Popular culture

Villa Pisani: Cruising the Brenta Canal from Padua to Venice, part 2

I recently posted about this day-long cruise here (here, here and here) and now I pick up where I left off. Our first stop on the cruise after leaving Padua was in Stra at Villa Pisani. This incredible villa is now a state museum and very much work a visit. It was built by a very popular Venetian Doge.

The facade of the Villa is decorated with enormous statues and the interior was painted by some of the greatest artists of the 18th century.

Villa Pisani at Stra refers is a monumental, late-Baroque rural palace located along the Brenta Canal (Riviera del Brenta) at Via Doge Pisani 7 near the town of Stra, on the mainland of the Veneto, northern Italy. This villa is one of the largest examples of Villa Veneta located in the Riviera del Brenta, the canal linking Venice to Padua. It is to be noted that the patrician Pisani family of Venice commissioned a number of villas, also known as Villa Pisani across the Venetian mainland. The villa and gardens now operate as a national museum, and the site sponsors art exhibitions.

Construction of this palace began in the early 18th century for Alvise Pisani, the most prominent member of the Pisani family, who was appointed doge in 1735.

The initial models of the palace by Paduan architect Girolamo Frigimelica still exist, but the design of the main building was ultimately completed by Francesco Maria Preti. When it was completed, the building had 114 rooms, in honor of its owner, the 114th Doge of Venice Alvise Pisani.

In 1807 it was bought by Napoleon from the Pisani Family, now in poverty due to great losses in gambling. In 1814 the building became the property of the House of Habsburg who transformed the villa into a place of vacation for the European aristocracy of that period. In 1934 it was partially restored to host the first meeting of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, after the riots in Austria.

From the outside, the facade of the oversized palace appears to command the site, facing the Brenta River some 30 kilometers from Venice. The villa is of many villas along the canal, which the Venetian noble families and merchants started to build as early as the 15th century. The broad façade is topped with statuary, and presents an exuberantly decorated center entrance with monumental columns shouldered by caryatids. It shelters a large complex with two inner courts and acres of gardens, stables, and a garden maze.

The largest room is the ballroom, where the 18th-century painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo frescoed the two-story ceiling with a massive allegorical depiction of the Apotheosis or Glory of the Pisani family (painted 1760–1762).[2] Tiepolo’s son Gian Domenico Tiepolo, Crostato, Jacopo Guarana, Jacopo Amigoni, P.A. Novelli, and Gaspare Diziani also completed frescoes for various rooms in the villa. Another room of importance in the villa is now known as the “Napoleon Room” (after his occupant), furnished with pieces from the Napoleonic and Habsburg periods and others from when the house was lived by the Pisani.

The most riotously splendid Tiepolo ceiling would influence his later depiction of the Glory of Spain for the throne room of the Royal Palace of Madrid; however, the grandeur and bombastic ambitions of the ceiling echo now contrast with the mainly uninhabited shell of a palace. The remainder of its nearly 100 rooms are now empty. The Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni described the palace in its day as a place of great fun, served meals, dance and shows.

Check out this sunken bathtub below:

Bear with me: in the next few photos I am trying out all of the fancy settings on my new camera:

To be continued.

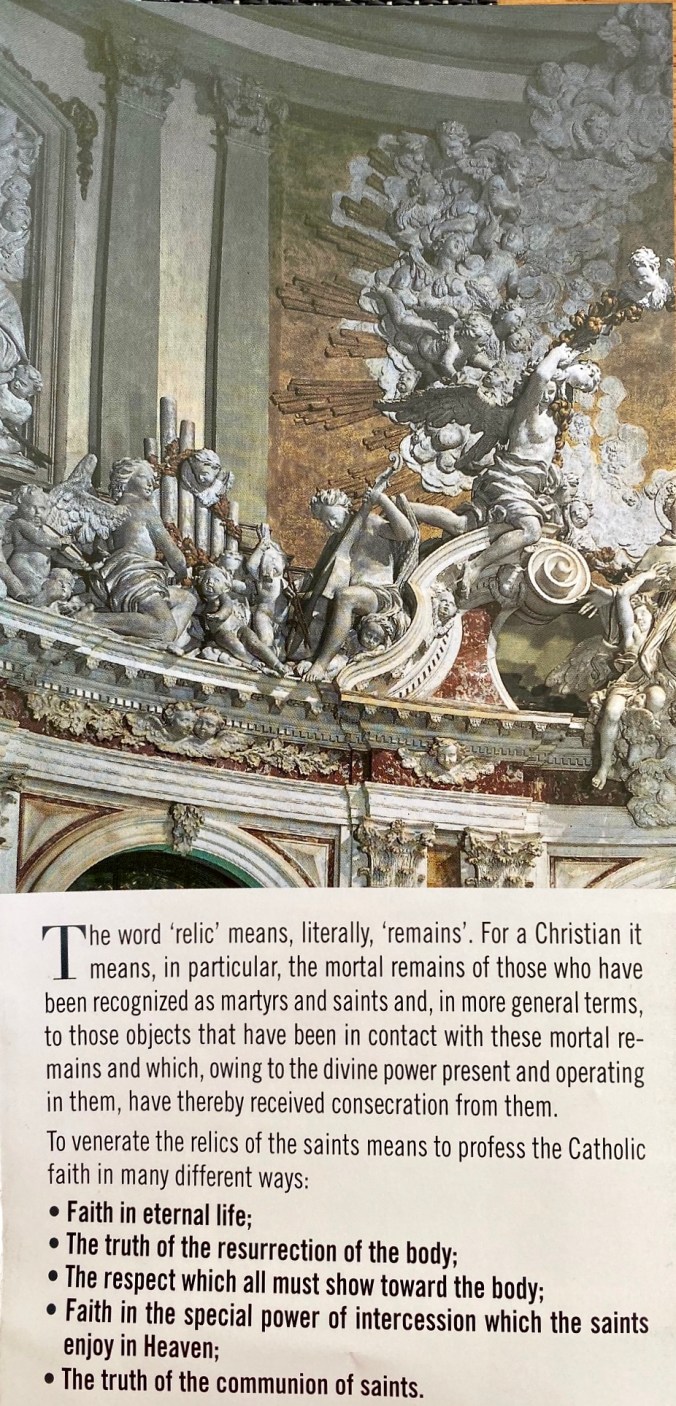

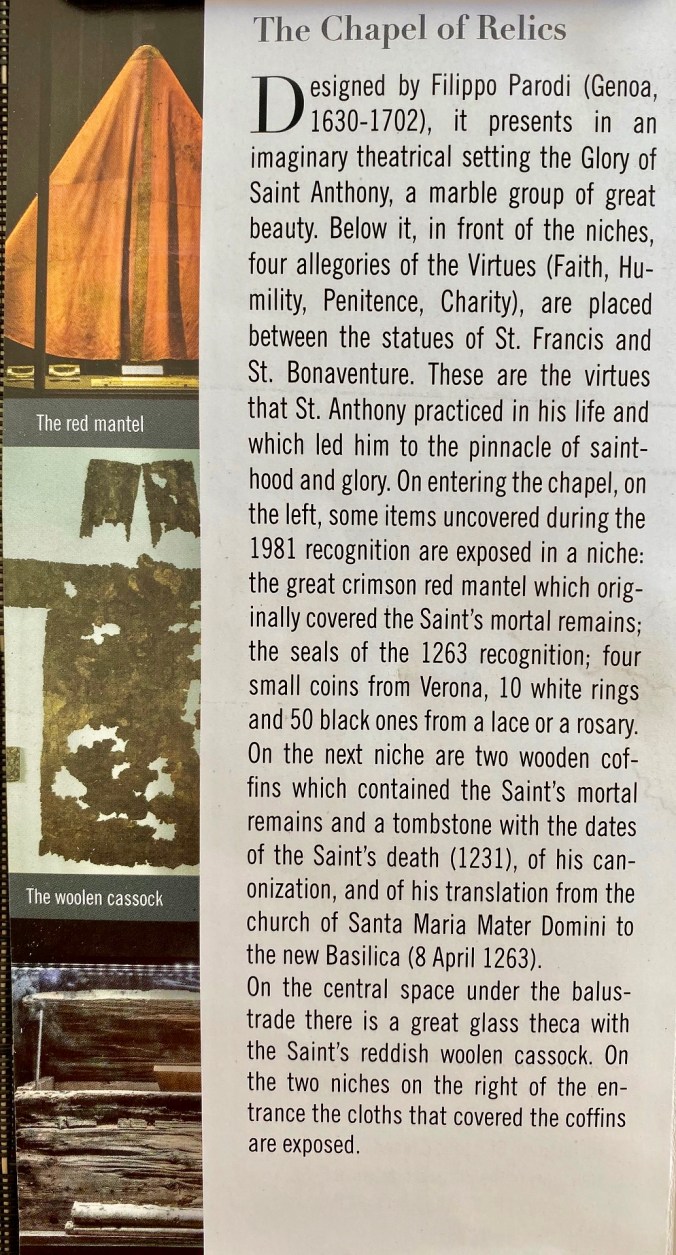

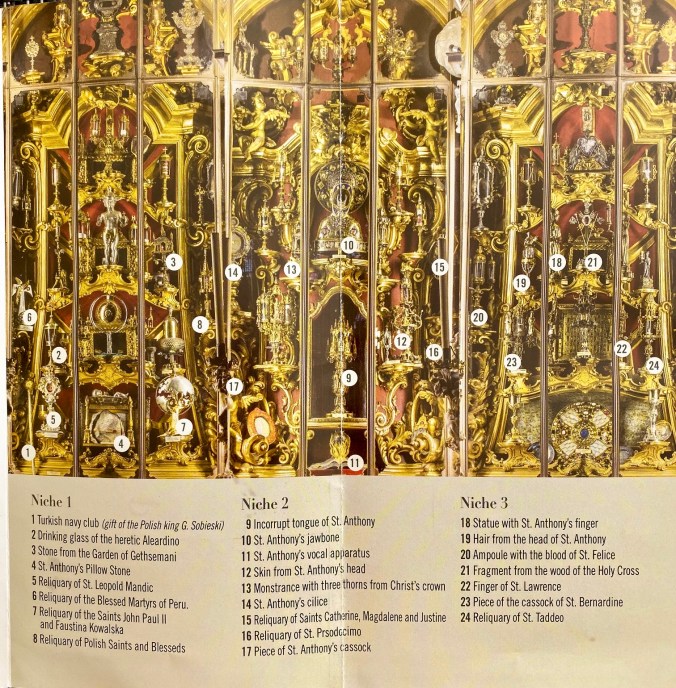

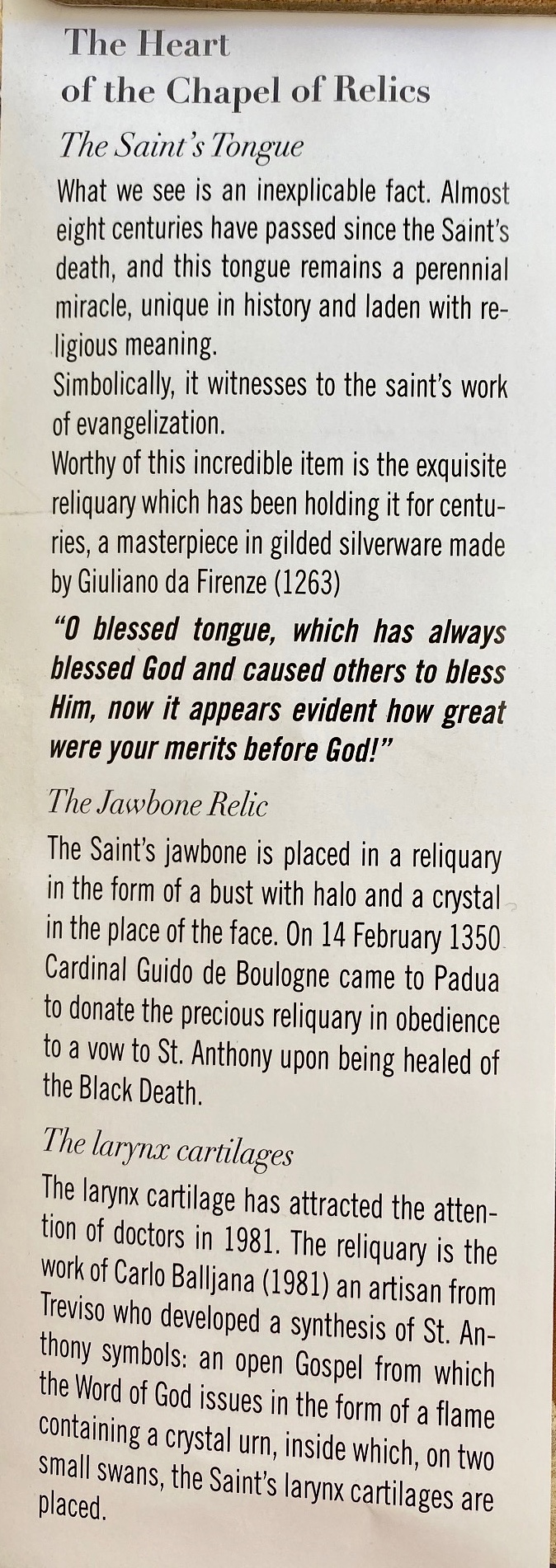

The Chapel of Relics, Saint Anthony’s Basilica, Padua

The brochure tells the story. I couldn’t make this stuff up!

Ponte Vecchio, Florence, all lit up

In early October, I had the good fortune to spend a lovely evening at La Società Canottieri on the banks of the Arno in Florence. The evening was spectacular enough, getting to visit this special place and watch afternoon fade into evening. I’ve posted about it here and here.

But, then, somebody somewhere flipped a switch the the Ponte Vecchio was illuminated in purple. We were all surprised and there were audible gasps of delight as we took in the bright lights on the old bridge.

La Società Canottieri, Firenze, Part 2

Recently I posted about my evening spent at La Società Canottieri, Firenze. It was a special evening and satisfied a long hoped for wish.

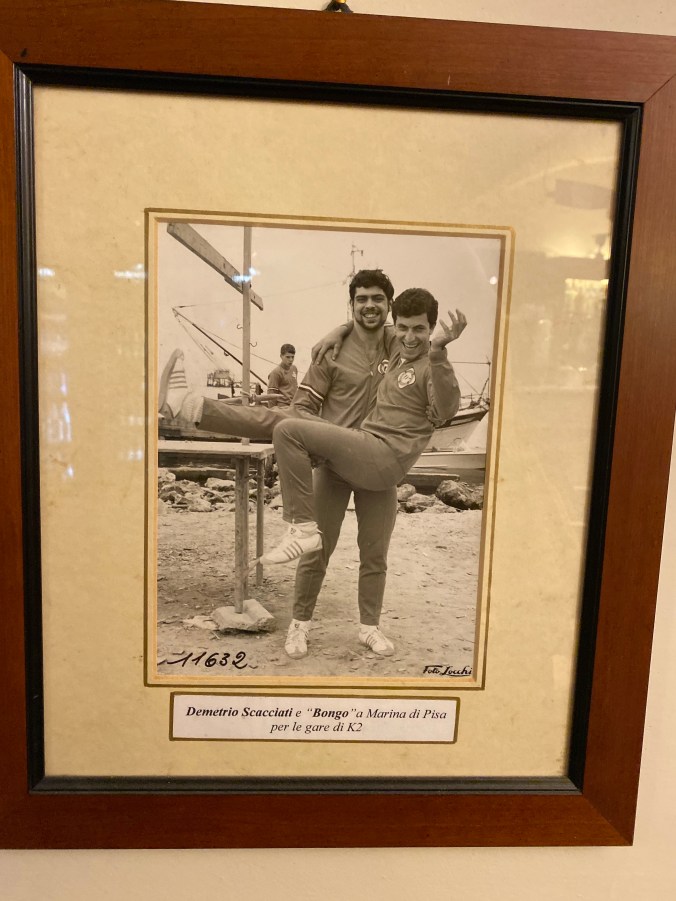

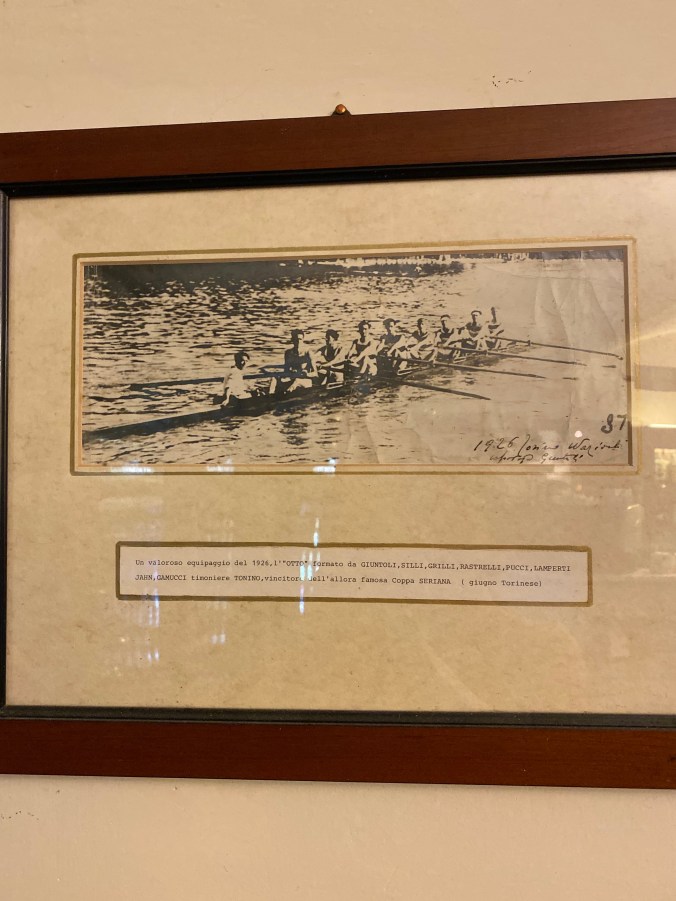

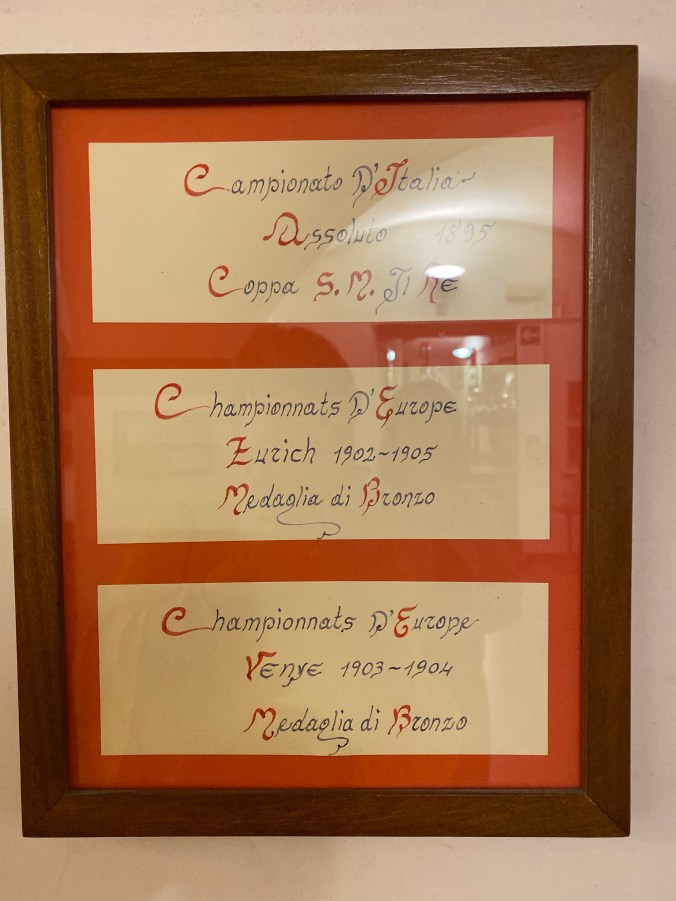

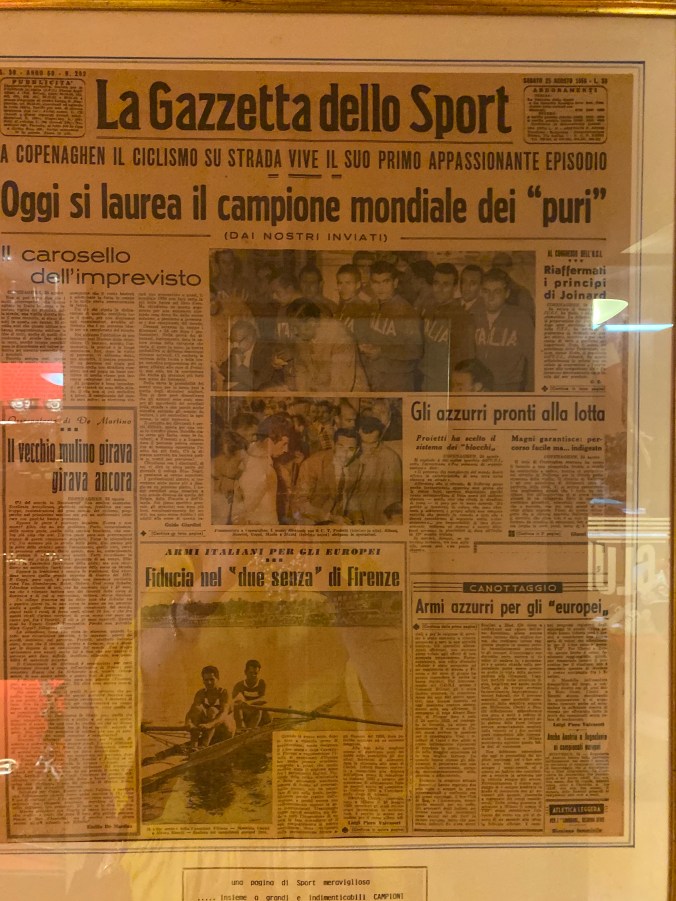

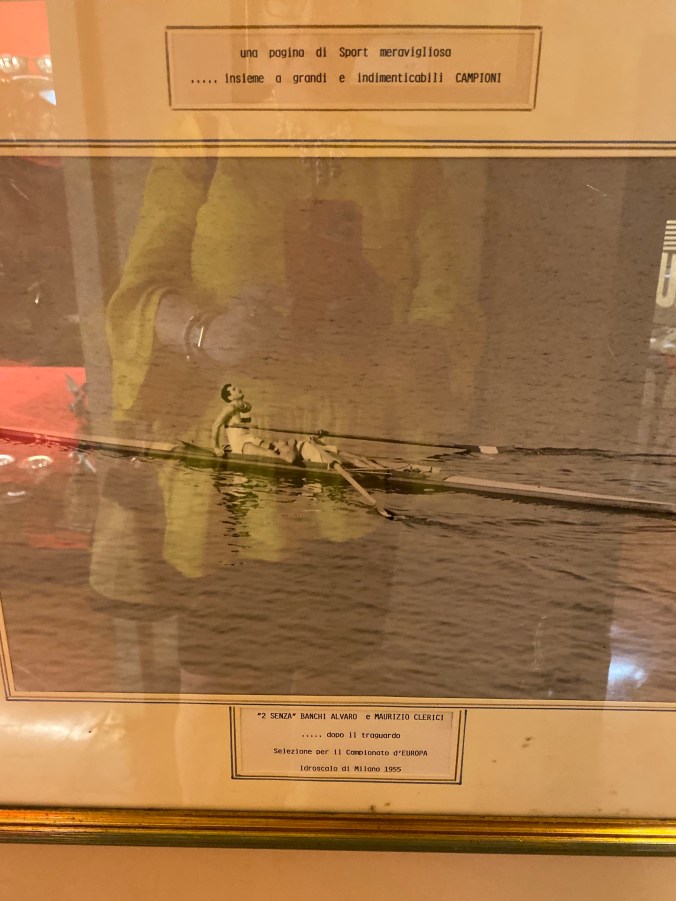

In this post I want to share some of the pictures I took that night, mostly of the club’s interior, with lots of fun memorabilia on display.

So, here we go with the memorabilia on display at the club:

For posterity, a marker in Florence

One of the millions of things I love about Italy is: they never miss an opportunity to mark something for posterity. No matter how modest the contribution.

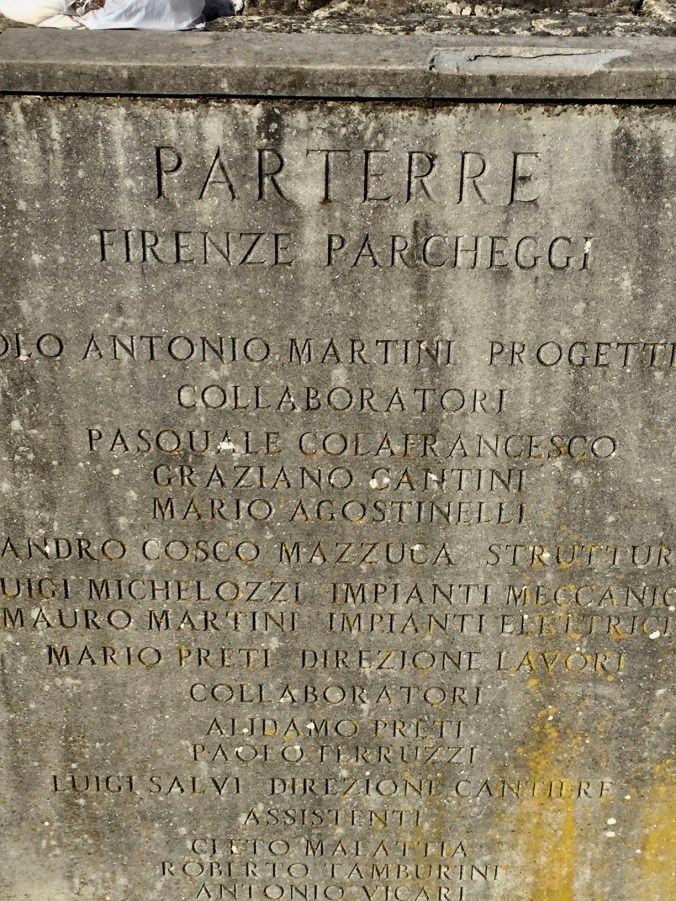

Case in point, a stone’s throw from my home on the north end of Florence is an underground parking lot in a neighborhood known as the “Parterre.” It serves a vital function of providing parking for some of the thousands of cars that cannot enter historic Florence on any given day, because the historic center is designated a pedestrian area and does not allow entry for unauthorized vehicles.

The above-ground section marking the Parterre is nothing much to brag about:

But, nevertheless, the city’s leaders wanted credit given to the masterminds behind the underground parking, and to this end they installed a very grand-sounding plaque with inscriptions lauding them all.

The birth of Coty perfumes; how an up-start Corsican invented a bran

One of the many visitors to the Paris exposition was twenty-five-year-old François Spoturno (known to history as the more gentrified François Coty), a native of Corsica who had come to Paris to make his fortune. A born charmer, he already had proved his skills as a salesman in Marseilles. Now, using a connection he had cultivated during his military service, he found a position as attaché to the senator and playwright Emmanuel Arène. It was a tremendous coup.

Spoturno was born on 3 May 1874 in Ajaccio, Corsica. He was a descendant of Isabelle Bonaparte, an aunt of Napoleon Bonaparte. His parents were Jean-Baptiste Spoturno and Marie-Adolphine-Françoise Coti, both descendants of Genoese settlers who founded Ajaccio in the 15th century. His parents died when he was a child and the young François was raised by his great-grandmother, Marie Josephe Spoturno, and. after her death, by his grandmother, Anna Maria Belone Spoturno. Grandmother and grandson lived in Marseille.

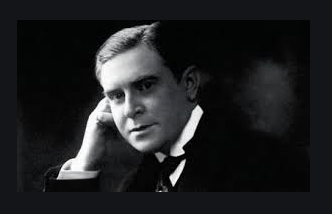

Coty and his wife.

Young Spoturno may not have had money, but he now had access to the glittering upper reaches of 1900 Paris, with its salons, clubs, and fashionable gatherings. As he quickly realized, it was a world in which women played a key role, from the most elegant aristocrats to the grandest courtesans—a fact of great importance, as it turned out, since women would soon make Spoturno’s fortune.

Spoturno’s interest was not in clothing but in perfume. At the opening of the new century, the perfect perfume was as essential to the well-dressed Parisian woman as was the latest fashion in dresses, and the French perfume industry was booming, with nearly three hundred manufacturers, twenty thousand employees, and a profitable domestic as well as export business.4 Naturally, perfume makers took the opportunity to display their wares at the 1900 Paris exposition, and Spoturno took the time to wander among their displays, including those of leading names such as Houbigant and Guerlain.

Spoturno was not yet sufficiently knowledgeable to judge a perfume’s quality, but he did note that the bottles containing these perfumes were old-fashioned and uninspired. It would not be long before it would occur to him that perhaps their contents were also a trifle outdated.

But first he had to find his way into the perfume business. After getting a job as a fashion accessories salesman and marrying a sophisticated young Parisian, Spoturno became acquainted with a pharmacist who, like other chemists at the time, made his own eau de cologne, which he sold in plain glass bottles. He also met Raymond Goery, a pharmacist who made and sold perfume at his Paris shop. Coty began to learn about perfumery from Goery and created his first fragrance, Cologne Coty.

One memorable evening, Spoturno sniffed a sample of his friend’s wares and turned up his nose. The friend then dared him to make something better, and Spoturno went to work.

He hadn’t the slightest idea of how to proceed, but in the end he managed so well that his friend had to admit that he was gifted. Yet natural gifts were not enough in the perfume business, and soon Spoturno decided to go to Grasse, the center of France’s perfume industry, to learn perfume-making from the experts. Along the way he would change his name to his mother’s maiden name. Only he would spell it “Coty.”

The brand’s first fragrance, La Rose Jacqueminot, was launched the same year and was packaged in a bottle designed by Baccarat.

L’Origan was launched in 1905; according to The Week, the perfume “started a sweeping trend throughout Paris” and was the first example of “a fine but affordable fragrance that would appeal both to the upper classes and to the less affluent, changing the way scents were sold forever.”

Following its early successes, Coty was able to open its first store in 1908 in Paris’ Place Vendôme. Soon after, Coty began collaborating with French glass designer René Lalique to create custom fragrance bottles, labels, and other packaging materials, launching a new trend in mass-produced fragrance packaging.

Coty also established a “Perfume City” in the suburbs of Paris during the early 1910s to handle administration and fragrance production; the site was an early business supporter of female employees and offered benefits including child care.

The year was 1904, and François Coty was about to engage in his own act of rebellion. Or was it simply a superb marketing tactic? We do not know. What we do know is that on one fateful day, on the ground floor of the Louvre department store, Coty smashed a bottle of perfume on the counter—with momentous results. Following his decision to learn more about the perfume business, Coty had indeed gone to Grasse, which was the long-established center for cultivating the flowers essential for making perfume. It was also the research center for the entire perfume industry. There, he applied for training at the esteemed Chiris company, which represented the cutting edge of current perfume technology. Fortunately, the head of the firm, now a senator, was a friend of Coty’s patron, Senator Arène, which eased Coty’s way. Coty then worked diligently for a year to learn all that he could, from flower cultivation to essential oils, spending much of his time in the laboratory. He analyzed, he synthesized, and he learned how to blend. During his apprenticeship, Coty learned about two new tools that the established perfumers had for the most part neglected in favor of more traditional methods. The first of these was the discovery of extraction by volatile solvents, a technique that made extraction of large quantities of fragrance possible and could even be used with nonfloral substances such as leaves, mosses, and resins. Shortly before the turn of the century, Louis Chiris secured a patent on this technique and set up the first workshop based on solvent extraction. Coty was an early student of this pioneering work.

The second and even more revolutionary discovery was that of synthetic fragrances. Earlier in the nineteenth century, French and German scientists had discovered synthetic fragrance molecules in organic compounds such as coal and petroleum that allowed perfumers to approximate scents that could not otherwise be easily extracted. It was an amazing breakthrough, and a few perfumers experimented briefly with the artificial scents of sweet grass, vanilla (from conifer sap), violet, heliotrope, and musk. A few also explored the possibilities of the first aldehydes, which gave perfumes a far greater strength than ever before. Yet with only a few exceptions, established perfumers in the early 1900s avoided these synthetic molecules. In studying the successful perfumes of the day, Coty

concluded that most were limited in range and old-fashioned, pandering to conservative tastes with heavy, overly complex floral scents that were almost interchangeable. He had educated his nose and learned his trade, and although he never would become a perfumer per se, he had an extraordinary imagination and a gift for using it to explore new realms. It was with this gift, newly honed, that he returned to Paris, and with ten thousand borrowed francs set up a makeshift laboratory in the small apartment where he and his wife lived. He was willing—even eager—to break with convention, aiming to create a perfume that combined subtlety with simplicity. Even at the beginning, his formulas were simple but brilliant, using synthetics to enhance natural scents. Coty also revolutionized the

bottles containing his perfumes. Remembering the beauty of the antique perfume bottles at the 1900 Paris exposition, which made the virtually standardized perfume bottles of the day look boring, Coty unhesitatingly went to the top and hired Baccarat to produce the lovely, slim bottle for La Rose Jacqueminot, his first perfume. As he later remarked, “A perfume needs to attract the eye as much as the nose.”16 Coty’s wife sewed and embroidered the silk pouches with velvet ribbons and satin trim that contained the bottles, and Coty now drew on his sales skills—this time selling his own rather than someone else’s product. Much to his dismay, it proved almost impossible to break through the established perfumers’ stranglehold on the market. Coty went from rejection to rejection, until one day he lost his composure. He was on the

ground floor of the Louvre department store trying to sell La Rose Jacqueminot, and the buyer was about to show him the door. In anger—or in what perhaps was a supreme act of showmanship—Coty smashed one of the beautiful Baccarat bottles on the counter, and a revolution began. According to legend, women shoppers smelled the perfume and flocked to the source, buying up Coty’s entire supply. The buyer took note, became suddenly cooperative, and Coty was on his way. After the fact, some groused that Coty had staged the entire stunt, including hiring actresses to play the part of shoppers entranced by his perfume. Yet by this time it didn’t matter. Coty had made his first publicity coup, whether or not it was intentional, and he and his perfumes were launched.

François Coty was also doing well in new quarters, which he had shrewdly taken in an affluent part of town, just north of the Champs-Elysées. Space there was limited, but the address (on Rue La Boétie) was a good one and worth the effort to cram showroom, shop, laboratory, and packaging department under one small roof. Much as Coty expected and desired, his perfume business continued to surge. The year 1905 was a big one for him, during which he presented two new hits: Ambre Antique and, especially, L’Origan, which according to perfume aficionados was an exceptionally daring blend, suitable for those daring Fauvist times. It was while Coty was launching his seductive new perfumes that an ambitious young woman by the name of Helena Rubinstein was studying dermatology

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

McAuliffe PhD, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Kindle Edition.

Charting my progress, for the record

How’s my goal of living in Italy working out? Pretty well. It hasn’t been easy or fast, but it has been steady.

I came to Florence at the end of November in 2016. I arrived with a student Visa, which let me live in Italy beyond the 90 days any American can stay in Europe as a tourist. I stayed in Florence for 11 months and successfully obtained the all important Permesso di Soggiorno with that Visa. The Permesso expired after 8 months, regardless of the fact that I had already paid for Italian language school for 12 months. Lesson 1: there is no logic.

I returned to the states in October of 2017, going from Florence to Chicago where it was necessary for me to go to the Italian Consulate to apply for an elective residency Visa. Such a Visa allows Americans like me, if we are fortunate enough to receive the Visa, to live in Italy under certain circumstances. Chicago was necessary for me because my home is in Denver and that’s the way that cookie is divided. I filed the myriad documents needed to show my eligibility for the elective residency Visa, and then went to Denver to wait its hoped-for arrival.

Fortunately, I received the Visa. But, it has certain conditions. I won’t enumerate them all, but one of the most important ones is that I am not allowed to have gainful employment in Italy. I cannot receive any payment from anyone in Italy. Doing so could result not only in my Visa being revoked, but the Italian government could prohibit me from ever setting foot in Italy again. It’s a powerful rule.

I returned to Florence in December of 2017, armed with my new elective residency Visa. The first step, then, once within the country, is that within 8 days, one must apply for the Permesso di Soggiorno. I applied for this before Christmas in 2017 and then began to wait for its arrival.

Some people will receive their Permesso within a month, or so they say. Others, like me, are not so lucky. I waited for 8 months to receive word that my new Permesso was ready for me to pick up at the police station, or the dreaded Questura.

In July of 2018, I received a text message telling me to appear at the Questura on a certain date in early August, at a certain time. I did as I was asked. I turned in my old, expired, student-based Permesso, and received my new one. Unfortunately, my new Permesso was already expired when I received it. You read that right. Welcome to Italy.

The true impact of this situation on my daily life was nil. As long as one re-applies for a new Permesso within a short period, and keeps the receipt of that application with them at all times, typically no problems will result. Fortunately, I have never been stopped by the police in Italy and asked to show my documents. Theoretically, even if the police did stop me and ask for my documents, the receipt of the new Permesso application would suffice.

I filed my new application for a new Permesso in late September of 2018. Of course I kept a copy of the receipt for fees paid for that application with me at all times.

And then I began the wait for my new Permesso.

So, what is the importance of this waiting period on my life? Again, on a daily basis it is unnoticeable. However, there are other steps that one needs to do to truly function in present day Italy after one receives the Permesso.

For example, I tried to open a bank account in Italy in the winter of 2017, while I had my student Visa and my related Permesso. With the assistance of an Italian friend, we could not find a bank that was willing to open an account for me. I suppose I was considered to be too transient to bother with.

At that time, I was warned about opening an Italian bank account in any case. Still not having one, I cannot tell you exactly why people recommended I NOT open an account, should I ever find a bank that was willing to let me. Why? As I understand it, bank accounts here are very different from what I’m used to in the USA. For starters, it is quite costly to maintain an account here. In any case, no bank would open an account for me if I didn’t have a current Permesso di Soggiorno. Although I never tried to open an account with just my receipt, perhaps I could have done so. It just didn’t seem worthwhile to try, so I didn’t. For months I expected to receive my new Permesso and then I would try. That was my plan

Once I received my elective residency Visa and had an actual, unexpired Permesso di Soggiorno, I could follow other steps. First among these is applying for a Certificato di Residenza. I still don’t understand why this is important to have, but it is. There are certain things I just accept here and just accept that it makes no sense to me. The Serenity Prayer comes in handy.

After obtaining the Certificato di Residenza, one can apply for the Carta d’ Identita, which is necessary to have before applying for an Italian health care card which would allow me to seek medical treatment in Italy should the need arise. Up until such time, it is incumbent upon me to maintain a private traveler’s health insurance policy to cover unforseen events. As a matter of fact, proof of such a policy is a necessary document needed to apply for both the elective residency Visa and also for the Permesso di Soggiorno.

So, I’ve been waiting since last September (2018), for my new Permesso di Soggiorno. Six months went by, 7 months, 8 months, 9 months, 10 months and then, finally, I received a text message telling me my new Permesso would be ready for me to pick up at the Questura last week. I went with baited breath, wondering if it would already be expired again.

This time, I got lucky. True, I had to wait 11.5 months for the thing, but at least I got one that does not expire for 12 months! I’m suddenly completely legal, not needing any receipts for anything, at least for a year! Then I get to do the whole thing over again.

So, how did I celebrate? I did so by immediately (the next week) applying for my Certificato di Residenza. I was informed by knowledgeable people and blogs that this would arrive 45 days after I applied for it. Then I could apply for the Carta d’ Identita.

Imagine my surprise, after going to the correct government office in Florence, when the clerk told me she could produce and give it to me that same day! She asked me if I wanted to apply for the Carta d’ Identita and I mostly certainly did. She gave me the forms to sign and submitted them. She said I should receive it within a week (I’ll expect it within a month, if I’m lucky).

Once I have that in hand, I intend to apply for the Italian health care card which, if I understand things correctly, will allow me to seek medical assistance if the need were to arise, which I obviously hope it will not!

And, bonus, in the meantime I met an Italian who works with a lot of English speakers, and she told me that she thought I could apply for a “bank account” with the Italian postal system. Say what?

It turned out, she was correct. I went into the Post Office in Florence last week and opened an account that seems to be something like a bank account…even if it is with the postal system. I have a new debit card and the ability to wire money into this account from the US. For the first time since I arrived in Italy in November of 2016, I will be able to pay my rent to my landlord’s bank account. Up until now, I’ve had to take cash out of the ATM over the period of a few days to get enough money together to pay my rent.

All of a sudden, I feel like I’m living in the 21st century again. However, I’ve been in Italy long enough to know that any number of things could and may still go wrong. I’ll check in again once money has successfully been wired from the states to my post office bank account and I’ve paid my rent. Fingers crossed.

And, next week, I’ll apply for a health insurance card. Step by slow step, my life in Italy is becoming complete.

Arrividerla, L

Florence’s tiny little wine windows

One of the hundreds of interesting things you see when walking around the city of Florence are these small windows, measuring about 12 inches wide by 15 inches tall, cut into the masonry of some major palazzi. There are hundreds of them in Florence.

The buchette del vino (“small holes [for] wine”) were added to the buildings by entrepreneurial families who produced wine on their country estates and thought to themselves, “why not sell some in Florence on a glass by glass, or a refilled bottle by bottle, basis?”

Together, these windows form a collection of Renaissance-era vestiges of a once-popular and admirably no-fuss form of wine sales.

Without exception, I have never seen one of these windows open. They are usually boarded up, sometimes in quite decorative ways.

But now, an organization is working to preserve—and help reopen—the city’s “wine windows.”

“These small architectural features are a very special commercial and social phenomenon unique to Florence and Tuscany,” Matteo Faglia, a founding member of the Associazione Culturale Buchette del Vino, told Unfiltered via email. “Although they are a minor cultural patrimony, nevertheless, they are an integral part of the richest area of the world in terms of works of art and monuments—Tuscany.”

The buchette first came into vogue in the 16th century, when wealthy Florentines began to expand into landowning—notably, owning vineyards—in the Tuscan countryside. The aristocrats’ new zeal for selling wine was matched only by that for avoiding paying taxes on selling wine, so they devised the simplest model for wine retail they could: on-demand, to-go, literally hand-sold through a hole in the wall of their residences.

It was convenient for drinkers, too: Knock on the window with your empty bottle, and the server, a cantiniere, would answer; upon receiving the bottle and payment, he would return with a full bottle of wine. Buchette eventually became popular enough that nearly every Florentine family with vineyards and a palace in Florence had a wine window, and soon the trend spread to nearby Tuscan towns like Siena and Pisa.

The windows stayed open for the next three centuries, but by the beginning of the 20th century, more social wine tavernas had spread throughout the city, with better-quality wine, better company and equally easy access to a flask.

By 2015, most Florentines had lost track of their wine windows, if not vandalized them. That year, the Associazione was founded, with a mission to identify, map and preserve the buchette—nearly 300 catalogued so far.

And this summer provided a new boost to their work: One restaurant has cracked open its buchetta anew for business. Babae is the first restaurant to re-embrace the old tradition, filling glasses for passersby through their buchetta for a few hours each evening.

It’s a welcome development to the lovers of wine windows. “Although the ways of selling wine have obviously changed since the wine windows were fully active … this small gesture, which highlights a niche of Florentine history, is very welcome,” said Faglia, “to help to keep alive this antique and unique way of selling one of Tuscany’s most important agricultural and commercial products: its wine.”

This new association even has a Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/buchettedelvino/

The wonders of Padua (Padua, part 3)

Padova or Padua is a big subject! I’ve recently posted 2 times about it, here, here, here and here. And, still, I am far from done!

This post includes a list of the major features that grace this lovely, historic town. But first, a sweet little video about the town itself:

Undoubtedly the most notable things about Padova is the Giotto masterpiece of fresco painting in the The Scrovegni Chapel (Cappella degli Scrovegni). This incredible cycle of frescoes was completed in 1305 by Giotto.

It was commissioned by Enrico degli Scrovegni, a wealthy banker, as a private chapel once attached to his family’s palazzo. It is also called the “Arena Chapel” because it stands on the site of a Roman-era arena.

The fresco cycle details the life of the Virgin Mary and has been acknowledged by many to be one of the most important fresco cycles in the world for its role in the development of European painting. It is a miracle that the chapel survived through the centuries and especially the bombardment of the city at the end of WWII. But for a few hundred yards, the chapel could have been destroyed like its neighbor, the Church of the Eremitani.

The Palazzo della Ragione, with its great hall on the upper floor, is reputed to have the largest roof unsupported by columns in Europe; the hall is nearly rectangular, its length 267.39 ft, its breadth 88.58 ft, and its height 78.74 ft; the walls are covered with allegorical frescoes. The building stands upon arches, and the upper story is surrounded by an open loggia, not unlike that which surrounds the basilica of Vicenza.

The Palazzo was begun in 1172 and finished in 1219. In 1306, Fra Giovanni, an Augustinian friar, covered the whole with one roof. Originally there were three roofs, spanning the three chambers into which the hall was at first divided; the internal partition walls remained till the fire of 1420, when the Venetian architects who undertook the restoration removed them, throwing all three spaces into one and forming the present great hall, the Salone. The new space was refrescoed by Nicolo’ Miretto and Stefano da Ferrara, working from 1425 to 1440. Beneath the great hall, there is a centuries-old market.

In the Piazza dei Signori is the loggia called the Gran Guardia, (1493–1526), and close by is the Palazzo del Capitaniato, the residence of the Venetian governors, with its great door, the work of Giovanni Maria Falconetto, the Veronese architect-sculptor who introduced Renaissance architecture to Padua and who completed the door in 1532.

Falconetto was also the architect of Alvise Cornaro’s garden loggia, (Loggia Cornaro), the first fully Renaissance building in Padua.

Nearby stands the il duomo, remodeled in 1552 after a design of Michelangelo. It contains works by Nicolò Semitecolo, Francesco Bassano and Giorgio Schiavone.

The nearby Baptistry, consecrated in 1281, houses the most important frescoes cycle by Giusto de’ Menabuoi.

The Basilica of St. Giustina, faces the great piazza of Prato della Valle.

The Teatro Verdi is host to performances of operas, musicals, plays, ballets, and concerts.

The most celebrated of the Paduan churches is the Basilica di Sant’Antonio da Padova. The bones of the saint rest in a chapel richly ornamented with carved marble, the work of various artists, among them Sansovino and Falconetto.

The basilica was begun around the year 1230 and completed in the following century. Tradition says that the building was designed by Nicola Pisano. It is covered by seven cupolas, two of them pyramidal.

Donatello’s equestrian statue of the Venetian general Gattamelata (Erasmo da Narni) can be found on the piazza in front of the Basilica di Sant’Antonio da Padova. It was cast in 1453, and was the first full-size equestrian bronze cast since antiquity. It was inspired by the Marcus Aurelius equestrian sculpture at the Capitoline Hill in Rome.

Not far from the Gattamelata are the St. George Oratory (13th century), with frescoes by Altichiero, and the Scuola di S. Antonio (16th century), with frescoes by Tiziano (Titian).

One of the best known symbols of Padua is the Prato della Valle, a large elliptical square, one of the biggest in Europe. In the center is a wide garden surrounded by a moat, which is lined by 78 statues portraying illustrious citizens. It was created by Andrea Memmo in the late 18th century.

Memmo once resided in the monumental 15th-century Palazzo Angeli, which now houses the Museum of Precinema.

The Abbey of Santa Giustina and adjacent Basilica. In the 5th century, this became one of the most important monasteries in the area, until it was suppressed by Napoleon in 1810. In 1919 it was reopened.

The tombs of several saints are housed in the interior, including those of Justine, St. Prosdocimus, St. Maximus, St. Urius, St. Felicita, St. Julianus, as well as relics of the Apostle St. Matthias and the Evangelist St. Luke.

The abbey is also home to some important art, including the Martyrdom of St. Justine by Paolo Veronese. The complex was founded in the 5th century on the tomb of the namesake saint, Justine of Padua.

The Church of the Eremitani is an Augustinian church of the 13th century, containing the tombs of Jacopo (1324) and Ubertinello (1345) da Carrara, lords of Padua, and the chapel of SS James and Christopher, formerly illustrated by Mantegna’s frescoes. The frescoes were all but destroyed bombs dropped by the Allies in WWII, because it was next to the Nazi headquarters.

The old monastery of the church now houses the Musei Civici di Padova (town archeological and art museum).

Santa Sofia is probably Padova’s most ancient church. The crypt was begun in the late 10th century by Venetian craftsmen. It has a basilica plan with Romanesque-Gothic interior and Byzantine elements. The apse was built in the 12th century. The edifice appears to be tilting slightly due to the soft terrain.

Botanical Garden (Orto Botanico)

The church of San Gaetano (1574–1586) was designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi, on an unusual octagonal plan. The interior, decorated with polychrome marbles, houses a Madonna and Child by Andrea Briosco, in Nanto stone.

The 16th-century Baroque Padua Synagogue

At the center of the historical city, the buildings of Palazzo del Bò, the center of the University.

The City Hall, called Palazzo Moroni, the wall of which is covered by the names of the Paduan dead in the different wars of Italy and which is attached to the Palazzo della Ragione

The Caffé Pedrocchi, built in 1831 by architect Giuseppe Jappelli in neoclassical style with Egyptian influence. This café has been open for almost two centuries. It hosts the Risorgimento museum, and the near building of the Pedrocchino (“little Pedrocchi”) in neogothic style.

There is also the Castello. Its main tower was transformed between 1767 and 1777 into an astronomical observatory known as Specola. However the other buildings were used as prisons during the 19th and 20th centuries. They are now being restored.

The Ponte San Lorenzo, a Roman bridge largely underground, along with the ancient Ponte Molino, Ponte Altinate, Ponte Corvo and Ponte S. Matteo.

There are many noble ville near Padova. These include:

Villa Molin, in the Mandria fraction, designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1597.

Villa Mandriola (17th century), at Albignasego

Villa Pacchierotti-Trieste (17th century), at Limena

Villa Cittadella-Vigodarzere (19th century), at Saonara

Villa Selvatico da Porto (15th–18th century), at Vigonza

Villa Loredan, at Sant’Urbano

Villa Contarini, at Piazzola sul Brenta, built in 1546 by Palladio and enlarged in the following centuries, is the most important

Padua has long been acclaimed for its university, founded in 1222. Under the rule of Venice the university was governed by a board of three patricians, called the Riformatori dello Studio di Padova. The list of notable professors and alumni is long, containing, among others, the names of Bembo, Sperone Speroni, the anatomist Vesalius, Copernicus, Fallopius, Fabrizio d’Acquapendente, Galileo Galilei, William Harvey, Pietro Pomponazzi, Reginald, later Cardinal Pole, Scaliger, Tasso and Jan Zamoyski.

It is also where, in 1678, Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopia became the first woman in the world to graduate from university.

The university hosts the oldest anatomy theatre, built in 1594.

The university also hosts the oldest botanical garden (1545) in the world. The botanical garden Orto Botanico di Padova was founded as the garden of curative herbs attached to the University’s faculty of medicine. It still contains an important collection of rare plants.

The place of Padua in the history of art is nearly as important as its place in the history of learning. The presence of the university attracted many distinguished artists, such as Giotto, Fra Filippo Lippi and Donatello; and for native art there was the school of Francesco Squarcione, whence issued Mantegna.

Padua is also the birthplace of the celebrated architect Andrea Palladio, whose 16th-century villas (country-houses) in the area of Padua, Venice, Vicenza and Treviso are among the most notable of Italy and they were often copied during the 18th and 19th centuries; and of Giovanni Battista Belzoni, adventurer, engineer and egyptologist.

The sculptor Antonio Canova produced his first work in Padua, one of which is among the statues of Prato della Valle (presently a copy is displayed in the open air, while the original is in the Musei Civici).

The Antonianum is settled among Prato della Valle, the Basilica of Saint Anthony and the Botanic Garden. It was built in 1897 by the Jesuit fathers and kept alive until 2002. During WWII, under the leadership of P. Messori Roncaglia SJ, it became the center of the resistance movement against the Nazis. Indeed, it briefly survived P. Messori’s death and was sold by the Jesuits in 2004.

Paolo De Poli, painter and enamellist, author of decorative panels and design objects, 15 times invited to the Venice Biennale was born in Padua. The electronic musician Tying Tiffany was also born in Padua.

You must be logged in to post a comment.