A visit on a gorgeous day to the Abbazia di Monte Oliveto Maggiore in Tuscany is about as good a day trip as I can think of. Leaving Florence on a soft, summer morning, it is a pleasure to drive through beautiful countryside. And once you reach the historic abbey itself, you’ve reached a little piece of heaven.

This large Benedictine monastery is constructed mostly of red brick, making it stand out against the grey clayey and sandy soil of the the Crete senesi, which give this area of Tuscany its name.

The territorial abbey’s abbot functions as the bishop of the land within the abbey’s possession, even though he is not consecrated as a bishop. It is also the mother-house of the Olivetans and the monastery later took the name of Monte Oliveto Maggiore (“the greater”) to distinguish it from successive monasteries at Florence, San Gimignano, Naples and elsewhere.

It was founded in 1313 by Bernardo Tolomei, a jurist from a prominent aristocratic family of Siena. By 1320, it was approved by Bishop Guido Tarlati as Monte Oliveto, with reference to the Mount of Olives and in honor of Christ’s Passion. The monastery was begun in 1320, the new congregation being approved by Pope Clement VI in 1344.

The abbey was for centuries one of the main land possessors in the Siena region. On January 18, 1765, the monastery was made the seat of the Territorial Abbacy of Monte Oliveto Maggiore.

The monastery consists of a medieval palace in red brickwork, surmounted by a massive quadrangular tower with barbicans and merlons. Begun in 1393 as the fortified gate of the complex, it was completed in 1526 and restored in the 19th century. The church’s atrium is on the site of a previous church (1319). The Latin cross formed church was renovated in the Baroque style in 1772 by Giovanni Antinori.

A long alley with cypresses, sided by the botanical garden of the old pharmacy (destroyed in 1896), with a cistern from 1533. At the alley’s end is the bell tower, in Romanesque-Gothic style, and the apse of the church, which has a Gothic façade.

The abbey’s monastic library, housing some 40,000 volumes and incunabula, gives way to the pharmacy, which houses medicinal herbs in a collection of 17th century vases.

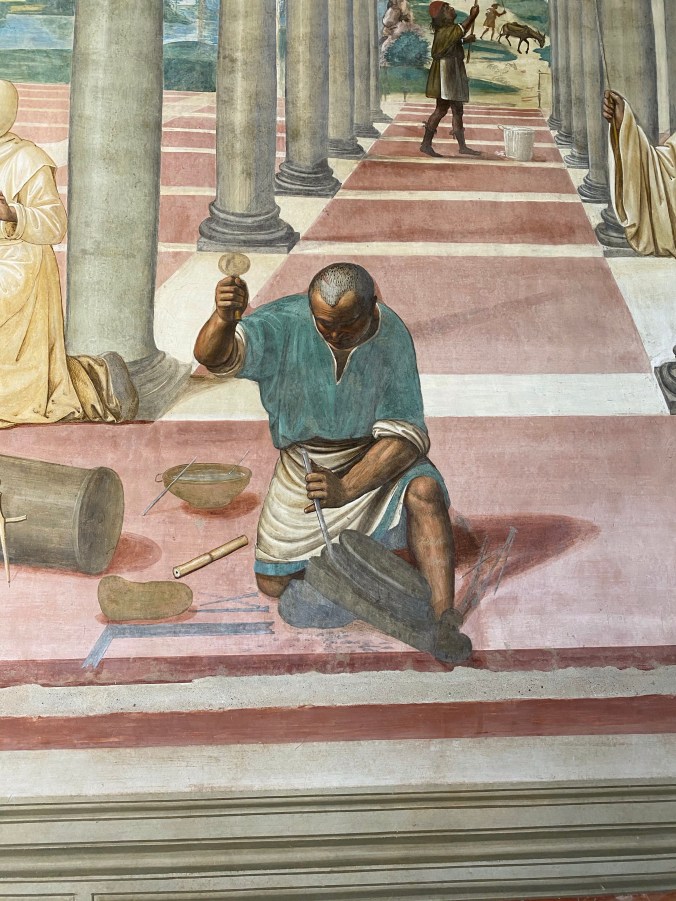

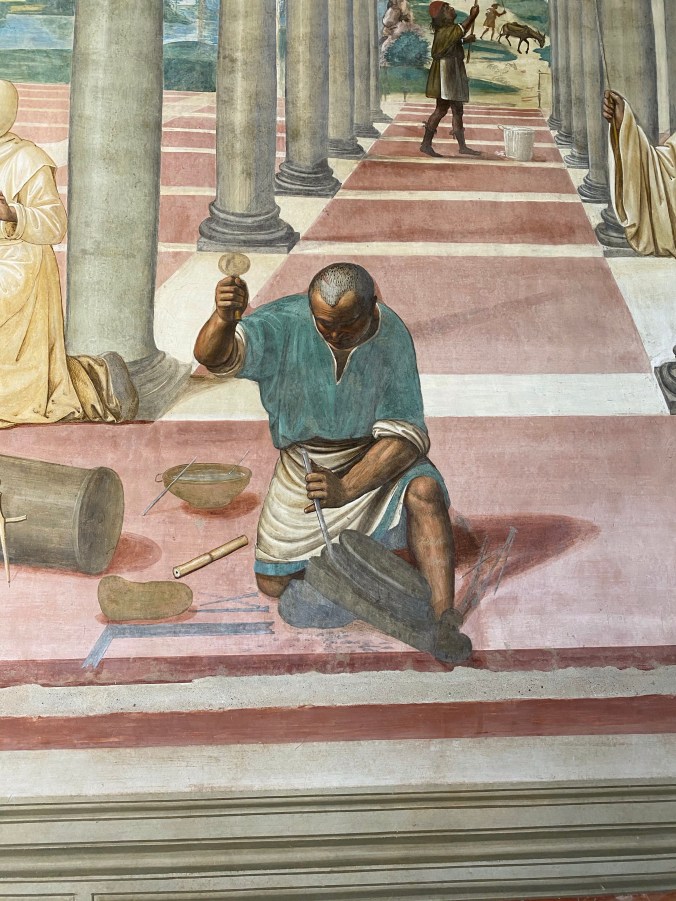

For me, the rectangular Chiostro Grande was the highlight of the visit. The fresco cycle that adorns the walls of the lovely cortile was painted by Luca Signorelli (he created 8 lunettes between 1497-98) and Sodoma, who completed the cycle after 1505. Sodoma painted 26 of the lunettes.

The cloister was constructed between 1426 and 1443. The notable fresco cycle of the Life of St. Benedict was painted between 1497 and 1510 by Luca Signorelli and il Sodoma.

Wikipedia has an excellent article on these frescoes, telling you the entire program of the frescoes and which artist painted which scenes.

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storie_di_san_Benedetto_di_Monte_Oliveto_Maggiore

Luca Signorelli (c. 1445-1523) was an Italian Renaissance painter who was noted in particular for his draftsmanship and his deft handling of foreshortening. His massive frescoes of the Last Judgment (1499–1503) in Orvieto Cathedral are considered his masterpiece. Considered to be part of the Tuscan school, Signorelli also worked extensively in Umbria and Rome.

In the Monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore Signorelli painted eight frescoes, forming part of a vast series depicting the life of St. Benedict; they are not in great condition.

Luca Signorelli, dettaglio di San Benedetto rimprovera due monaci che hanno violato la Regola

Il Sodoma (1477 – 1549) was the strange nickname given to the Italian Renaissance painter Giovanni Antonio Bazzi. Il Sodoma painted in a manner that superimposed the High Renaissance style of early 16th-century Rome onto the traditions of the provincial Sienese school; he spent the bulk of his professional life in Siena, with two periods in Rome.

Sodoma was one of the first to paint in the style of the High Renaissance in Siena. His first important works were these frescoes in the Benedictine monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, on the road from Siena to Rome. The frescoes illustrate the life of St Benedict in continuation of the series that Luca Signorelli had begun in 1498. Gaining fluency in the prevailing popular style of Pinturicchio, Sodoma completed the set in 1502 and included a self-portrait with badgers and ravens.

Autoritratto del Sodoma in un dettaglio da uno degli affreschi delle Storie di san Benedetto di Monte Oliveto Maggiore

The fresco above is by Sodoma, showing Benedict leaving the Roman school.

The fresco above is by Sodoma. It shows a Roman monk giving the hermit habit to Benedict.

The fresco above, by Sodoma, shows the devil breaking the bell.

Above, by Sodoma, shows Benedict as a god-inspired priest bringing food to blessed on Easter.

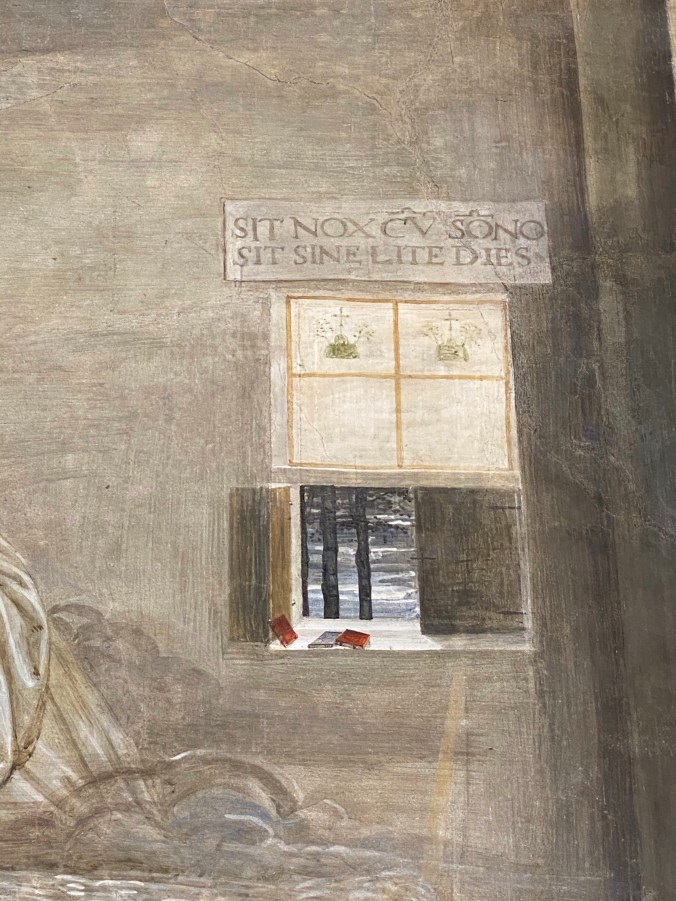

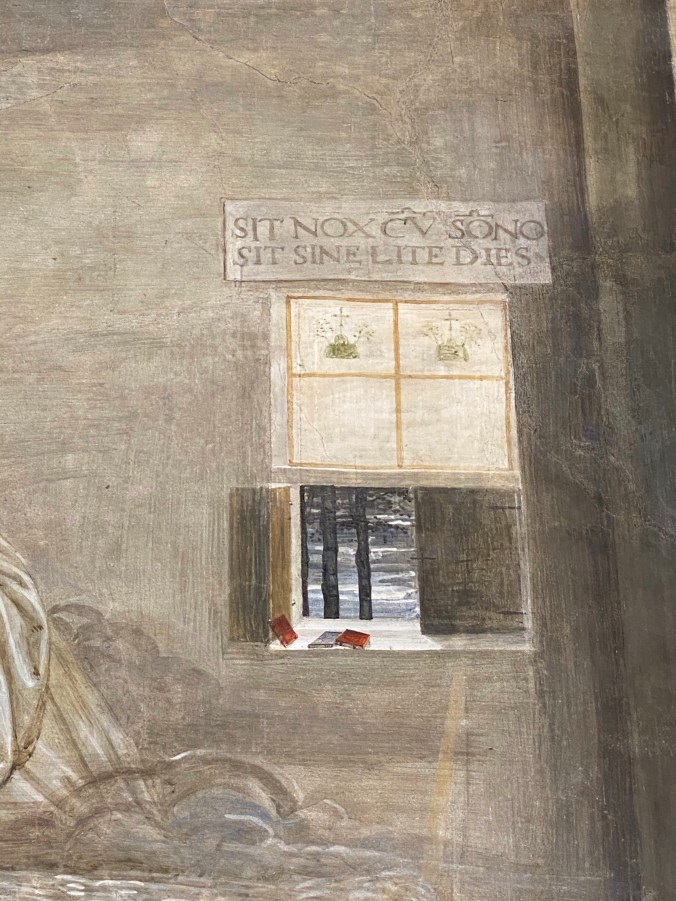

Love the window in this lunette.

In this lunette, above and below, painted by Sodoma, shows How he blessed the building of twelve monasteries.

The painting below is by Signorelli and depicts Benedict talking to the monks after they had eaten outside the monastery

Below: How Benedict discovers Totila’s fiction. In the scene Riggo is seen, disguised as Totila to deceive Benedetto, who arrived in front of the figure of the saint who invites him to take off his clothes; the crowd around composed of monks and warriors expresses his amazement; in the background Riggo tells the story to Totila. It is a crowded scene and set to a theatrical taste [2].

In the scene Riggo is seen, disguised as Totila to deceive Benedetto, who arrived in front of the figure of the saint who invites him to take off his clothes; the crowd around composed of monks and warriors expresses his amazement; in the background Riggo tells the story to Totila. It is a crowded scene and set to a theatrical taste [2].

How Benedict recognizes and welcomes Totila

How Benedict gets plenty of flour and restores the monks

How Benedict appears to two distant monks and he designs the construction of a monastery.

The scene takes place in two stages. On the left the saint appears to one of the two sleeping monks while on the right the work is accomplished

Like Benedict, he excommunicates two nuns and then acquits them that they were dead

Inside a church during the celebration of a mass; to the deacon’s words: If anyone is excommunicated, go out, a woman sees two nuns excommunicated by Saint Benedict come out of the tomb. On the right, in small, the saint reconciles the nuns

And, last, but not least, the modern incursion into the abbey. A garage where there used to be a stable. Complete with frescoes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.