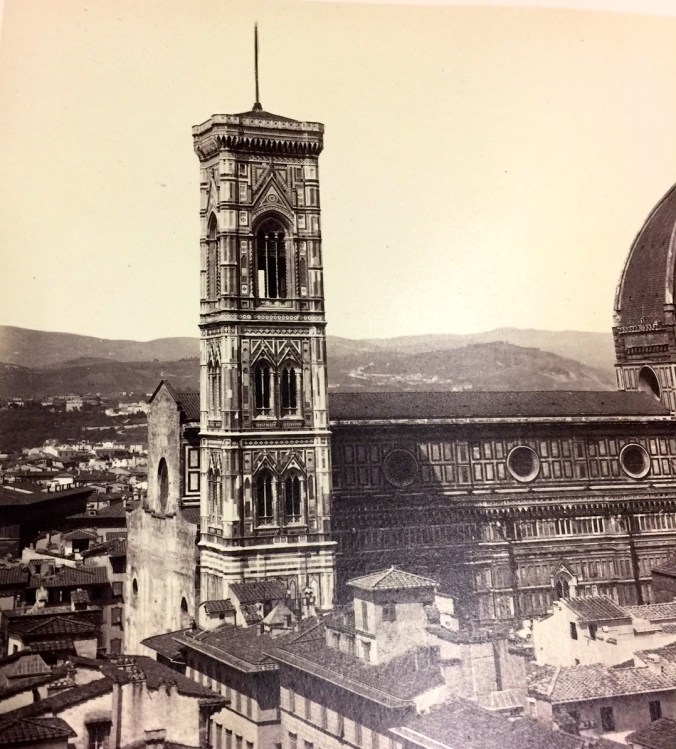

When looking through a photograph album at the Alinari archives, I was shown this photograph of the Duomo in Florence taken sometime before 1874 when the album was created.

When you zero in on the facade of the Duomo, things get very interesting. Instead of the brightly colored and highly embellished facade on the cathedral that one sees nowadays in Florence, this photograph reveals that the facade was left unfinished and unembellished after the Renaissance.

The following photo, of the Duomo today, shows the facade that was added to the building in the 1870s.

If you were a young, aristocratic European man in the late 18th through 19th centuries, you might well have taken a Grand Tour. After finishing your formal education, you would take a kind of gap year (or year and a half), traveling to and through the finest European capitals, including, in Italy, cities such as Venice, Milan, Florence, Rome and Naples.

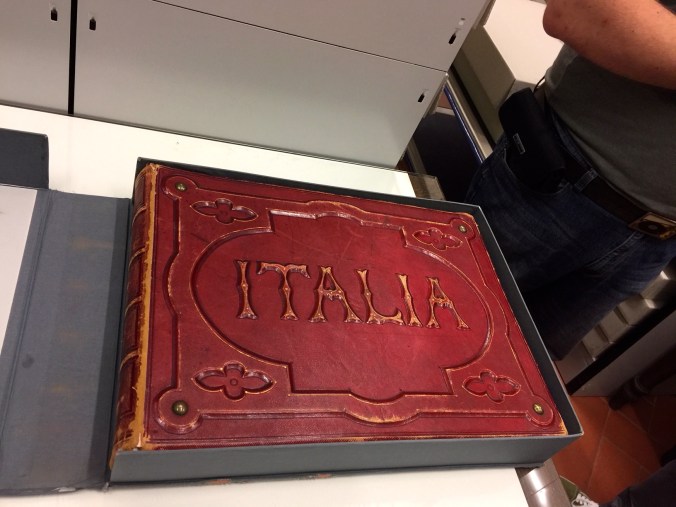

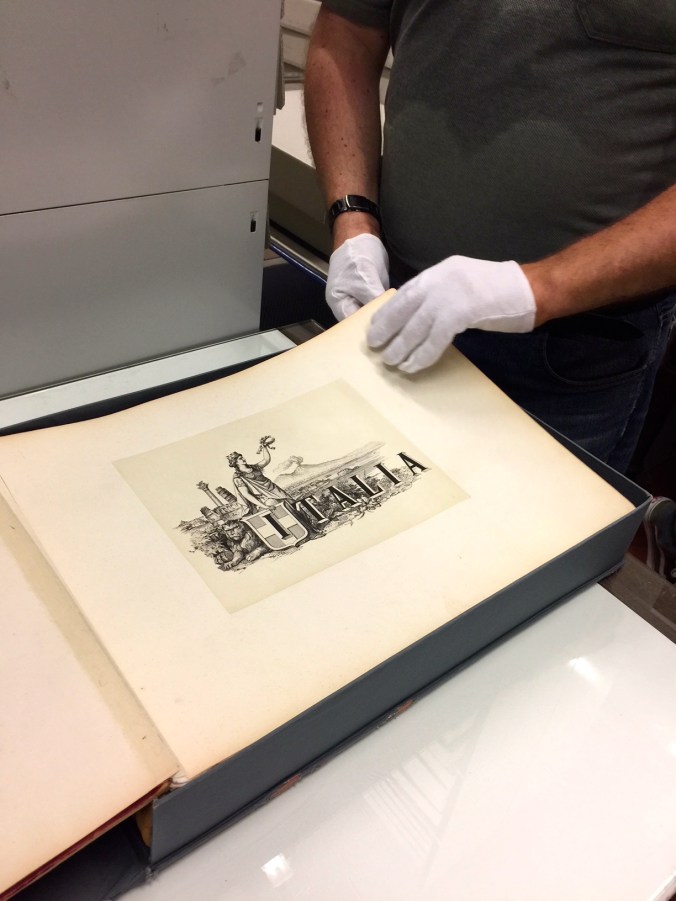

You might have asked Alinari Brothers or another similar firm to create an album for you, comprised of their photographs of your favorite places. The Fratelli Alinari archives in Florence have many of these albums in their archives, and I had the opportunity to look at one of them from 1874.

It begins with a hand-tooled red leather cover. The book measures roughly 20 x 30 inches.

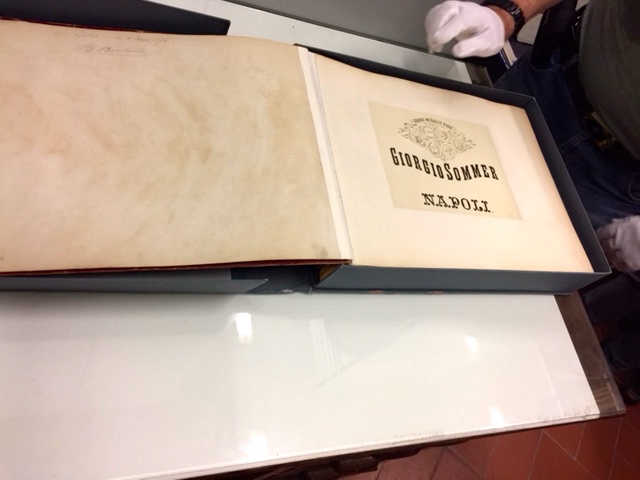

The Frontispiece reveals that this album was created in Naples, by the Giorgio Sommer firm.

This particular album begins with photographs of Torino, Milano, and Venice, as here:

This album then moves to Firenze, and here are 3 images from this section of the book:

Next, the book moves on visually to Rome. Here is a picture of oxen pulling carts through the Roman forum.

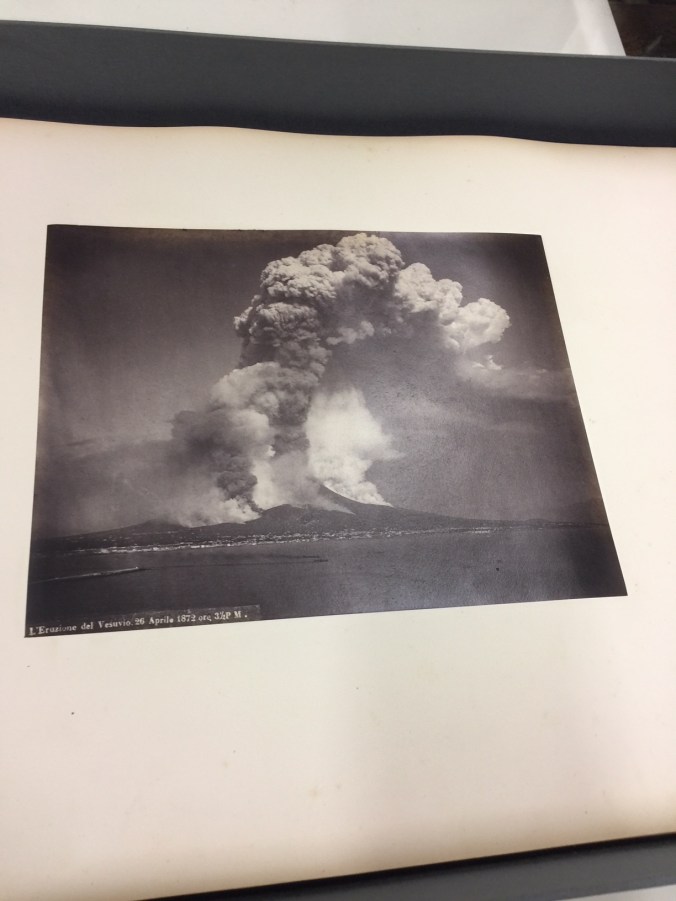

Then it was on to Naples. The following is a picture of Mt. Vesuvius erupting in 1872.

I could (and will) spend hours looking through these albums!

According to my guide at the Alinari archives, an album like this would have cost a young gentleman about $1500 in today’s money.

Today I had an amazing opportunity for art historians: I got to take a guided tour of the Fratelli Alinari headquarters here in Florence.

What a story.

What an archive.

As you can read on the sign above, this photographic business began in Florence in 1852. What you might not know is that this firm was the world’s first of its kind.

When you consider that it was only in 1839 that that Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre developed the first commercially viable photographic process, you understand that these Florentine brothers were astute businessmen, beginning their firm in 1852.

If you want a good source of info, go here: http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=185116

The shop is still in its original location in Florence, not far from the train station.

When you pass into the courtyard, you find the company’s bookshop, where you are offered an array of great posters and books, and also the actual entrance to the Alinari business.

Our guide showed my group some of the earliest cameras ever made and described the methods used to make glass plates.

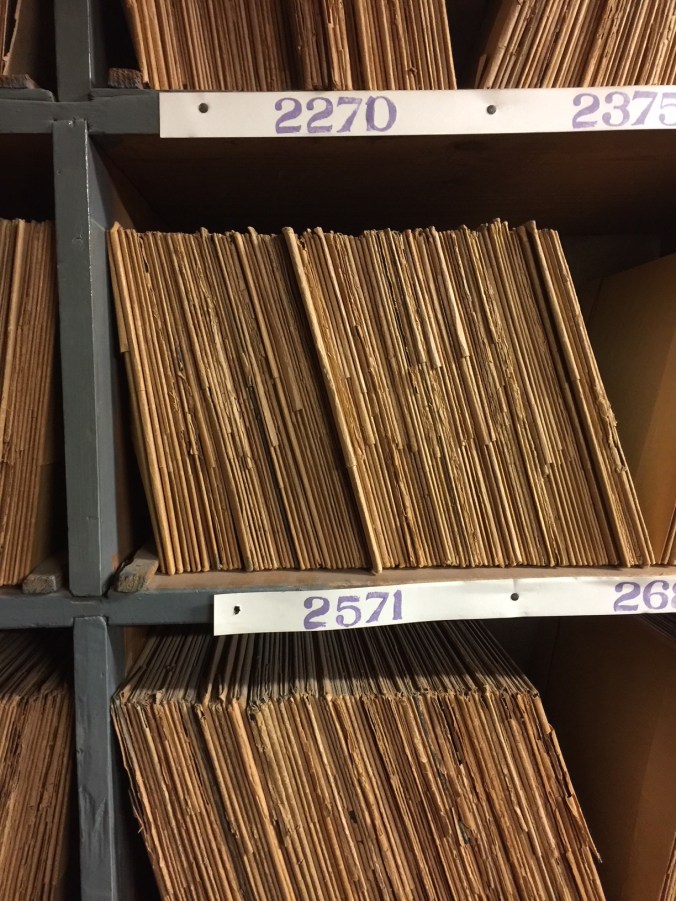

He also showed us some of the rooms where the vast archives are kept, including rooms where the hundreds of thousands of glass plates are stored.

There used to be a museum of the Alinari photographs, but according to Google Maps, it is permanently closed. Fortunately, the online archives are vast.

The Alinari firm was the first to be entrusted with photographing some of the world’s finest collections of art, including the Vatican and the Louvre.

The large object our guide (in green shirt) is showing us was the lens that Alinari built in the 19th century to photograph the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Very impressive.

Today the string of palazzi that line the south side of the Arno River just west of the Ponte Vecchio looks like the picture below. Pay special note to surviving bellower of the church San Jacopo sopr’ Arno in the foreground.

And now here’s a vintage photo of the same area, with a string of older (much) palazzi.

Ponte Vecchio e dietro le case dì Borgo San Iacopo.

In comparing the 2 photographs you can see that the palazzi have been replaced. The entire area was destroyed by German explosives in 1944 as they were being driven out of Florence by the Allied Forces. The newer structures are about 75 years old now.

This church, San Jacopo sopr’ Arno, is very interesting as well:

If you want to learn more about this old church that lies between the Arno and Borgo San Jacopo, here’s a good source: https://wikivisually.com/wiki/San_Jacopo_sopr%27Arno

Palma Bucarelli was born in Rome. She earned a degree in art history at the Sapienza University of Rome.[1]

As a young art historian she worked at the Galleria Borghese and in Naples. During her thirty-three years as head of the Italian National Gallery of Modern Art, Bucarelli was responsible for protecting the gallery’s collections from damage while it was closed during World War II; she arranged to place paintings and sculptures in historic buildings including the Palazzo Farnese and Castel Sant’Angelo.[2] She was one of the Italian delegates to the First International Congress of Art Critics, held in 1948 in Paris.[3]

After the war, she oversaw such events as exhibitions of works by Pablo Picasso (1953), Piet Mondrian (1956), Jackson Pollock (1958), Mark Rothko (1962), and the Gruppo di Via Brunetti (1968). She defended controversial works such as Piero Manzoni‘s ‘”Merda d’Artista” and Alberto Burri‘s “Sacco Grande” (1954).[1] Her strong support for abstract and avant-garde works made international headlines in 1959, when she was accused of a bias against figurative art in a public debate.[4] In 1961 she was in the United States, where she gave a lecture in Sarasota, Florida[5] and attended the opening of a major exhibit on Futurism at the Detroit Institute of Arts.[6]

Palma Bucarelli married her longtime partner, journalist Paolo Monelli, in 1963. She died in Rome in 1998, from pancreatic cancer, aged 88 years. Her personal collection of art was donated to the National Gallery. Her famously elegant wardrobe was donated to the Boncompagni Ludovisi Decorative Art Museum in Rome. A street near the GNAM was renamed in her memory.[2] The Gallery mounted a show about her influence, “Palma Bucarelli: Il museo come avanguardia”, in 2009.[7]

You must be logged in to post a comment.