How lucky can you get?! I recently joined some Italian language classes but the great news is that the school is housed within a Renaissance palace considered to be a part of the artistic/historic patrimony of fabulous Florence! It fills me with pleasure each time I walk inside that storied building and up its spectacular stone stairway!

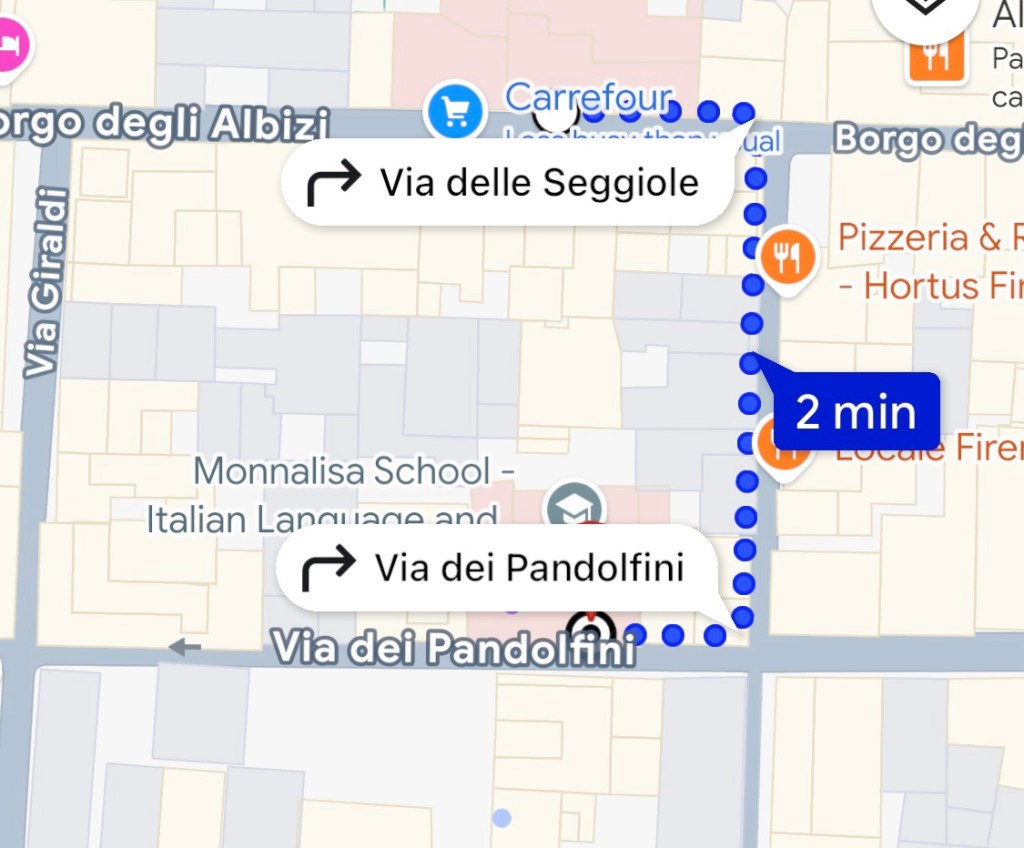

My photos below show the exterior located on via dei Pandolfini.

Now that you’ve seen the outside of the building, let me tell you a little about the interior! I’ll practice my translating skills, if you don’t mind. See each one of my translations after each paragraph in Italiano. The text is from Wikipedia Italia.

Palazzo Galli Tassi è un edificio storico di Firenze, situato in via dei Pandolfini 20, con un affaccio anche su borgo degli Albizi 23. Il palazzo appare nell’elenco redatto nel 1901 dalla Direzione Generale delle Antichità e Belle Arti, quale edificio monumentale da considerare patrimonio artistico nazionale ed è sottoposto a vincolo architettonico dal 1914.

Need a translation? I’m happy to oblige:

Palazzo Galli Tassi is an historic building in Florence at Via del Pandofini 30, with a 2nd entry on Borgo deli Albizi 23. The palace appears in a list published in 1901 by the Director General of Antiquities and the Fine Arts, which includes monumental buildings considered to be part of the artistic patrimony of the country and it has been under the protection of the state since 1914.

Eretto sulle preesistenze di varie case corti mercantili trecentesche, il palazzo viene tradizionalmente fatto risalire agli anni in cui risulta di proprietà di Baccio Valori (dal quale una delle denominazioni tradizionali dell’edificio), nel primo quarto del Cinquecento. Dopo la sua morte (1537) la proprietà, confiscata, passò ai Bellacci, ai Capponi e ai Dazzi, fino a che nel 1623 venne acquistata dai Galli Tassi.

It was erected over pre-existing 13th century houses of merchants; the palace is traditionally dated to the years in which it was owned by Baccio Valori (from which came one of the traditional names of the building), in the first quarter of the 16th century. After his death in 1537 the property was confiscated and passed to Bellacci, then to Capponi and to the Dazzi families, until in 1623 it was acquired by Galli Tassi.

Nel 1630, in previsione delle nozze di Agnolo Galli con Maddalena Carnesecchi (1632) furono intrapresi numerosi lavori di ampliamento e abbellimento degli interni. In particolare Federico Fantozzi riferisce di interventi di ammodernamento condotti nel 1645 da Gherardo Silvani (ma su base documentaria Francesca Parrini riconduce anche questi al cantiere del 1630-1633), al quale si devono tra l’altro le finestre inginocchiate del piano terreno: lo stato dell’edificio determinato da tali lavori è documentato da un cabreo datato al 1753, con la veduta assonometrica del palazzo assieme ad altre proprietà su via delle Seggiole, pubblicato da Gian Luigi Maffei.

In 1630, as part of the nuptials of Agnolo Galli with Maddelena Carnesecchi (1632) numerous renovations and amplifications were performed, further beautifying the interior. Federico Fantozzi in particular noted in his writings about modernizations that were conducted in 1645 by Gherardo Silvani (but on the documentary basis, Franceso Parrini noted in 1630-33), of which were added the kneeling windows of the ground floor: an axiomatic view of the palace was later published by Gian Luigi Maffei.

All’intervento del Silvani sarebbero seguiti i più tardi lavori condotti da Gasparo Maria Paoletti tra il 1762 e il 1763, periodo al quale risale l’imponente scalone neoclassico a due rampe. La situazione negli ultimi anni di proprietà Galli Tassi è attestata da una serie di piante, prospetti e sezioni sempre conservati nell’Archivio di Stato di Firenze e resi noti da Piero Roselli e da Gian Luigi Maffei. Alla morte dell’ultimo membro di questo ramo della casata, il conte Angiolo Galli Tassi (1792-1863, ben noto come benefattore dell’ospedale di Santa Maria Nuova), la proprietà passò per lascito testamentario agli Ospedali della Toscana.

The intervention of Silvani would be followed later works conducted by Gasparo Maria Paoletti between 1762 and 1763, a period in which were realized neoclassic stairways with two ramps. In the last years of the ownership of Galli Tassi a series of plans, perspectives and sections were made and always conserved at the State Archives in Florence; these were noted by Piero Roselli e by Gian Luigi Maffei. At the death of the last member of this branch of the house, count Angiolo Galli Tassi (1792-1863, noted as a benefactor of the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova) the ownership passed by will to the Hospital of Tuscany.

Negli anni di Firenze Capitale (1865-1871) il palazzo e gli edifici confinanti già dei Galli Tassi (in via de’ Pandolfini 18 e borgo degli Albizi 23) furono affittati per essere adibiti a sede del Ministero dell’agricoltura, dell’industria e del commercio: il generale stato di abbandono delle proprietà portò “a molti lavori di risarcimento e di trasformazione” tesi ad aumentare la superficie utile dell’edificio. In particolare, su progetto dell’architetto Paolo Comotto e direzione dei lavori dell’ingegner Francesco Malaspina, il grande salone fu diviso sia in altezza sia in pianta, ricavandone otto stanze, e la terrazza fu chiusa sul fronte di via Pandolfini ricavandone sei stanze. Furono inoltre aperte o chiuse varie finestre e porte e rifatti diversi pavimenti. Con il trasferimento della capitale a Roma il palazzo fu adibito a uffici per la Prefettura e l’Amministrazione Provinciale, fino a che venne acquistato dall’imprenditore napoletano Girolamo Pagliano, noto per essersi fatto promotore della costruzione del teatro attualmente noto come Verdi. Pervenne poi, per via ereditaria, alla famiglia Borgia.

In the years that Florence was the Capitol of the newly united Italy (1865-1871) the palace and the buildings already known as Galli Tassi (with the 2 same addresses as today) were used as the seat of the Minister of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce; the general state made many changes to the property. In particular, architect Paolo Comotto, directed by the engineer Franscesco Malaspina, the grand salon was divided in height to create 8 rooms and the terrace was closed on the front of Via Pandolfini to make 6 rooms. There were various windows and doors which received different flooring levels. With the transfer of the Capitol to Rome, the palace was turned into an office for the Prefecture and Province Administration, until it was acquired by the Neapolitan businessman Girolamo Pagliano, noted for being made the promoter for the construction of the theater now known as the Verdi. It then went by will to the Borgia family.

Al 1925-26 si datano importanti interventi di restauro, compreso quello condotto da Amedeo Benini sui graffiti della facciata. Importanti lavori di modifica interna e di restauro sono stati eseguiti tra il 1990 e il 1994, ma un altro cantiere doveva aver già interessato la fabbrica negli anni settanta, visto che il repertorio di Bargellini e Guarnieri la dice “recentemente restaurata”.

From 1925-26 important restorations took place conducted by Amedeo Benini with the sfraggiti on the facade. Between 1990 and 1994 important modifications and restorations were executed, but there must have already been a renovation in the 1970s seeing that Bargellini and Guarnieri reported that the building had been “recently restored.”

La facciata si presenta organizzata su quattro piani e sette assi, con grandi finestre ad arco incorniciate da conci in pietra, chiusa in alto da una altana, come detto ora tamponata e finestrata, nell’insieme del tutto rispondente a quanto documentato dal cabreo del 1753. Sotto il secondo ricorso è lo stemma aquilino dei Valori (di nero, all’aquila al volo abbassato d’argento, seminata di crescente del campo). Per quanto riguarda i graffiti, che caratterizzano l’edificio sia con un disegno a pietre squadrate sia con fasce decorate dove ricorrono iscrizioni e, insistentemente, il tema della vela gonfia di vento attributo della Fortuna, si è ipotizzato (Eleonora Pecchioli), nonostante i molti rimaneggiamenti, che questi possano risalire nella loro formulazione originaria alla fine del Quattrocento o ai primi del Cinquecento, il che porterebbe ad anticipare la datazione della fabbrica rispetto a quanto ipotizzato da tutta la letteratura precedente.

The present facade is organized into 4 floors and seven axes, with large arched windows framed with stone ashlars, closed at the top by a covered terrace completely corresponding to the records of 1753. Under the second stringcourse is the coat of arms of the Valori family black, with an eagle flying low in silver, on a crescent background. Re: the sgraffito, its attributed to Fortuna, with the theme of the sail with wind blowing and according to one hypothesis of Eleonora Pecchioli, the sgraffito could date back to the end of the 15th or early 16th century, although that means it would have been touched up later.

Nell’interno è da segnalare il bel cortile cinquecentesco con un gruppo marmoreo di Ercole e Iole di Domenico Pieratti (commissionato da Agnolo Galli nel 1629 e terminato nel 1659). All’interno sono presenti tra piano terra e piano nobile gli affreschi di Fabrizio Boschi (Ratto di Cefalo al piano terra, 1631), Giovanni da San Giovanni (Amore e Psiche e due gruppi di Putti, piano nobile, 1630-1631), Ottavio Vannini (Selene e Endimione, piano nobile, 1632), Cosimo Ulivelli (Ritratti dei committenti e di un servitore in finte porte del salone al piano nobile, 1640, già attribuito anche al Volterrano) e le Storie del Pastor fido e gli elementi decorativi di Baccio del Bianco e opere di Francesco Furini e Matteo Rosselli.

In the interior is a beautiful 15th century courtyard with a marble sculpture of Hercules and Iola by Domenico Pieratti (commissioned by Agnolo Galle in 1629 and finished in 1659). Frescoes by Fabrizio Boschi decorate the walls from the ground floor to the first floor (The Rape of Cefalus on the ground floor date 1631). Other frescoes by Giovanni da San Giovanni (Cupid and Psyche and 2 groups of putti, first floor, 1630-31); Ottavio Vannini (Selene and Endymion, first floor, 1632); Cosimo Ulivelli (Portrait of the patrons and one of a servant in false doors of the salon on the first floor, 1640, now attributed to Volterrano) and the Storiy of the faithful Pastor and the decorative elements by Baccio del Bianco and works of Francesco Furini and Mattero Rosselli.

Lo scalone. Il palazzo ha inoltre un affaccio su Borgo degli Albizi 23. Questa porzione sorge nel luogo di due case corte mercantili medioevali, unificate nelle forme attuali nei primi decenni del Cinquecento. Sicuramente nella prima metà del Settecento era stato unito alle proprietà dei Galli Tassi, come documenta un cabreo del 1753 pubblicato da Gian Luigi Maffei. Sviluppato su sei assi, il palazzo su questo lato presenta i consueti caratteri propri dell’architettura fiorentina del primo Cinquecento, con finestre e portali incorniciati da bugne di pietra. Al centro della facciata, sotto il secondo ricorso, è uno scudo con l’arme della famiglia Valori (di nero, all’aquila dal volo abbassato d’argento, seminata di crescenti del campo).

The stairway. The building has a second entrance on Borgo degli Albizi 23. This portion was built over two medieval mercantile housess, unified in the forms in the first decades of the 16th century. In the first half of the 18th century the 2 parts were united by the proprietor, Galli Tassi, as documents in the 1853 publication by Gian Luigi Maffei reports. Developed on 6 axes, the building on this side presents the typical Florentine architectural elements of the early 16th century, with windows and doors surrounded by stone ashlars. At the center of the facade, under the second stringcourse is the coat of arms of the Valori family (repeat of above paragraph).

Below are my pictures of the 2nd entrance to the Palazzo, located at Borgo degli Albizi 23.

The maps below show the location of the palazzo, with a blue x marking the spot of the 2nd entrance.

Very soon I will be posting again, showing the interior of the august building.

You must be logged in to post a comment.