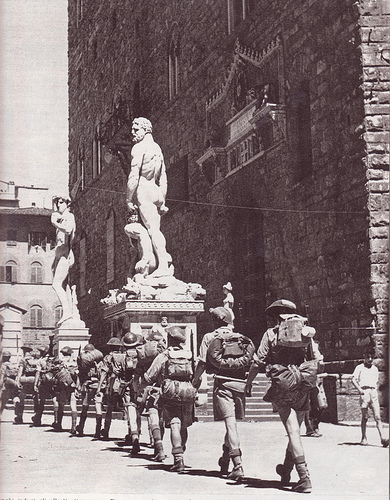

In 1565, by connecting the Uffizi and the Pitti and provided the Medici with an escape route in the event of political unrest. Its narrow hallways are decorated with more than a thousand paintings, mostly self-portraits, by many of the artists whose works adorn the walls of the city’s museums and churches. Farther north is the Palazzo Vecchio (the town hall), the Duomo, and the Accademia, home to the world’s most famous piece of marble, Michelangelo’s David.

In the summer of 1944, war placed this legendary city, and centuries of creative achievements, in danger of utter destruction.

ON NOVEMBER 10, 1943, Adolf Hitler remarked to Ambassador Rudolf Rahn, “Florence is too beautiful a city to destroy. Do what you can to protect it: you have my permission and assistance.” Hitler’s affection for the city initially gave Florentine Superintendent Giovanni Poggi and other city officials hope that Florence would be spared the fate of Naples. The fact that Rome and Siena had escaped major damage also encouraged them.

But, as Allied soldiers inched closer each day, a small group of dedicated souls—now seen as guardian angels of Florence—became increasingly concerned that the coming battle would overtake their city. They had few resources and dwindling options. These benefactors’ best hope was to push Germany and the Allies to jointly declare Florence an “open city,” first suggested by the Director of the Kunsthistorisches Institut, Friedrich Kriegbaum.

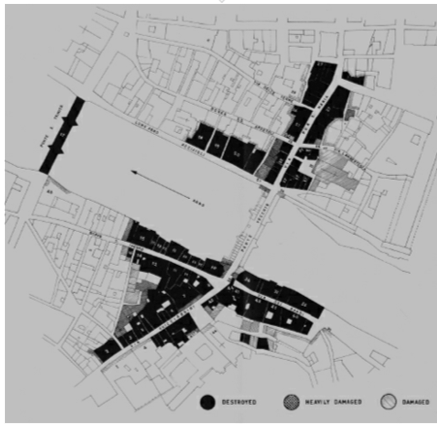

But for a city to be declared “open,” it had to be undefended; there could be no military targets; and both sides had to have freedom of entry. In Florence, German forces had positioned two artillery batteries in the della Gherardesca and dei Semplici Gardens. They had stationed soldiers at numerous mortar positions in the city.

Additionally, Florence, like Rome before it fell to the Allies, served as a major rail transport hub for the German Army. Even after the Allies’ air attacks on the Santa Maria Novella and Campo di Marte marshaling yards, men and materiel moved through the city.

Undaunted by these facts, German leaders referred to Florence as an “open city,” accusing the Allies of refusing to publicly affirm that designation. For their part, the Allies wouldn’t declare Florence an open city until the Germans removed their guns and soldiers.

The standoff held through the spring and early summer of 1944, while Allied forces were engaged in combat operations hundreds of miles to the south. Things grew much more urgent following the liberation of Rome in June and of Siena in July.

City officials believed that their portable art treasures, tucked away by Poggi in Tuscan villas, were safe. But protecting the city’s architectural treasures still depended upon securing an official, unequivocal declaration of Florence as an open city.

Members of the principal group working toward this designation were the German Consul, Gerhard Wolf; the Archbishop of Florence, Cardinal Elia Dalla Costa; the Extraordinary Envoy and Minister Plenipotentiary of San Marino to the Holy See, Marchese Filippo Serlupi Crescenzi; and the Swiss Consul in Florence, Carlo Alessandro Steinhäuslin. These four men did more to save Florence than anyone else.

After four years of service in the German Army, Gerhard Wolf attended Heidelberg University, where he met Rudolf Rahn, who would become a lifelong friend. In the years following graduation, both would enter Germany’s Foreign Service. Seeking to distance himself from the Nazi Party, Wolf accepted a position as the German Consul to Florence.

Cardinal Dalla Costa, a seventy-two-year-old prelate, was another of the city’s guardians. Soft-spoken yet forceful, he assumed an increasingly visible role in defense of the city. During Hitler’s 1938 visit, he ordered that the windows of his palace be shut in symbolic protest. He declined to participate in the official celebrations, explaining that he did not worship “any other cross, if not that of Christ.”

As the situation became more desperate, the cardinal agreed to issue notices that stated, “His Eminence Cardinal Elia Dalla Costa, Archbishop of Florence, declares that this building and the artworks inside, are under the protection of the Holy See.” While he pleaded with the German commanders to respect Florence as an open city, he did so knowing that, “in order to truly protect Florentine works of art, it would be necessary to place a huge pavilion made of impenetrable steel and unbreakable bronze, to cover the entire city.”

Edsel, Robert M.. Saving Italy: The Race to Rescue a Nation’s Treasures from the Nazis, W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.

You must be logged in to post a comment.