I made a beeline for this museum once I had settled into Munich. Wow oh wow, it did not disappoint!

Above, the south facade of the museum.

Before I post on the collection and what caught my eye and imagination, I want to give a little context about this great Bavarian museum. Wikipedia to the rescue as always.

And thanks to Google, you can take a wonderful virtual tour of the museum from your own home. https://artsandculture.google.com/u/0/partner/alte-pinakothek?hl=en

The Alte Pinakothek is an art museum located in the Kunstareal area in Munich It is one of the oldest galleries in the world and houses a significant collection of Old Master paintings. The name Alte (Old) Pinakothek refers to the time period covered by the collection—from the 14th to the 18th century. The Neue Pinakothek, re-built in 1981, covers 19th-century art, and Pinakothek der Moderne, opened in 2002, exhibits modern art. All three galleries are part of the Bavarian State Painting Collections, an organization of the Free state of Bavaria.

King Ludwig I of Bavaria ordered Leo von Klenze to erect a new building for the gallery for the Wittelsbach collection in 1826. When built, the Alte Pinakothek was the largest museum in the world and structurally and conceptually advanced through the convenient accommodation of skylights for the galleries. Even the Neo-Renaissance exterior of the Pinakothek clearly stands out from the castle-like museum type common in the early 19th century. It is closely associated with the function and structure of the building as a museum. Very modern in its day, the building became exemplary for museum buildings in Germany and in Europe after its inauguration in 1836, and thus became a model for new galleries like the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, and galleries in Rome, Brussels and Kassel.

The museum building was severely damaged by bombing in World War II but was reconstructed and reopened to the public on 7 June 1957. Director Ernst Buckner oversaw the rebuilding project, ensuring that the building remained true to its original architecture. The ornate, pre-war interior, including the large loggia facing the south façade in the upper floor, was not restored.

A new wall covering system was created in 2008 for the rooms on the upper floor of the museum with a woven and dyed silk from Lyon. The new color scheme of green and red draws on the design of the rooms dating back to the time of construction of the museum, and was predominant until the 20th century. Already for King Ludwig I and his architect Leo von Klenze, the use of a wall covering alternately in red and green represented the continuation of a tradition that dates back to the exhibition of the old masters of the late 16th century in many of the major art galleries of Europe (Florence, London, Madrid, St. Petersburg, Paris, Vienna).

The Wittelsbach collection was begun by Duke Wilhelm IV (1508–1550) who ordered important contemporary painters to create several history paintings, including The Battle of Alexander at Issus of Albrecht Altdorfer. Elector Maximilian I (1597–1651) commissioned in 1616 four hunt paintings from Peter Paul Rubens and acquired many other paintings, especially the work of Albrecht Dürer. He even obtained The Four Apostles in the year 1627 due to pressure on the Nuremberg city fathers. A few years later however 21 paintings were confiscated and moved to Sweden during the occupation of Munich in the Thirty Years war. Maximilian’s grandson Maximilian II Emanuel (1679–1726) purchased a large number of Dutch and Flemish paintings when he was Governor of the Spanish Netherlands. He bought, for example, in 1698 from Gisbert van Colen 12 pictures of Peter Paul Rubens and 13 of Van Dyck, with the pictures of Rubens from the personal estate of the artist which the artist had never intended for to be sold.

The Elector’s cousin, Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine (1690–1716), collected Netherlandish paintings. He ordered from Peter Paul Rubens The Big Last Judgment and received Raphael’s Canigiani Holy Family as a dowry of his wife. Charles Theodore, Elector of Bavaria (1742–1799) had a strong preference for Netherlandish paintings as well, among other paintings he acquired Rembrandt’s The Holy Family. By the late 18th century, a large number of the paintings were displayed in Schleissheim Palace, and accessible to the public.

After the reunion of Bavaria and the Electorate of the Palatinate in 1777, the galleries of Mannheim, Düsseldorf and Zweibrücken were moved to Munich, in part to protect the collections during the wars which followed the French revolution. At least 72 paintings including The Battle of Alexander at Issus were taken to Paris in 1800 by the invading armies of Napoleon I; Napoleon was a noted admirer of Alexander the Great. The Louvre held it until 1804, when Napoleon declared himself Emperor of France and took it for his own use. When the Prussians captured the Château de Saint-Cloud in 1814 as part of the War of the Sixth Coalition, they supposedly found the painting hanging in Napoleon’s bathroom.Most of the paintings have not been returned.

With the secularisation many paintings from churches and former monasteries entered into state hands. King Ludwig I of Bavaria collected especially Early German and Early Dutch paintings but also masterpieces of the Italian renaissance. In 1827 he acquired the collection Boisserée with 216 Old German and Old Dutch masters; in 1828, the king managed to also purchase the collection of the Prince Wallerstein, with 219 Upper German and Upper Swabian paintings. In 1838 Johann Georg von Dillis issued the first catalogue.

Durer’s Self-Portrait

After the times of King Ludwig I the acquisitions almost ended. Only from 1875 the directors Franz von Reber and Hugo von Tschudi secured important new acquisitions, such as the Madonna of the Carnation of Leonardo da Vinci and The Disrobing of Christ of El Greco.

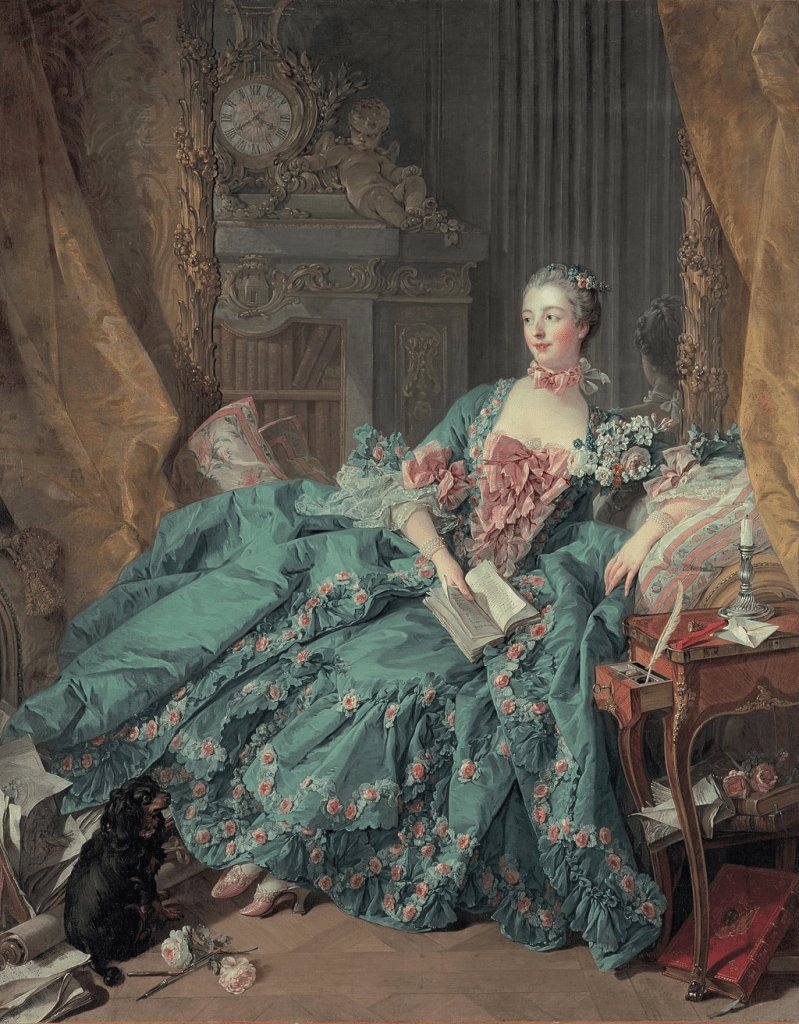

The predilection of the Wittelsbach rulers for some painters made the collection quite strong in those areas but neglected others. Since the 1960s the Pinakothek has filled some of these gaps: for example, a deficit of 18th-century paintings was addressed by the integration into the collection of works loaned from two Bavarian banks. Among these paintings were Nicolas Lancret’s The Bird Cage and François Boucher’s Madame Pompadour.

In April 1988, the serial vandal Hans-Joachim Bohlmann splashed acid on three paintings by Albrecht Dürer, namely Lamentation for Christ, Paumgartner Altar and Mater Dolarosa inflicting damage estimated at 35 million euros. In 1990 Dierick Bouts’ Ecce agnus dei was acquired.

On 5 August 2014, the museum rejected a request by a descendant of the banker Carl Hagen for the repatriation of Jacob Ochtervelt’s Das Zitronenscheibchen (The Lemon Slice) on the grounds that it had been unlawfully acquired as a result of Nazi persecution. An investigation by the museum established that it had been lawfully purchased at the time for a fair price and that the Hagen family’s interest extended only to a security on the painting.

The museum is under the supervision of the Bavarian State Painting Collections which also owns an expanded collection of several thousand European paintings from the 13th to 18th centuries. Especially its collection of Early Italian, Old German, Old Dutch and Flemish paintings is one of the most important in the world.

More than 800 of these paintings are exhibited at the Old Pinakothek. Due to limited space in the building, some associated galleries throughout Bavaria such as the baroque galleries in Schleissheim Palace and Neuburg Palace additionally have works by the Old Masters on display.

German paintings 14th–17th century:

The Alte Pinakothek comes with the most comprehensive collection of German Old Masters worldwide

Early Netherlandish paintings 15th–16th century:

One of the most impressive collections worldwide especially for Early Netherlandish paintings

Dutch paintings 17th–18th century:

Due to the passion of the Wittelsbach rulers this section contains numerous exquisite paintings.

Flemish paintings 16th–18th century:

The collection contains masterpieces of these painters

Italian paintings 13th–18th century:

The Italian Gothic paintings are the oldest of the gallery and then all Schools of Italian Renaissance and Baroque Painting are represented

French paintings 16th–18th century:

In spite of the close relationship of the Wittelsbachs to France it is the second smallest section of the collections

Spanish paintings, 16th–18th century:

Though this is the smallest section, all major masters are represented

You must be logged in to post a comment.