Florence (Firenze)

Here he is, in all his Il Duomo splendor!

Ghiberti’s “Gates of Heaven” currently look like doors to a bank!

The Florence Baptistery is currently enveloped in a gray shrouding of some sort. This friendly detective, at your service, is on the case and will update you when information becomes available.

Seriously, are they cleaning it under the shroud or is the monument wrapped up to keep it warm for the winter?

I’ll get back to you on that!

UPDATE: According to my local anonymous sources: the shroud covers the scaffolding which was erected so the monument can be cleaned and shined up to match the shining Duomo, since they are more or less a matched set.

In the meantime, this is how the doors that Michelangelo called “the gates of paradise” look today. You can’t tell if these tourists are lining up to look at the art or queing up to draw money from the ATM. Oh, wait a minute, no one ques in Italy, so it must be the art!

Do you see what I see?

Nov. 4, 1966 Florence flood

Here’s how the Ponte Vecchio looks today:

And here is how it looked 48 years ago today:

Here’s a detail showing how the flood waters were not the only aspect of the disaster, but the debris including downed trees also hit the famous bridge.

Santa Maria Novella piazza under high waters:

Flood waters moved and destroyed thousands of cars.

You can read more about the flood here:

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/dec/26/vasari-last-supper-reassembled

You can see footage here:

Recipe for magic…

Mix one part Pucci and one part antique landmark and what do you get? A moment of magic.

Step 1. Take a famous old Italian monument (Medieval is the best flavor if you can get it. It is hard to come by, so just do the best you can):

For the purpose of our post today, we will start with the Baptistery in Florence. It is the striped building in the front of this 3 part complex, which includes the Cathedral (il duomo), the campanile (belltower), and the octagonal Baptistery.

Step 2. Add a colorful vintage design from a later master, say something from the 20th century. The Marquise Emilio Pucci will do nicely for our demonstration.

We’ll use this Pucci scarf today, which was created in 1957 with the Florence Baptistery as its central motif. Pucci created a series of silk scarves using the most famous world cities as inspiration. He was a Florentine, so it is quite interesting that, of all the structures in his native city, he chose the Baptistery above all others as his iconic symbol of his town.

Step 3. Put the ingredients into a large vessel of some sort, kind of like a giant cocktail shaker, while wearing a pair of vintage Pucci capri pants and a top fashioned from the same silk as the scarf you are shaking up, as seen above.

This next step is important to the success of your final product: Be sure to notice your background while you are mixing things up. You see one of your ancestors standing in front of the Baptistry and holding the scarf. This will get you in the right frame of mind to enjoy your dressed up monument.

Step 4. Shake, shake, shake. And eccola!

Step 5. Enjoy! You’ve got yourself a dressed up monument! A new masterpiece! You have breathed new life into an old item. Think of it as re-purposing on a grand scale. What was old is new again. You can see something old with new eyes. Whatever saying floats your boat.

Step 6. Stand back and look at your newly finished monument.

Be brave, because change can be hard…you can bet that not everybody will embrace it…

Step 7. Move all around your monument to see it from every imaginable angle…

And in every kind of weather condition…

You want to see it on sunny days…

See how it shines!

And on cloudy days:

And even in the rain:

Step 8. Look, look, look. Looking can be hard work, but not when you have something this fun to gaze at. Look at your masterpiece at night:

And try to catch it with the moon in the sky…

Step 9. Then, look at it again in the sunshine, because…

Now you see it…

And now you don’t.

Poof! The cover is gone and you are back to your old monument. But, now you will have a better appreciation for it.

Ha ha. If you’re wondering what is up with all of this, it is very simple to explain.

Last June 17-20, for only 3 days, the iconic Baptistery in Florence was decorated with a reproduction of Pucci’s Battistero scarf, designed in 1957. Pucci’s scarf interprets an aerial view of Battistero San Giovanni in the brilliant hues of a Mediterranean landscape, using vibrant lemon yellow, orange, fuchsia and the emblematic Emilio pink. Never before had the Baptistery been so artistically reinterpreted, as it was for three days last June, in canvas printed with a Pucci design.

The Apse side of the Baptistery was clad in a scale reproduction of the original Battistero scarf design as a whole, having been reproduced and framed in large scale in its entirety.

The other seven sides of the octagonal building were covered in almost 2.000 square-meters of canvas, printed in a to-scale rendering of the famous Pucci design. Faithfully following the contours of the building, it was completely enveloped in rich and loud splashes of Pucci line and color.

The City of Florence was delighted to drape its iconic monument with a design by the famous Italian fashion House of Emilio Pucci, for the city has been celebrating this year the 60th anniversary of the Center of Florence for Italian Fashion. Several fashion labels, including Gucci, Ferragamo, and Cavalli also participated in the festival to help celebrate their Florentine heritage as a part of the Firenze Hometown of Fashion initiative. Palazzo Pucci opened its archives during the celebration as well and fifty photos from editorials shot by Vogue Italia were also on display in the city.

Pucci’s gigantic scarf building covering was conceived by Pitti Imagine, the branch of the Center of Florence for Italian Fashion that creates fashion events.

Fans could follow the unveiling of the Baptistery’s new look using the hashtag #MonumentalPucci on social networks. While the display was being put up, Pucci posted teasers of the finished product. This tag was also used to share archival images of the house’s fashions over the years.

The Baptistery is currently being restored and Pucci, which is part of the LVMH (Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton) group, will substantially contribute financially to the restoration on the octagonal monument, in the same way that other design-related companies are supporting to the care and upkeep of the many of Italy’s monuments.

A detail of the scarf designed by Emilio Pucci in 1957

This temporary new landmark of the Baptistery wrapped in a Pucci design captured the attention of every tourist, who were seen gawking at and taking selfies in front of the monument. The whole atmosphere was a bit surreal. Lucky were all those who managed to see Florence with its Baptistery “dressed” in Pucci—such moments go down in the history of fashion and stay there forever.

Even if you weren’t one of the lucky ones who saw the dressed up monument in the flesh, you can experience a sense of it in these cool videos.

7.5 minutes of Italian high fashion from 1952

Enter 1952 if you dare:

There are some shots of Giovanni Battista Giorgini, who started it all in Florence, for those with eagle eyes.

Ciao a tutti!

How Italian high fashion found its groove. Part 1.

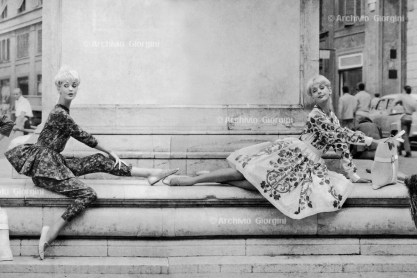

Ask any fairly sophisticated person you know where the two following photographs were taken, and chances are very good…

that the viewer will know instantaneously that the pictures were taken in Italy. Certo!

And that same person will also no doubt know that in Italy presenting una bella figura is one of the most important aspects of daily life. Italians, male and female, are well known for their sense of style and its major component, fashion. Italy is rightly recognized as a hub of fashion, with many eminent names such as Armani, Dolce & Gabbana, Donatella Versace, Missoni, Prada, Cavalli, Valentino, Taccini, Gucci, Garavanni and Moschino and many more in the mix. These designers are in great local and international demand. But it hasn’t always been this way.

So, how did this situation evolve?

It would seem that one man had a vision to form a world of high Italian fashion to compete with the French haute couture. This new Italian high fashion incentive, first formed in the mind of Giovanni Battista Giorgini, rose like a phoenix out of the ashes of WWII and came to forefront of the world stage.

Florentine count, Giovanni Battista Giorgini (1898-1971), was perfectly poised to bring his vision to fruition, for he knew the American market very well, having been involved in exporting Italian fashion goods to North America since 1923. He had been involved in promoting Italian craftsmanship–specifically the “Made in Italy” initiative– in the United States until the 1929 Stock Market Crash and the dastardly political developments in Fascist Italy brought his efforts to a close.

Photo above from Archivio Giorgini in Florence.

Giorgini’s ambitions for Italian fashion were set aside while the world was caught up in chaos and he served in the armed forces of his country during the lead-up to WWII. During the conflict, Giorgini was in the army, in command of a brigade near Bagni di Vinadio in Piedmont.

By the time the last Allies efforts were underway to take Florence from the Germans, Giorgini and his wife and three sons were living in the Oltrarno neighborhood of the city. It was through that neighborhood that the first column of the Allied army approached Florence. The entire Giorgini family were fluent in English and Giorgini offered to make his home the Allies’ headquarters. The Allies command gratefully accepted.

In 1944, Giorgini was appointed director of the Allied Force Gift Shop, a store for the Allied Force troops. Under his management this successful operation was repeated in other Italian cities. When the War ended, Giorgini was able to return to the United States in an effort to reignite his exporting business, which had been on hold for almost twenty years.

Within a few years, Giorgini was supplying the largest American and Canadian importers and distributors with the finest of Italian products. Among his clients were well-known retailers including I. Magnin; B. Altman; Bergdorf Goodman; H. Morgan; Tiffany; Bonwit Teller and others. To these leading department stores Giorgini exported the best Italian products such as home and fashion accessories including knitted and woven textiles, leather, shoes, as well as ceramics and glass.

Giorgini was uniquely qualified in his role as a successful entrepreneur, although he always preferred the artistic end of the enterprise, not the business end. He was not always comfortable in his role as promoter of Italy to North American businesses, for he was first and foremost a passionate collector of art and antiques, as well as being himself a designer.

Despite his reluctance to operate as a businessman, he always was one step ahead of avant-garde trends. His uncanny ability allowed him to guide Italian manufacturers in modifying their products so that they could meet the ever changing new demands from the marketplace.

It was Giorgini’s brilliance that allowed him to intuit that the incredible artisan craftsmanship for which Italy was known could be brought to bear on the damaged fashion world in post war Italy. He knew that craftsmanship was vital, but was not, alone, enough on which to base the fashion renaissance he foresaw.

He rightly believed that it would take two things to launch the dream he had:

#1 the enhanced production of the high quality textiles for which Florence has always been famous

and

#2 brand new ideas from highly talented designers. Giorgini wanted to stimulate the best and brightest in Italy to create and export an entirely new field of high Italian fashion to the world. And indeed he did bring it about.

Prior to this time, Italian fashion and textile businesses were simply copying their French counterparts, but not adding anything beyond fine craftsmanship to the mix. That wasn’t good enough for Giorgini: he foresaw a world in which Italy not only held its own with its French colleagues, but Italy surpassed them. He set about making this new world happen.

Giorgini’s out-going personality coupled with his aristocratic heritage and his inherent good taste, made him ideal for his role in public relations. He knew how to capitalize on his background and interests, as well as how to enhance his orbit of acquaintances.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, one by one, Giorgini made contact with the leading Italian producers of textiles and clothing, and convinced them to cooperate with his idea. He did the same thing with American buyers and journalists.

Giorgini would often tempt these movers and shakers in the burgeoning field of international fashion by inviting them to share in elegant evenings in his lovely home on Florence’s Via dei Serragli. His beautiful house, furnished with art and antiques, created an environment of elegance and opulence that charmed his foreign guests. There he entertained them with extravagant dinners with concerts and/or dances. It was very hard for anyone to resist. Why would anyone want to?!

Once he had some of the fundamentals in place, Giorgini issued a carefully planned and strategic invitation to European nobility to a big event, a full day of a runway show, held on February 12, 1951 in the ballroom of his beautiful home at #144, Via dei Serragli. One might even be tempted to say that Giorgini had learned some strategies from the U.S. military, so carefully was his initiative planned!

Here’s a photo of the invitation Giorgini and his wife extended

Giorgini’s deep knowledge of the North American markets led him to set his sights on bringing the buyers for American department stores to Florence to show them a series of Italian collections for Spring/Summer 1951. He planned his event so that the American buyers could just pop down to Italy to see what was happening there, right after they had been to Paris catwalk shows. After all, he reasoned, they were already in Europe so perche no? Giovanni Giorgini was a brilliant strategist!

He gave each of his invited guests this challenge: the ladies were kindly requested to wear dresses of pure Italian inspiration. The reason for this unusual request, he further explained, was to present pure Italian fashion as something special to behold.

The first “Italian high fashion show” featured Carosa, Fabiani, Simonetta, the Fontana sisters, Schuberth, Vanna, Noberasco, Marucelli and Veneziani.

In the meantime, the Florentine marquise, Emilio Pucci, had himself already obtained a photo shoot for one of the leading American fashion magazines, Harper’s Bazaar and he invited buyers to see his own collection at Palazzo Pucci. The accessories shown with Pucci’s garments were created by Fratti, Canesi, Proyetti, Gallia & Peter from Milan, the baroness Reutern, Romagnoli, Canessa from Rome and Biancalani from Florence.

Of course Giorgini did not forget to invite the press to his event. Bettina Ballard, then a fashion editor at Vogue, wrote Giorgini a triumphant letter after the event, saying: “Everybody seems interested in Italian fashion, alongside Vogue. I am sure we will be doing something together in the short term.”

Once again, I thank the gods of fortuna for the internet and Youtube. Check out this footage of one of Giorgini’s 1951 fashion shows:

The event at Via dei Serragli was a huge success. Models wore dresses on a single catwalk from the most important Italian designers of the period. Each model carried a number in her hand so that the buyers from I. Magnin, Bergdorf Goodman, B. Altman and other high-end American department stores could identify the maker.

Savvy Giorgini had also invited journalists to his event, including the correspondent for Women’s Wear Daily. Even though the buyers and journalists had just been at the Paris catwalk shows, Italian fashion scored a big win that winter evening in 1951.

American buyers had to wire their firms in the States for increased budgets to purchase from the Italian ateliers; the ateliers themselves were slammed with so many orders that it was almost unbelievable. The American buyers were over the moon with excitement over their new discovery of a previously untapped fashion resource, but were also keen on the price factor. Italian designs at this time were about a third the cost of their Paris equivalents.

It is further said that both Emilio Pucci and Schuberth began their careers that night.

Making the most of the wind under their sales by the fabulous and successful coming-out party at Giorgini’s home, a second fashion event was held the following year at the Grand Hotel in Florence.

These fashion extravaganzas proved to be such a success that Florentine leaders joined the bandwagon and sought a more suitable setting. They enhanced the exhibition of Italian fashion design by hosting it in the Sala Bianca, or the chandeliered and opulently decorated white room, at the famed Palazzo Pitti.

From this beginning in February of 1951, created by Giorgini, new talents were spawned, including Capucci, Galitzine, Krizia, Valentino and Mila Schon.

Giorgini continued to work with these shows and each year he increased their excitement by launching new initiatives, such as one year it was all about “textile promotion”.

Giorgini was also the first person to fully understand the potential of the new importance of prêt à porter, or ready-to-wear, and the so-called boutique lines. One could almost call the count a democrat. He was all over making high fashion available to regular people.

It’s a fact: Giovanni Battista Giorgini launched the world of Italian high fashion design! I am sure I speak for aficionado’s everywhere when I exclaim one big grazie a Giorgini!

This story isn’t finished, however, and I’ll be back with a second post presto. Stay tuned!

Updated: Nov. 12, 2014 I would like to thank the Director of the Archivio Giorgini in Florence, Mr. Neri Fadigati, for reading this post and making suggestions for improving it.

But in the meantime, here is a vintage video from 1959, which shows Giorgini speaking about Italian fashion at about 4 minutes in.

You must be logged in to post a comment.