The Saracen joust of Arezzo (Giostra del Saracino, Giostra ad burattum) is an ancient game of chivalry, dating back to the Middle Ages and born as an exercise for military training.

The game acquired an important social function within the urban community: it was used to commemorate great public events, such as during the visit of important sovereigns or princes, and was also used to make certain civil feasts more solemn (carnivals and local aristocratic weddings).

The joust – which became a typical tradition of Arezzo at the beginning of the 17th century – declined progressively during the 18th century and eventually disappeared, at least in its “noble” version. After a brief popular revival between the 18th and 19th century, the joust was interrupted after 1810 to reappear only in 1904 in the wake of the Middle Ages reappraisal. The joust was restored in 1931 as a form of historical re-enactment set in the 14th century, and quickly acquired a competitive character.

The historical reenactment takes place every year in Arezzo on one Saturday night in June (the so-called San Donato Joust, dedicated to the patron saint of the town) and on the afternoon of the first Sunday of September.

The teams in the event are the four quarters of the town of Arezzo:

- Porta Crucifera, known as Culcitrone (green and red),

- Porta del Foro, known as Porta San Lorentino (yellow and crimson),

- Porta Sant’Andrea (white and green)

- Porta del Borgo, today called Porta Santo Spirito (yellow and blue).

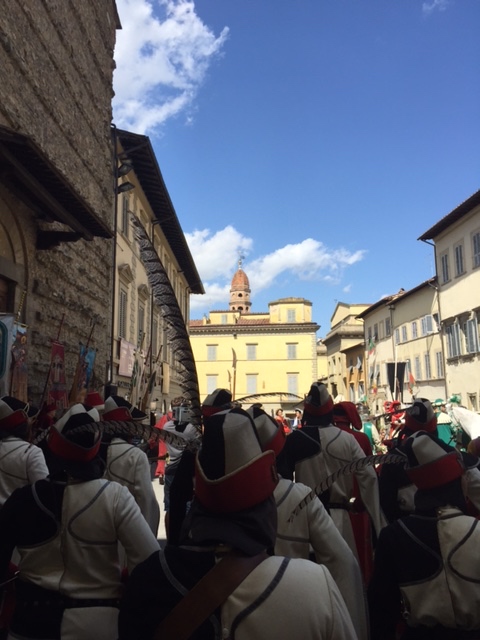

The jousting day starts in the morning, when the town’s Herald reads the proclamation of the joust challenge, and then continues with a colorful procession of 350 costume characters and 27 horses parading along the streets of Arezzo. The highlight of the parade, which is given by the Bishop of Arezzo and takes place on the steps of the Duomo, is the blessing of the men-at-arms and their horses.

The knights’ tournament is held in the Piazza Grande, guided by the Maestro di Campo and preceded by the costumed characters and the town’s ancient banners entering the square, accompanied by the sound of trumpets and drums. The highest authorities of the Joust enter the square (the magistrates, the Jury, the quarters’ presidents), the performance of flag-wavers, the jousters galloping into the racing field, each knight representing an ancient noble family of Arezzo, the knights’ arrangement on the lizza (jousting track), the Herald reading the Challenge of Buratto (a poetic composition written in octaves in the 17th century), the crossbowmen and the soldiers greeting the crowd shouting “Arezzo!”, the magistrates’ authorization to run the joust and finally the Joust’s musicians playing the Saracen Hymn, composed by Giuseppe Pietri (1886–1946).

Then, the real competition starts. The jousters of the four gates gallop their horses with lance in rest against the Saracen, an armor-plated dummy representing a Saracen (“Buratto, King of the Indies”) holding a cat-o’-9-tails. The sequence of charges is drawn on the week preceding the joust during a costumed ceremony in Piazza del Comune. It’s almost impossible to foresee the result of the joust will be: it depends on the ability, the courage and the good-luck of the eight jousters who alternate on the packed-earth sloping track (the lizza) that runs transversally across Piazza Grande.

The competition is won by the couple of knights who hit the Saracen’s shield obtaining the higher scores. The quarter associated to the winning knight receives the coveted golden lance. In the event of a draw between two or more quarters after the standard number of charges (two sets of charges for each jouster), the prize is assigned with one or more deciding charges. At the end of the joust, mortar shots hail the winning quarter.

The rules of the tournament are contained in technical regulations that repeat – virtually unchanged – the Chapters for the Buratto Joust dating back to 1677. They are easy to understand, and yet worded in such a way as to guarantee a long-lasting suspense. The outcome of the fight between the Christian knights and the “Infidel” is undecided until the very last moment due to dramatic turns of events. For instance, jousters may be disqualified if they ride accidentally off the jousting track, or their scores may be doubled if their lance breaks after violently hitting the Saracen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.