Lovely Padova, or Padua, is a city and comune in Veneto, northern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Padua and the economic and communications hub of the area. Padua’s population is 214,000 and when the city is included, with Venice (Venezia) and Treviso, in the Padua-Treviso-Venice Metropolitan Area (PATREVE), the sum population of around 2.5 million.

Padua stands on the Bacchiglione River, 25 miles west of Venice. The Brenta River, which once ran through the city, still touches the northern districts.

Its agricultural setting is the Venetian Plain (Pianura Veneta). To the city’s south west lies the Euganaean Hills, praised from time immemorial by Lucan and Martial and later by Petrarch, Ugo Foscolo, and Shelley.

Padua was the setting for most of the action in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew and in and in Much Ado About Nothing, Benedick is named as “Signior Benedick of Padua.” There is a play by the Irish writer Oscar Wilde entitled The Duchess of Padua.

The University of Padua, founded in 1222, is where later Galileo Galilei was a lecturer between 1592 and 1610.

I was fortunate enough to pay a 2nd visit to Padova recently. I’d been once before, at least 30 years ago, just to see the Giotto frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel. I had crystal clear, bright blue memories of that chapel and it has been high time, for some time, to pay another visit. So off I went. It was wonderful.

The main goal of my recent trip to Padua was to again see the Giotto frescoes. Nowadays, with the continual press on all the cultural monuments in Italy due to mass tourism and inane “bucket lists,” many sites have time limits on how long you can see the art. The Scrovegni Chapel has joined that rank.

You must book your visit at a particular time well in advance, arrive early to pick up your ticket, meet 10 mins before your time, be ushered into a waiting room and watch a (very interesting) film in Italian while you are “dehumidified”. Is this hocus pocus? I don’t know. But it’s fine.

The only issue I have is that you now enter the chapel with 19 other dehumidified persons and get to stay in the chapel for 15 minutes only and then you are ushered out and the next group is ushered in.

But, before discussing the sublime Scrovegni Chapel, let me say a few words about the archaeological museum that is next door to the chapel.

In fact, the truth is that prior to my recent visit, I had not realized there was an archaeological museum in Padova, let alone attached to the same complex of buildings. And I certainly did not know that Padova was home to such an amazing collection.

I arrived at the Scrovegni Chapel about 45 minutes early and checked in and got my ticket for my 1:00 o’clock visit. The pleasant woman at the check-in desk suggested that I visit the museum when I was thinking aloud, hmmm…I wonder what I should do for the 45 minutes while I wait to visit the chapel.

I am so glad she made that suggestion. I am already planning another visit to Padova later this fall, and you can bet that I’ll be spending a lot more time at this fine museum. Below are just a few pictures from my initial visit.

So…have you ever wondered what the inside of an Egyptian sarcophagus looks like? I have. Fortunately, the Padova museum exhibits one of their sarcophagi open, making both the outside and inside visible. Fascinating.

The Musei Civici has many areas of collection and I just snapped some random pictures of some of the objets that caught my eye. For example, I want to wear the headdress in this painting:

Painting above: Young Woman in Oriental Clothes by Ginevra Cantofoli, Bologna 1618-1672

Painting above: Young Man with turban by Ginevra Cantofoli, Bologna 1618-1672

Check out the amazing frame on painting below. I’ve seen a lot of frames in my day, but this was a first!

Painting below: Armed Minerva by Pietro Liberi, 1614-87. Born in Padova, died in Venezia. This modest little frame that captured my attention and my heart!

Above, the front and back of a crucifix by Giotto.

Some other strange and/or wonderful works I spied on this visit:

Orazio Marinali, Head of Holofernes

I mean, come on…anatomically correct with a severed spinal cord??

Above and below: Filippo Parodi, Head of Spring, or Flora

Love this one below for the frame, the painting, meh…Baby Bacchus by Marco Liberi. But the frame carver, now that’s a masterpiece!

Likewise for the painting below, I can take or leave the painting (Sebastiano Mazzoni, Portrait of theVenetian Captain), but that frame…!

This marble piece below was freaky, the way it combines 2 angel’s heads, showing them kind of like Siamese twins.

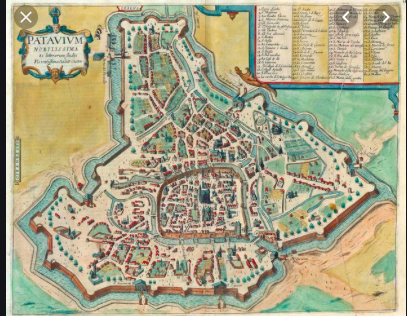

Padova’s historic center is picturesque, with a dense network of arcaded streets opening into large communal piazze, and many bridges crossing the various branches of the Bacchiglione, which once surrounded the ancient walls like a moat.

The city is also known for being the city where Saint Anthony, a Portuguese Franciscan, spent part of his life and died in 1231. The huge pilgrimage church of Sant’ Antonio is a major feature of the city’s life and skyline.

Although I don’t have a clear memory of it, I know I visited the Gattemelata equestrian statue by Donatello on my first visit to Padova. I have clear memories of it from this visit. Here it is:

The name of the city, Padova, is derived from its Roman name Patavium. Its origin is uncertain. It may be connected with the ancient name of the River Po, (Padus). The root “pat-,” in the Indo-European language, can refer to a wide open plain as opposed to nearby hills. The suffix “-av” (also found in the name of the rivers such as the Timavus and Tiliaventum) is likely of Venetic origin, precisely indicating the presence of a river, which in the case of Padua is the Brenta.

Padua claims to be the oldest city in northern Italy. According to a tradition dated at least to the time of Virgil’s Aeneid and to Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita, Padova was founded in around 1183 BC by the Trojan prince Antenor.

After the Fall of Troy, Antenor led a group of Trojans and their Paphlagonian allies, the Eneti or Veneti, who lost their king Pylaemenes to settle the Euganean plain in Italy. Thus, when a large ancient stone sarcophagus was exhumed in the year 1274, officials of the medieval commune declared the remains within to be those of Antenor. An inscription by the native Humanist scholar Lovato dei Lovati placed near the tomb reads:

This sepulchre excavated from marble contains the body of the noble Antenor who left his country, guided the Eneti and Trojans, banished the Euganeans and founded Padua.

More recent tests suggest the sepulchre dates to the between the 4th and 3rd centuries BC.

Nevertheless, archeological remains confirm an early date for the foundation of the center of the town to between the 11th and 10th centuries BC. By the 5th century BC, Padova rose on the banks of the river Brenta and was one of the principal centers of the Veneti.

The Roman historian Livy records an attempted invasion by the Spartan king Cleonimos around 302 BC. The Spartans came up the river but were defeated by the Veneti in a naval battle and gave up the idea of conquest.

Still later, the Veneti of Padua successfully repulsed invasions by the Etruscans and Gauls. According to Livy and Silius Italicus, the Veneti, including those of Padova, formed an alliance with the Romans by 226 BC against their common enemies, first the Gauls and then the Carthaginians. Men from Padova fought and died beside the Romans at Cannae.

With Rome’s northwards expansion, Padova was gradually assimilated into the Roman Republic. In 175 BC, Padova requested the aid of Rome in putting down a local civil war. In 91 BC, Padova, along with other cities of the Veneti, fought with Rome against the rebels in the Social War.

Around 49 (or 45 or 43) BC, Padova was made a Roman municipium under the Lex Julia Municipalis and its citizens ascribed to the Roman tribe, Fabia. At that time the population of the city was perhaps 40,000.

The city was reputed for its excellent breed of horses and the wool of its sheep. In fact, the poet Martial remarks on the thickness of the tunics made there. By the end of the 1st century BC, Padova seems to have been the wealthiest city in Italy outside of Rome.

The city became so powerful that it was reportedly able to raise two hundred thousand fighting men. However, despite its wealth, the city was also renowned for its simple manners and strict morality. This concern with morality is reflected in Livy’s Roman History (XLIII.13.2) wherein he portrays Rome’s rise to dominance as being founded upon her moral rectitude and discipline.

Still later, Pliny, referring to one of his Padovan protégés’ grandmother, Sarrana Procula, lauds her as more upright and disciplined than any of her strict fellow citizens (Epist. i.xiv.6).

Padova also provided the Empire with notable intellectuals. Nearby Abano was the birthplace, and after many years spent in Rome, the deathplace of Livy, whose Latin was said by the critic Asinius Pollio to betray his Patavinitas (q.v. Quintilian, Inst. Or. viii.i.3). Padova was also the birthplace of Thrasea Paetus, Asconius Pedianus, and perhaps Valerius Flaccus.

Christianity was introduced to Padua and much of the Veneto by Saint Prosdocimus. He is venerated as the first bishop of the city. His deacon, the Jewish convert Daniel, is also a saintly patron of the city.

The history of Padua during Late Antiquity follows the course of events common to most cities of north-eastern Italy. Padua suffered from the invasion of the Huns and was savagely sacked by Attila in 450. A number of years afterward, it fell under the control of the Gothic kings Odoacer and Theodoric the Great.

It was reconquered for a short time by the Byzantine Empire in 540 during the Gothic War. However, depopulation from plague and war ensued.

The city was again seized by the Goths under Totila, but was restored to the Eastern Empire by Narses only to fall under the control of the Lombards in 568. During these years, many of Paduans sought safety in the countryside and especially in the nearby lagoons of what would become Venice.

In 601, the city rose in revolt against Agilulf, the Lombard king who put the city under siege. After enduring a 12-year-long bloody siege, the Lombards stormed and burned the city. Many ancient artifacts and buildings were seriously damaged.

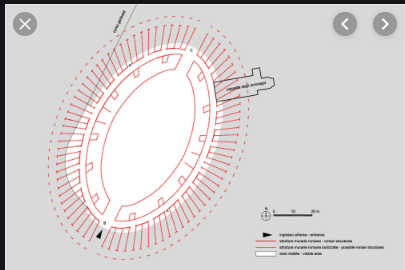

The remains of an amphitheater (the Arena) and some bridge foundations are all that remain of Roman Padua today. The townspeople fled to the hills and later returned to eke out a living among the ruins; the ruling class abandoned the city for the Venetian Lagoon, according to a chronicle. The city did not easily recover from this blow, and Padua was still weak when the Franks succeeded the Lombards as masters of northern Italy.

At the Diet of Aix-la-Chapelle (828), the duchy and march of Friuli, in which Padova lay, was divided into four counties, one of which took its title from the city of Padova.

The end of the early Middle Ages at Padova was marked by the sack of the city by the Magyars in 899. It was many years before Padua recovered from this ravage.

During the period of episcopal supremacy over the cities of northern Italy, Padova does not appear to have been either very important or very active. The general tendency of its policy throughout the war of investitures was Imperial (Ghibelline) and not Roman (Guelph); and its bishops were, for the most part, of German extraction.

However, under the surface, several important movements were taking place that were to prove formative for the later development of Padova.

At the beginning of the 11th century, the citizens established a constitution, composed of a general council or legislative assembly and a credenza or executive body.

During the next century they were engaged in wars with Venice and Vicenza for the right of water-way on the Bacchiglione and the Brenta. The city grew in power and self-confidence and in 1138, government was entrusted to two consuls.

The great families of Camposampiero, Este and Da Romano began to emerge and to divide the Paduan district among themselves. The citizens, in order to protect their liberties, were obliged to elect a podestà in 1178. Their choice first fell on one of the Este family.

A fire devastated Padua in 1174. This required the virtual rebuilding of the city.

The temporary success of the Lombard League helped to strengthen the towns. However, their civic jealousy soon reduced them to weakness again. As a result, in 1236 Frederick II found little difficulty in establishing his vicar Ezzelino III da Romano in Padua and the neighboring cities, where he practised frightful cruelties on the inhabitants. Ezzelino was unseated in June 1256 without civilian bloodshed, thanks to Pope Alexander IV.

Padova then enjoyed a period of calm and prosperity: the basilica of the saint was begun; and the Paduans became masters of Vicenza. The University of Padua (the second university in Italy, after Bologna) was founded in 1222, and as it flourished in the 13th century, Padua outpaced Bologna, where no effort had been made to expand the revival of classical precedents beyond the field of jurisprudence, to become a center of early humanist researches, with a first-hand knowledge of Roman poets that was unrivaled in Italy or beyond the Alps.

There is so much more to the story of Padova. I’ll be posting about it soon.

Pingback: The wonders of Padua (Padua, part 3) | get back, lauretta!