source:

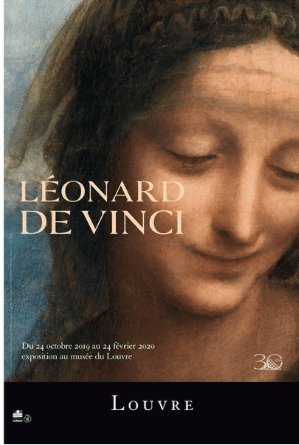

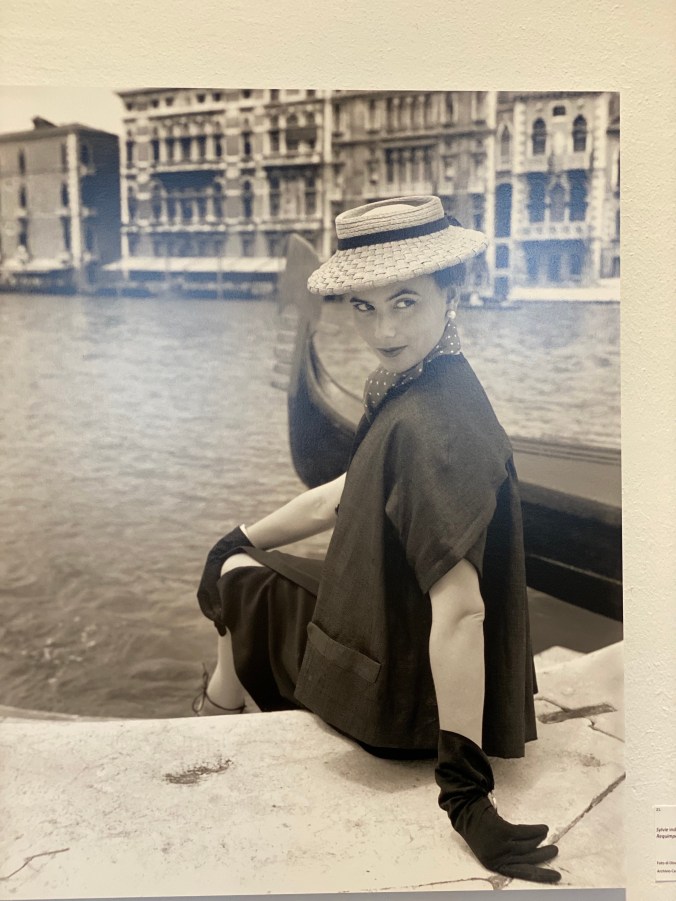

This lovely little exhibition, entitled Timeless Elegance, Dior in Venice in the Cameraphoto Archives, is currently on display at Villa Pisani, in Stra, on the Brenta Canal in the Veneto. I enjoyed seeing it very much.

From the website of the Villa:

1951 was a magical year for Venice. Some of the most intriguing views of the city co-starred in the campaign that publicised the creations of the couturier who was capturing all the world’s headlines at the time: Christian Dior.

On 3 September of that same year, Palazzo Labia hosted the “Ball of the Century”: the Bal Oriental, organised by Don Carlos de Beistegui y de Yturbe, attracted around a thousand glittering jetsetters from all five continents. This masked ball saw Dior, Dalí, a very young Cardin, Nina Ricci and others engaged as creators of costumes for the illustrious guests, in an event that made the splendour of eighteenth-century Venice reverberate around the world.

Silent witnesses of both of these events were the photographers of Cameraphoto, the photography agency founded in 1946 by Dino Jarach, who covered and recorded everything special that happened in Venice and beyond during those years.

We have Vittorio Pavan, the current conservator of the imposing Cameraphoto Archives (the historical section alone has more than 300,000 negatives on file) and Daniele Ferrara, Director of the Veneto Museums Hub, to thank for the project to show the photographs of those two historical events to the general public. The location chosen for them to re-emerge into the light of day is one of extraordinary significance: Villa Nazionale Pisani in Stra is the Queen of the Villas of the Veneto and it is no coincidence that it is adorned with marvellous frescoes by Giambattista Tiepolo, the same artist whose work also gazed down on the unforgettable masked ball in 1951 from the ceilings of Palazzo Labia.

For this exhibition, Pavan has chosen 40 photographs of the collection shown in Venice by Christian Dior.

In those days, every fashion show would present just under 200 models, calculated carefully to achieve the right balance between items that would be easy to wear and others that made more of a statement. Dior was the undisputed master of fashion in those post-war years. The whole world looked forward to his collections and discussed them hotly. No fewer than 25,000 people are estimated to have crossed the Atlantic every year, just to see (and to buy) his collections. Every time he changed a line (and every new season brought such a change), it was accepted with both enthusiasm and ferocious criticism: the former from his clan of admirers, the latter from those who opposed him.

In any case, no woman who aspired to keep abreast of fashion could afford to ignore the dictates issued by the couturier from his Parisian maison in Avenue Montaigne, where he already employed a staff of more than one thousand, despite having being established only five years before. Dior’s New look evolved with every passing season.

In 1950, he introduced the Vertical Line, in 1951 – as the photographs on show in Villa Pisani illustrate – no woman could avoid wearing his Oval Look: rounded shoulders and raglan sleeves, the fabrics modelled until they clung like a second skin. The essential accessory was of course the hat, for which Dior that year drew his inspiration from the kind traditionally worn by Chinese coolies.

For that autumn, though, he created the Princess line, which gave the illusion of extending below the breast.

In the breathtaking photographs from the Cameraphoto Archives, beautiful Dior-clad models perform a virtual duet with Venice, whose canals, churches and palaces are never a mere backdrop, but co-stars on a par with the great designer’s creations.

The second nucleus of this fascinating exhibition is devoted to the Grand Ball at Palazzo Labia, possibly the most glittering social event of the century.

All the bel monde flocked to Venice on that legendary 3 September. Don Carlos, popularly known as the Count of Monte Cristo, sent personal invitations to a thousand people. Dior, together with a veritable army of young tailors and accompanied by Dalí, was engaged to create the most alluring costumes, all designed to refer to the eighteenth century when Goldoni and Casanova lived here. There were costumes for men and women, but also for the greyhounds and other dogs that often accompanied their owners.

The torches that on that legendary evening illuminated the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, several Grandees of Spain, the Aga Khan, King Farouk of Egypt, Winston Churchill, many crowned heads, princes and princesses, a host of millionaires, such artists as Fabrizio Clerici and Leonor Fini, fashion designers of the calibre of Balenciaga and Elsa Schiapparelli and leading jetsetters Barbara Hutton, Lady Diana Cooper, Orson Welles, Daisy Fellowes, Cecil Beaton (whose photographs, published in Life magazine, gave the world something to dream about), the Polignacs and the Rothschilds.

Welcoming them in the midst of clouds of ballerinas and harlequins was the master of the house and host, who dominated the scene as he promenaded back and forth dressed as the Sun King on a 40 cm high platform. The heir of an immense fortune created in Mexico, Don Carlos spent some of his time living in Paris, where he owned a house designed by Le Corbusier and decorated by Salvador Dalí, and the rest at a chateau in the country. He had bought Palazzo Labia and restored it and was now offering it to his friends.

The aim of this exhibition is therefore to contribute to improving the appreciation and value of the Cameraphoto photography archives, which have been declared to be of exceptional cultural interest by the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, since they constitute an inestimable legacy for the wealth and variety of images.

It was with this in mind that the curators chose this nucleus of photographs depicting the clothing designed by one of the most ingenious and iconic fashion designers in history, who in his turn, through his creations, enabled a spotlight to be focused on a tiny fragment of the more than one thousand years of history of the city of Venice, helping us reconstruct the collective memory on which our present day is based.

Curated by Vittorio Pavan and Luca Del Prete, the exhibition is organised by the Veneto Museums Hub e Munus.

I recently posted about this day-long cruise here (here, here and here) and now I pick up where I left off. Our first stop on the cruise after leaving Padua was in Stra at Villa Pisani. This incredible villa is now a state museum and very much work a visit. It was built by a very popular Venetian Doge.

The facade of the Villa is decorated with enormous statues and the interior was painted by some of the greatest artists of the 18th century.

Villa Pisani at Stra refers is a monumental, late-Baroque rural palace located along the Brenta Canal (Riviera del Brenta) at Via Doge Pisani 7 near the town of Stra, on the mainland of the Veneto, northern Italy. This villa is one of the largest examples of Villa Veneta located in the Riviera del Brenta, the canal linking Venice to Padua. It is to be noted that the patrician Pisani family of Venice commissioned a number of villas, also known as Villa Pisani across the Venetian mainland. The villa and gardens now operate as a national museum, and the site sponsors art exhibitions.

Construction of this palace began in the early 18th century for Alvise Pisani, the most prominent member of the Pisani family, who was appointed doge in 1735.

The initial models of the palace by Paduan architect Girolamo Frigimelica still exist, but the design of the main building was ultimately completed by Francesco Maria Preti. When it was completed, the building had 114 rooms, in honor of its owner, the 114th Doge of Venice Alvise Pisani.

In 1807 it was bought by Napoleon from the Pisani Family, now in poverty due to great losses in gambling. In 1814 the building became the property of the House of Habsburg who transformed the villa into a place of vacation for the European aristocracy of that period. In 1934 it was partially restored to host the first meeting of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, after the riots in Austria.

From the outside, the facade of the oversized palace appears to command the site, facing the Brenta River some 30 kilometers from Venice. The villa is of many villas along the canal, which the Venetian noble families and merchants started to build as early as the 15th century. The broad façade is topped with statuary, and presents an exuberantly decorated center entrance with monumental columns shouldered by caryatids. It shelters a large complex with two inner courts and acres of gardens, stables, and a garden maze.

The largest room is the ballroom, where the 18th-century painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo frescoed the two-story ceiling with a massive allegorical depiction of the Apotheosis or Glory of the Pisani family (painted 1760–1762).[2] Tiepolo’s son Gian Domenico Tiepolo, Crostato, Jacopo Guarana, Jacopo Amigoni, P.A. Novelli, and Gaspare Diziani also completed frescoes for various rooms in the villa. Another room of importance in the villa is now known as the “Napoleon Room” (after his occupant), furnished with pieces from the Napoleonic and Habsburg periods and others from when the house was lived by the Pisani.

The most riotously splendid Tiepolo ceiling would influence his later depiction of the Glory of Spain for the throne room of the Royal Palace of Madrid; however, the grandeur and bombastic ambitions of the ceiling echo now contrast with the mainly uninhabited shell of a palace. The remainder of its nearly 100 rooms are now empty. The Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni described the palace in its day as a place of great fun, served meals, dance and shows.

Check out this sunken bathtub below:

Bear with me: in the next few photos I am trying out all of the fancy settings on my new camera:

To be continued.

I had to go back to Padua to see the masterpiece of Medieval fresco painting and I’m so happy I did. One, two, even three times in a lifetime is not enough. I’m now at 4 times and counting.

Tuscan sculptor, Giovanni Pisano, is also well-represented in the chapel.

The brochure for the Chapel tells us this about the Scrovegni Chapel: “In 1300, the rich nobleman Enrico Scrovegni acquired the area of the Roman Arena [in Padova], on which he intended to build a fine town house. Next to it, he had a chapel built and dedicated to the Holy Virgin, for the soul of his father Reginaldo, the usurer mentioned in the 17th canto of Dante’s ‘Inferno.’ Scrovegni commissioned Giotto to decorate the chapel with frescoes which, according to most reliable information, was done between 1303-05. The frescoes cover the interior walls and ceiling of the building completely. The lower part of the blue star-spangled vaulted ceiling depicts the prophets and the important episodes in the lives of the Holy Virgin and Jesus Christ. Above the main door is ‘The Last Judgment:’ Christ, as judge, is surrounded by the angels and the apostles; below him, to the right, are the Blessed; to the left, the Damned are depicted as suffering eternal punishment, according to medieval tradition.”

‘

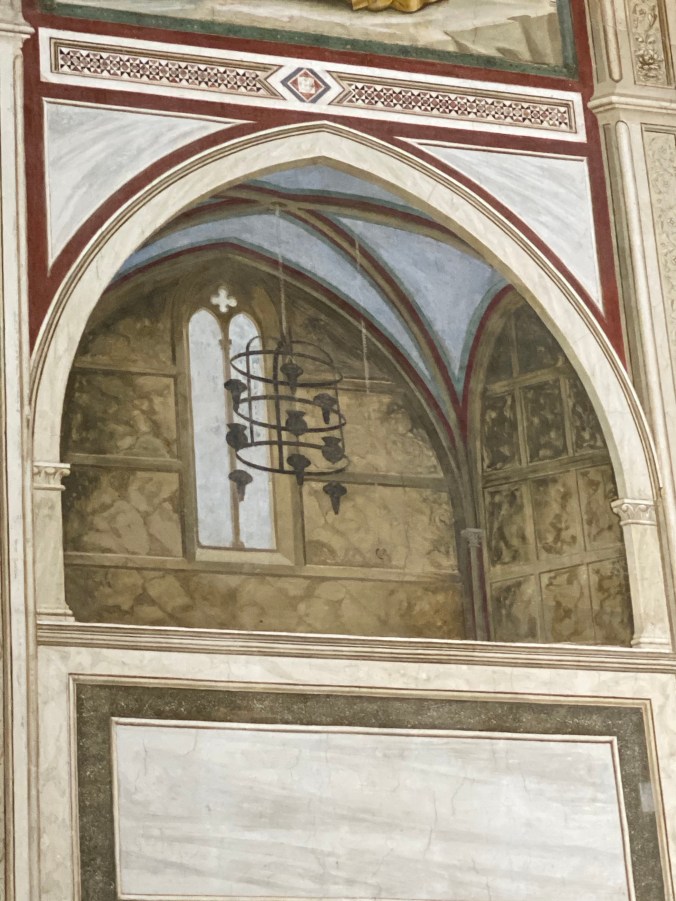

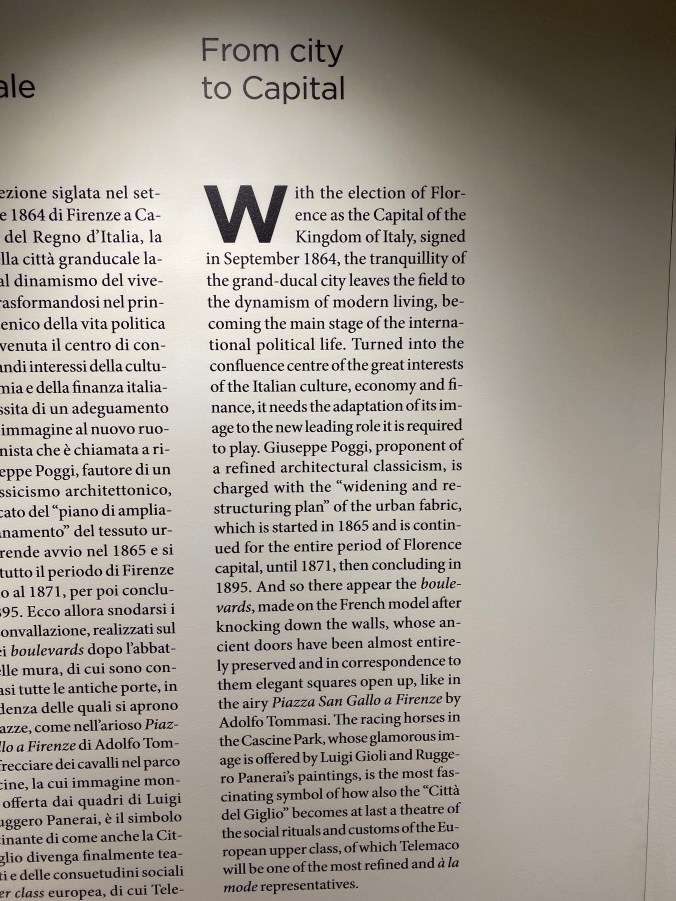

Lovers of the ottocento and of old Florence will love the current exhibition at the Palazzo Antinori. Entitled “The Florence of Giovanni and Telemaco Signorini” (father and son), the show runs through 10 November 2019. For people like me, it is a delightful experience to not only see the show, but to also have a look at the piano nobile of the Antinori Palace.

The exhibition also includes a few paintings by contemporaries of the Signorini father/son painters. It includes: Ruggero Panerai, Luigi Gioli, Francesco Gioli, Giorgio Mignaty, Adolfo Tommasi, and Antonio Puccinelli. There is also a sculpted bust of Telemaco Signorini by Giovanni Dupre.

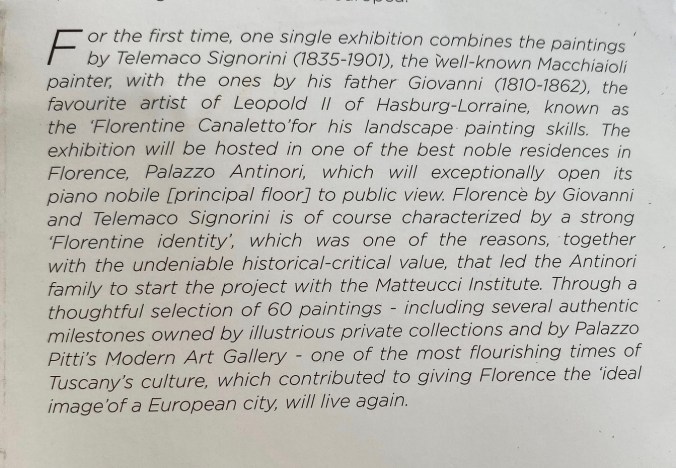

Here’s what the brochure announces about this exhibition:

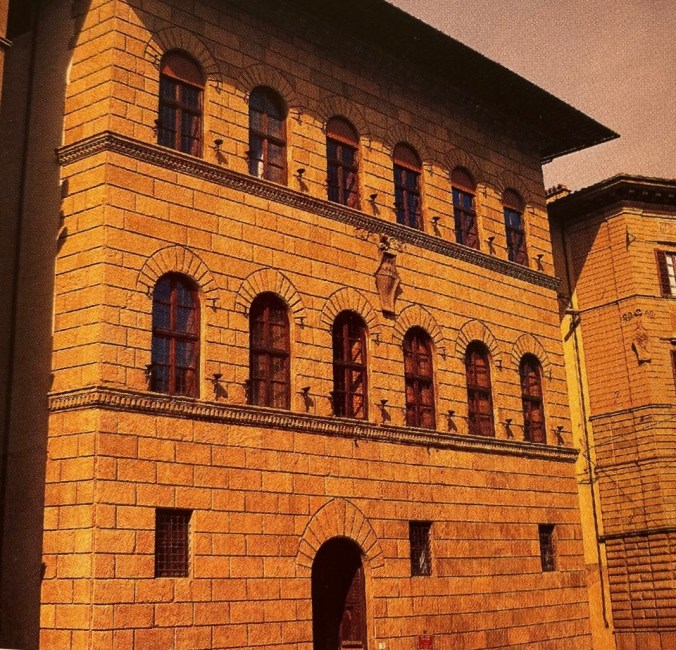

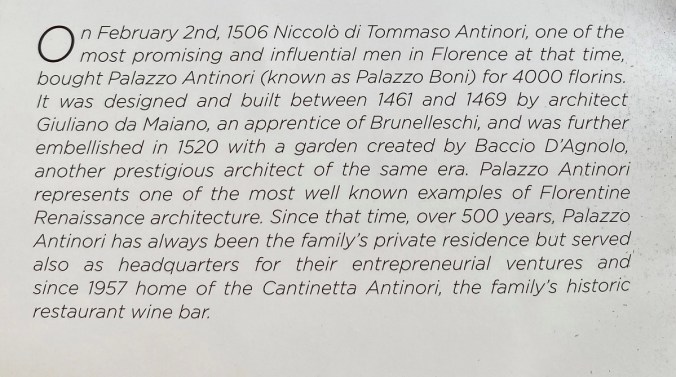

Regarding the beautiful palazzo itself:

Allora, now that I am done being a voyeur for the palazzo itself, let us look at some of the paintings in the exhibition: First up, a few paintings by Giovanni Signorini

Above, Giovanni Signorini, Veduta dell’ Arno da Ponte alla Carraia, 1846

And now, for some paintings by Telemaco Signorini

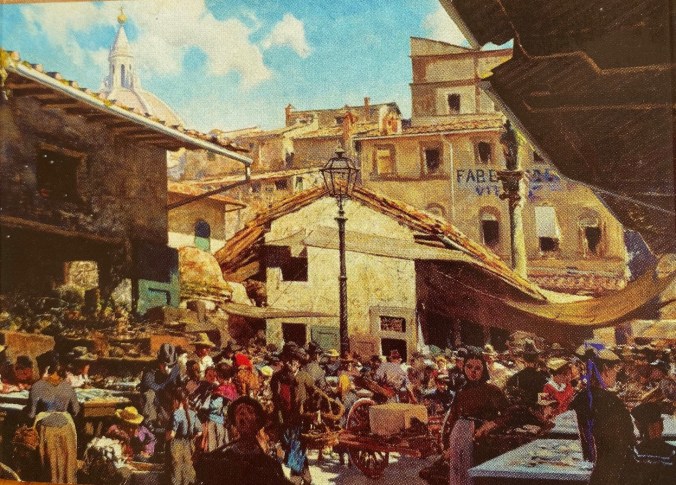

Above: Telemaco Signorini, Mercato Vecchio, 1882-83

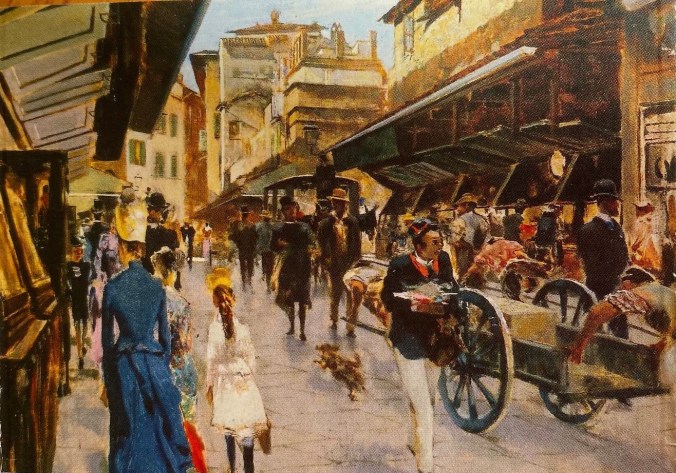

Above: Telemaco Signorini, Il ponte Vecchio a Firenze, 1880

I’ve already written once about my visit to L’orangerie in Paris, but that hardly did justice to this great Parisian museum. So, today I add more.

There’s Renoir:

There’s Cezanne:

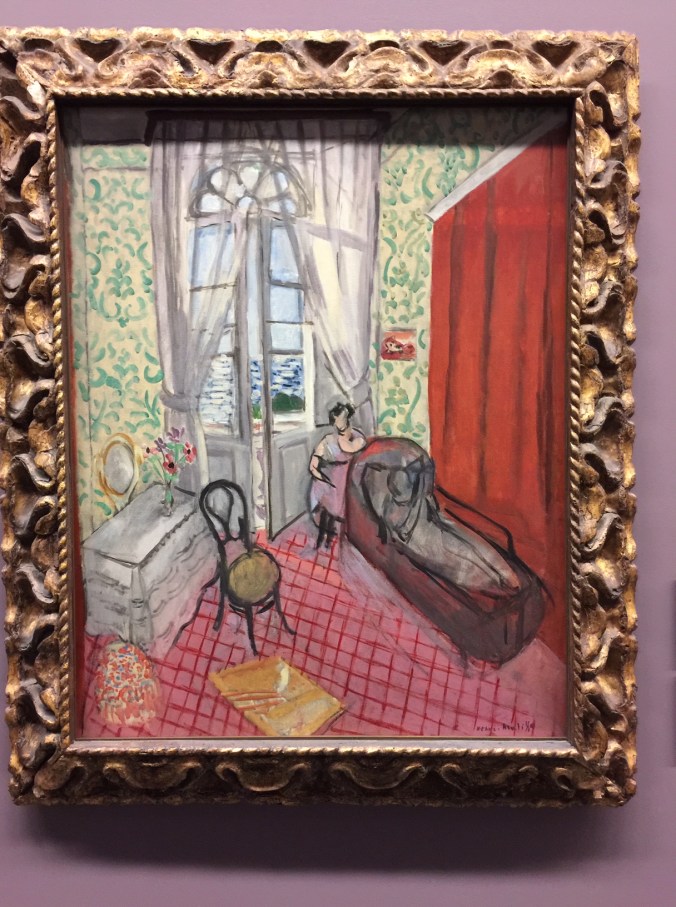

There’s Matisse:

Padova or Padua is a big subject! I’ve recently posted 2 times about it, here, here, here and here. And, still, I am far from done!

This post includes a list of the major features that grace this lovely, historic town. But first, a sweet little video about the town itself:

Undoubtedly the most notable things about Padova is the Giotto masterpiece of fresco painting in the The Scrovegni Chapel (Cappella degli Scrovegni). This incredible cycle of frescoes was completed in 1305 by Giotto.

It was commissioned by Enrico degli Scrovegni, a wealthy banker, as a private chapel once attached to his family’s palazzo. It is also called the “Arena Chapel” because it stands on the site of a Roman-era arena.

The fresco cycle details the life of the Virgin Mary and has been acknowledged by many to be one of the most important fresco cycles in the world for its role in the development of European painting. It is a miracle that the chapel survived through the centuries and especially the bombardment of the city at the end of WWII. But for a few hundred yards, the chapel could have been destroyed like its neighbor, the Church of the Eremitani.

The Palazzo della Ragione, with its great hall on the upper floor, is reputed to have the largest roof unsupported by columns in Europe; the hall is nearly rectangular, its length 267.39 ft, its breadth 88.58 ft, and its height 78.74 ft; the walls are covered with allegorical frescoes. The building stands upon arches, and the upper story is surrounded by an open loggia, not unlike that which surrounds the basilica of Vicenza.

The Palazzo was begun in 1172 and finished in 1219. In 1306, Fra Giovanni, an Augustinian friar, covered the whole with one roof. Originally there were three roofs, spanning the three chambers into which the hall was at first divided; the internal partition walls remained till the fire of 1420, when the Venetian architects who undertook the restoration removed them, throwing all three spaces into one and forming the present great hall, the Salone. The new space was refrescoed by Nicolo’ Miretto and Stefano da Ferrara, working from 1425 to 1440. Beneath the great hall, there is a centuries-old market.

In the Piazza dei Signori is the loggia called the Gran Guardia, (1493–1526), and close by is the Palazzo del Capitaniato, the residence of the Venetian governors, with its great door, the work of Giovanni Maria Falconetto, the Veronese architect-sculptor who introduced Renaissance architecture to Padua and who completed the door in 1532.

Falconetto was also the architect of Alvise Cornaro’s garden loggia, (Loggia Cornaro), the first fully Renaissance building in Padua.

Nearby stands the il duomo, remodeled in 1552 after a design of Michelangelo. It contains works by Nicolò Semitecolo, Francesco Bassano and Giorgio Schiavone.

The nearby Baptistry, consecrated in 1281, houses the most important frescoes cycle by Giusto de’ Menabuoi.

The Basilica of St. Giustina, faces the great piazza of Prato della Valle.

The Teatro Verdi is host to performances of operas, musicals, plays, ballets, and concerts.

The most celebrated of the Paduan churches is the Basilica di Sant’Antonio da Padova. The bones of the saint rest in a chapel richly ornamented with carved marble, the work of various artists, among them Sansovino and Falconetto.

The basilica was begun around the year 1230 and completed in the following century. Tradition says that the building was designed by Nicola Pisano. It is covered by seven cupolas, two of them pyramidal.

Donatello’s equestrian statue of the Venetian general Gattamelata (Erasmo da Narni) can be found on the piazza in front of the Basilica di Sant’Antonio da Padova. It was cast in 1453, and was the first full-size equestrian bronze cast since antiquity. It was inspired by the Marcus Aurelius equestrian sculpture at the Capitoline Hill in Rome.

Not far from the Gattamelata are the St. George Oratory (13th century), with frescoes by Altichiero, and the Scuola di S. Antonio (16th century), with frescoes by Tiziano (Titian).

One of the best known symbols of Padua is the Prato della Valle, a large elliptical square, one of the biggest in Europe. In the center is a wide garden surrounded by a moat, which is lined by 78 statues portraying illustrious citizens. It was created by Andrea Memmo in the late 18th century.

Memmo once resided in the monumental 15th-century Palazzo Angeli, which now houses the Museum of Precinema.

The Abbey of Santa Giustina and adjacent Basilica. In the 5th century, this became one of the most important monasteries in the area, until it was suppressed by Napoleon in 1810. In 1919 it was reopened.

The tombs of several saints are housed in the interior, including those of Justine, St. Prosdocimus, St. Maximus, St. Urius, St. Felicita, St. Julianus, as well as relics of the Apostle St. Matthias and the Evangelist St. Luke.

The abbey is also home to some important art, including the Martyrdom of St. Justine by Paolo Veronese. The complex was founded in the 5th century on the tomb of the namesake saint, Justine of Padua.

The Church of the Eremitani is an Augustinian church of the 13th century, containing the tombs of Jacopo (1324) and Ubertinello (1345) da Carrara, lords of Padua, and the chapel of SS James and Christopher, formerly illustrated by Mantegna’s frescoes. The frescoes were all but destroyed bombs dropped by the Allies in WWII, because it was next to the Nazi headquarters.

The old monastery of the church now houses the Musei Civici di Padova (town archeological and art museum).

Santa Sofia is probably Padova’s most ancient church. The crypt was begun in the late 10th century by Venetian craftsmen. It has a basilica plan with Romanesque-Gothic interior and Byzantine elements. The apse was built in the 12th century. The edifice appears to be tilting slightly due to the soft terrain.

Botanical Garden (Orto Botanico)

The church of San Gaetano (1574–1586) was designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi, on an unusual octagonal plan. The interior, decorated with polychrome marbles, houses a Madonna and Child by Andrea Briosco, in Nanto stone.

The 16th-century Baroque Padua Synagogue

At the center of the historical city, the buildings of Palazzo del Bò, the center of the University.

The City Hall, called Palazzo Moroni, the wall of which is covered by the names of the Paduan dead in the different wars of Italy and which is attached to the Palazzo della Ragione

The Caffé Pedrocchi, built in 1831 by architect Giuseppe Jappelli in neoclassical style with Egyptian influence. This café has been open for almost two centuries. It hosts the Risorgimento museum, and the near building of the Pedrocchino (“little Pedrocchi”) in neogothic style.

There is also the Castello. Its main tower was transformed between 1767 and 1777 into an astronomical observatory known as Specola. However the other buildings were used as prisons during the 19th and 20th centuries. They are now being restored.

The Ponte San Lorenzo, a Roman bridge largely underground, along with the ancient Ponte Molino, Ponte Altinate, Ponte Corvo and Ponte S. Matteo.

There are many noble ville near Padova. These include:

Villa Molin, in the Mandria fraction, designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1597.

Villa Mandriola (17th century), at Albignasego

Villa Pacchierotti-Trieste (17th century), at Limena

Villa Cittadella-Vigodarzere (19th century), at Saonara

Villa Selvatico da Porto (15th–18th century), at Vigonza

Villa Loredan, at Sant’Urbano

Villa Contarini, at Piazzola sul Brenta, built in 1546 by Palladio and enlarged in the following centuries, is the most important

Padua has long been acclaimed for its university, founded in 1222. Under the rule of Venice the university was governed by a board of three patricians, called the Riformatori dello Studio di Padova. The list of notable professors and alumni is long, containing, among others, the names of Bembo, Sperone Speroni, the anatomist Vesalius, Copernicus, Fallopius, Fabrizio d’Acquapendente, Galileo Galilei, William Harvey, Pietro Pomponazzi, Reginald, later Cardinal Pole, Scaliger, Tasso and Jan Zamoyski.

It is also where, in 1678, Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopia became the first woman in the world to graduate from university.

The university hosts the oldest anatomy theatre, built in 1594.

The university also hosts the oldest botanical garden (1545) in the world. The botanical garden Orto Botanico di Padova was founded as the garden of curative herbs attached to the University’s faculty of medicine. It still contains an important collection of rare plants.

The place of Padua in the history of art is nearly as important as its place in the history of learning. The presence of the university attracted many distinguished artists, such as Giotto, Fra Filippo Lippi and Donatello; and for native art there was the school of Francesco Squarcione, whence issued Mantegna.

Padua is also the birthplace of the celebrated architect Andrea Palladio, whose 16th-century villas (country-houses) in the area of Padua, Venice, Vicenza and Treviso are among the most notable of Italy and they were often copied during the 18th and 19th centuries; and of Giovanni Battista Belzoni, adventurer, engineer and egyptologist.

The sculptor Antonio Canova produced his first work in Padua, one of which is among the statues of Prato della Valle (presently a copy is displayed in the open air, while the original is in the Musei Civici).

The Antonianum is settled among Prato della Valle, the Basilica of Saint Anthony and the Botanic Garden. It was built in 1897 by the Jesuit fathers and kept alive until 2002. During WWII, under the leadership of P. Messori Roncaglia SJ, it became the center of the resistance movement against the Nazis. Indeed, it briefly survived P. Messori’s death and was sold by the Jesuits in 2004.

Paolo De Poli, painter and enamellist, author of decorative panels and design objects, 15 times invited to the Venice Biennale was born in Padua. The electronic musician Tying Tiffany was also born in Padua.

Two current exhibitions celebrate this American master.

If you read my post entitled Sad and true, the anti-reforms in Italy’s art world

I have some good news for you. Things have changed for the better!!

Dale Chihuly shows up everywhere! He is a worldwide phenom…

You must be logged in to post a comment.