Two current exhibitions celebrate this American master.

Two current exhibitions celebrate this American master.

Dale Chihuly shows up everywhere! He is a worldwide phenom…

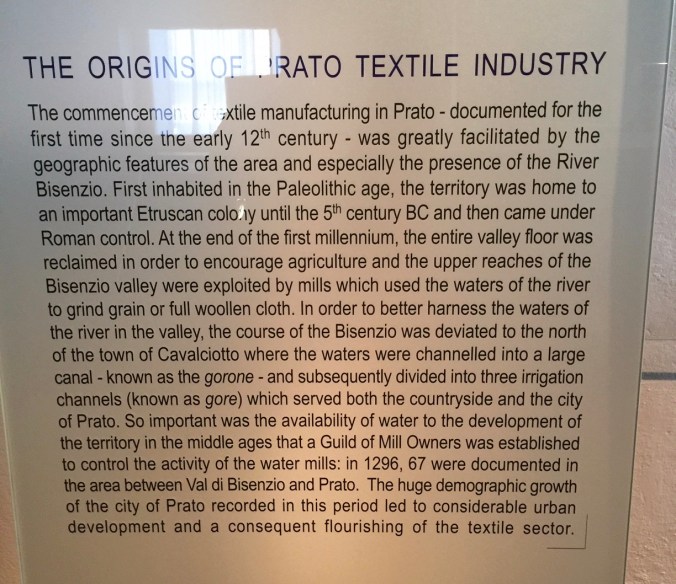

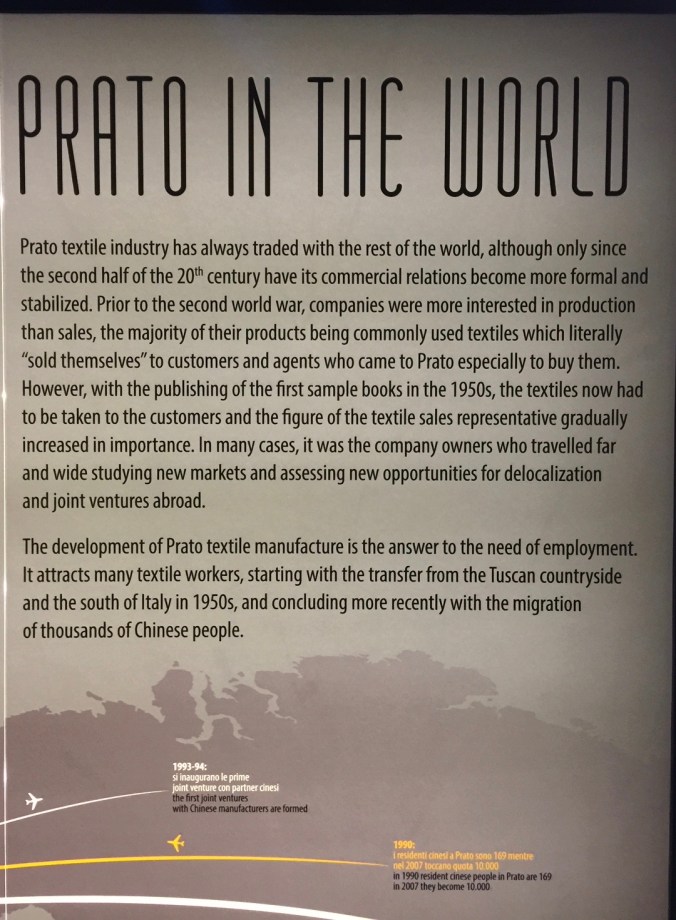

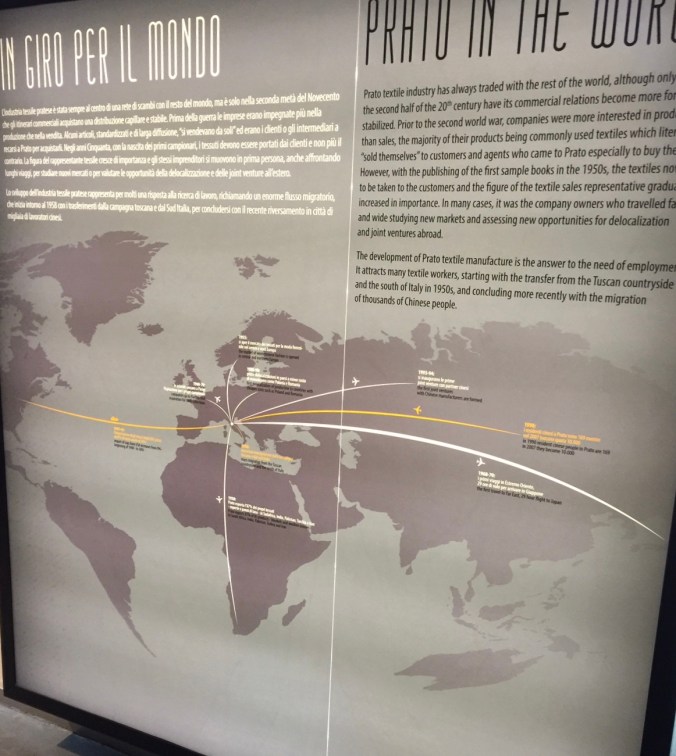

Prato, just a short distance from Florence, has a long and celebrated history of textile manufacture.

In honor of this long local tradition, Prato is also home to a fine textile museum, the Museo del Tessuto, dedicated to the city’s historical and contemporary textile production and art.

Even today, Prato is one of the largest industrial districts in Italy, the largest textile center in Europe and one of the most important centers in the world for the production of woolen yarns and fabrics.

The Museo is the largest cultural center of its kind in Italy. It celebrates the Prato district, which has been identified with textile production since the Middle Ages. Today the district boasts over 7,000 companies operating in this sector.

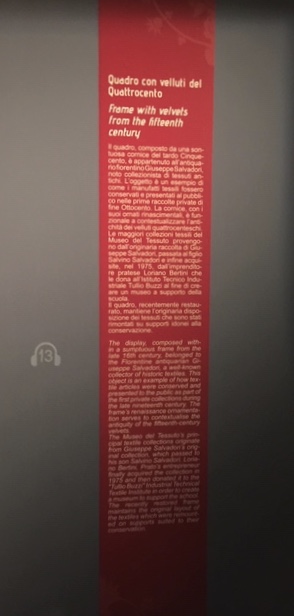

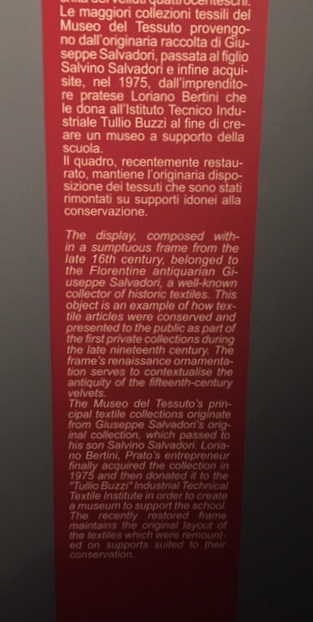

The Museum was founded in 1975 within the “Tullio Buzzi” Industrial Technical Textile Institute, as the result of an initial donation of approximately 600 historical textile fragments.

These were added to examples which had been gathered over the years by the Institute’s professors for students to consult and study. Since then, the collection has grown thanks to the contribution of the Buzzi Institute Alumni Association and other important civic institutions, such as the Municipality of Prato, Cariprato and the Pratese Industrial Union.

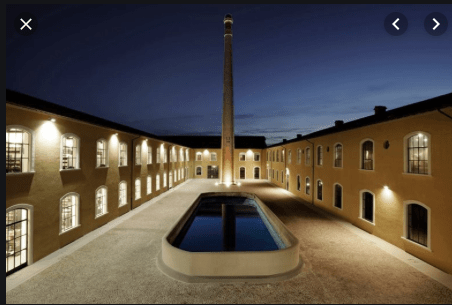

In 2003, the new, permanent home of the museum was inaugurated in the restored spaces of the former Campolmi factory, a precious jewel of industrial archaeology situated within Prato’s old city walls.

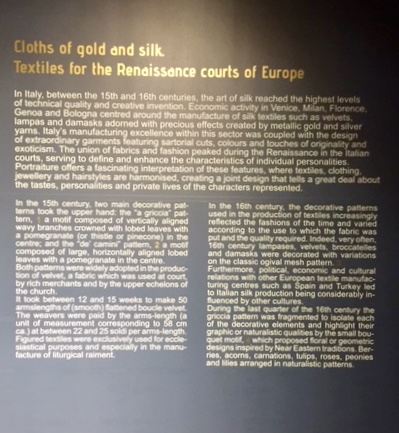

Prato began to specialize in textiles in the 12th century, when garment manufacturing was regulated by the Wool Merchants’ Guild.

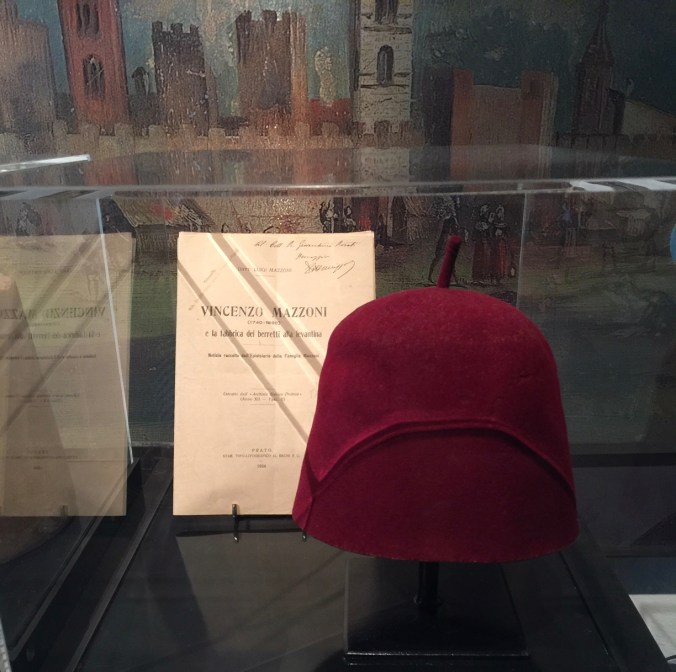

The political and economic decline experienced in Italy during the 16th and 17th centuries caused a drop in textile activities, but it resumed in the late 18th century with the production of knitted caps made for Arabian markets.

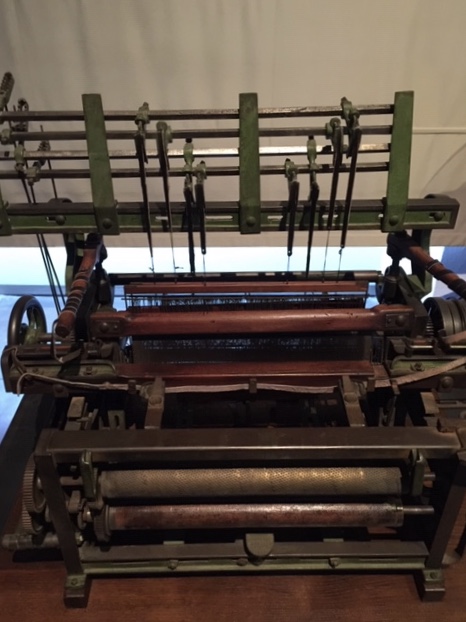

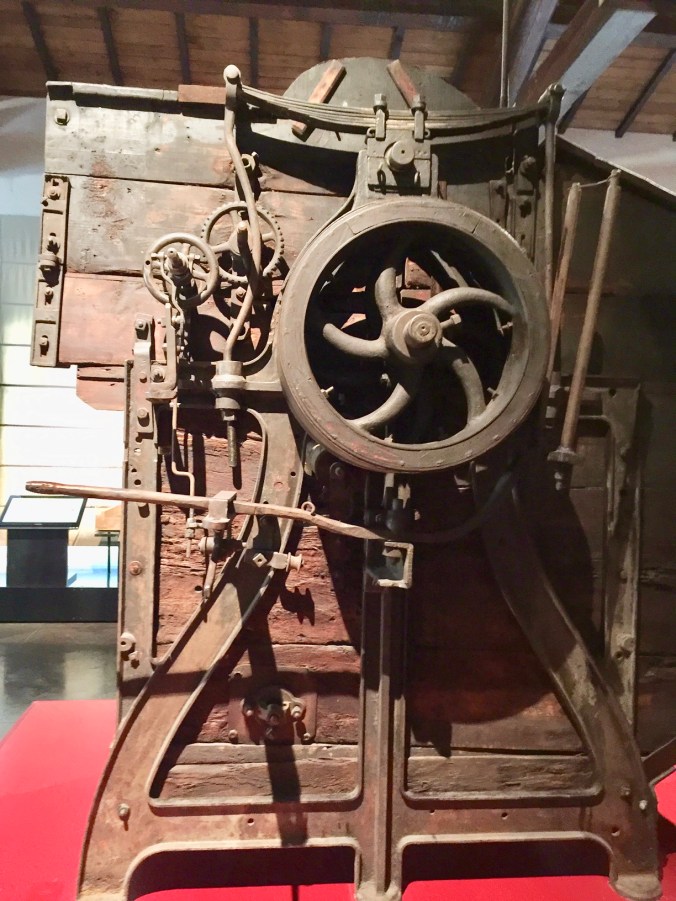

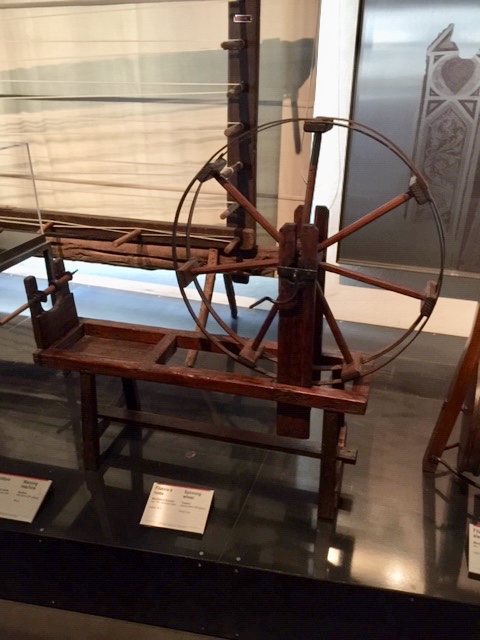

In the Prato area, industrial activities got under way at the end of the 19th century, with the introduction of mechanization (to which the brilliant local inventor Giovan Battista Mazzoni made important contributions) and with the intensification of textile working processes. The industrial take-off was also supported by foreign investors such as the Koessler and Mayer families of Austria, who created a company that lasted for decades and became locally known as the fabbricone, the big factory.

The lower costs of carded wool processing, caused by the gradually increasing production of recovered wool obtained from shredding old clothes and industrial scraps (“combings”).

Basically, up to World War II the Prato textile industry was divided in two production circuits: one based on large vertically integrated companies with generally low-level standard productions (rugs, military blankets, etc.) made for export to the poorer markets (Africa, India, etc.); the other based on groups of firms carrying out subcontract work for the production of articles designed for the clothing markets.

Between the postwar period and the early 1950s, the outlets towards low-level standard production markets rapidly disappeared. The production system underwent a rapid evolution, and the result was not so much the decentralization of subcontract work but an original form of reorganization largely based on the widespread distribution of work among small-scale enterprises (the so-called “industrial district”). The two dynamic factors of the new system were: (a) the subcontracting firms, which carried out the actual production and (b) the front-end firms, which were involved in product design.

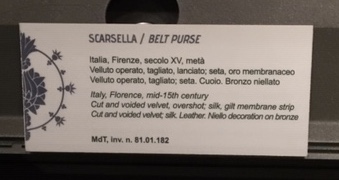

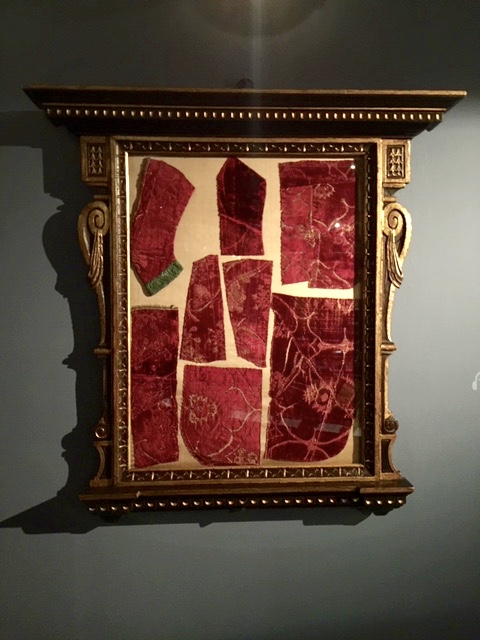

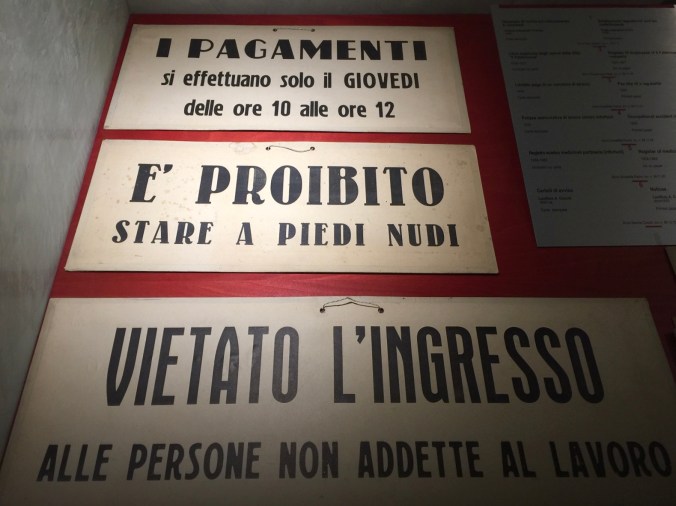

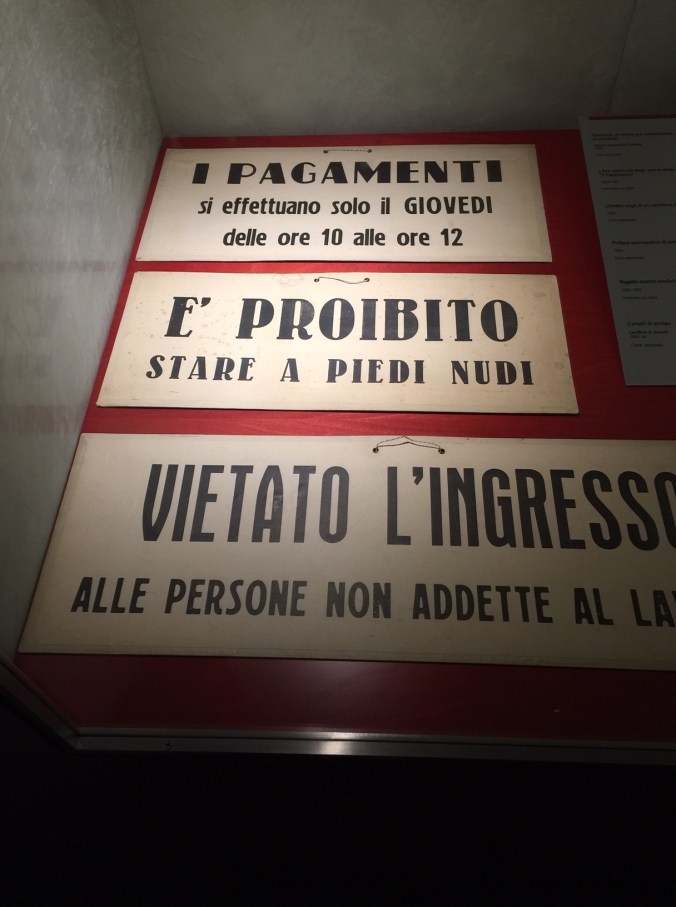

Below, some miscellaneous shots of the museum.

The “Emporio Duilio 48,” was founded in Florence (in the current Coin department store building, in Via de ‘Calzaiuoli) in 1902. The sales formula was, everything was under the price of 48 cents.

It is a fascinating story about early 20th-century Florence, with the tragedy of WWII a part of it.

The creator of the formula “all at 48 cents” was Joseph (Giuseppe) Siebzehner who was born in Vienna in 1863 and died in the Milan-Auschwitz route in the train departed on 29 January 1944 from platform 21). He was a Jewish merchant of a large Polish family, originally from Kańczuga (south-eastern Poland), married to Amalia Koretz (born in Plzeň on 15 March 1871 and dead in Auschwitz), daughter of Ferdinando.

The Siebzehner, already active in trade in Vienna at the end of 1800, took over the commercial activity called Grande Emporio Duilio and founded in Florence in 1888 by the Papalini brothers, who in turn had taken over the renowned Bazar Bonajuti, founded in 1834 by the architect (son of merchant) Telemaco Bonajuti.

The expansion of the Florentine headquarters in 1907 gave rise to the new name Emporio Duilio 48. This was soon joined by the two more stores in Montecatini and Viareggio; the latter was initially located in a bench where today stands the renowned shoe store Gabrielli, next to Magazzini 48.

It seems that after 1911 there were also 2 stores in Bologna, named simply: Emporio Duilio.

It’s clear that Giuseppe Siebzehner was a cutting-edge merchant, ahead of his time in Italy.

In fact, from the family archive (owned today by Count Federico di Valvasone and the last descendant, Riccardo Francalancia Vivanti Siebzehner), it emerges that Giuseppe already had two exclusive contracts at the end of the 19th century.

One with a comasco producer of festoons, lights of paper and decorations for the holidays.

The other, even more important, was with the great Bolognese blacksmith, Giordani, who built prams, tricycles, and especially bicycles for which he became a famous producer after WWI.

Even more avant-garde, Joseph was the first to produce a product catalog with mail order, a forerunner of today’s online shopping phenomenon.

The activity later passed into the hands of Giuseppe’s sons: Giorgio Vivanti Siebzehner (born in Florence, 1895 and died in Florence, 1952), lawyer and author of the Dictionary of the Divine Comedy and his brother Federico (born in Florence, 1900 and died in Florence in 1978), an electronic engineer who was among the first in Italy to conduct extensive experiments on ceramic resistance at the Italian Ceramics Society – Verbano. He, was awarded the honor of Knight to Merit of the Italian Republic in 1956.

Over time, the Francalancia Vivanti Siebzehner heirs of Valvasone and Bemporad took over the property until the commercial activity was sold to Coin Department store in 1988. The Viareggino building was instead ceded to the Fontana family in the 1990s. They later opened the Liberty Store, one of the most famous record and video games stores in the city.

When I grow up, I want to attend trapeze school in London. I saw this on my recent visit and I want to try it!

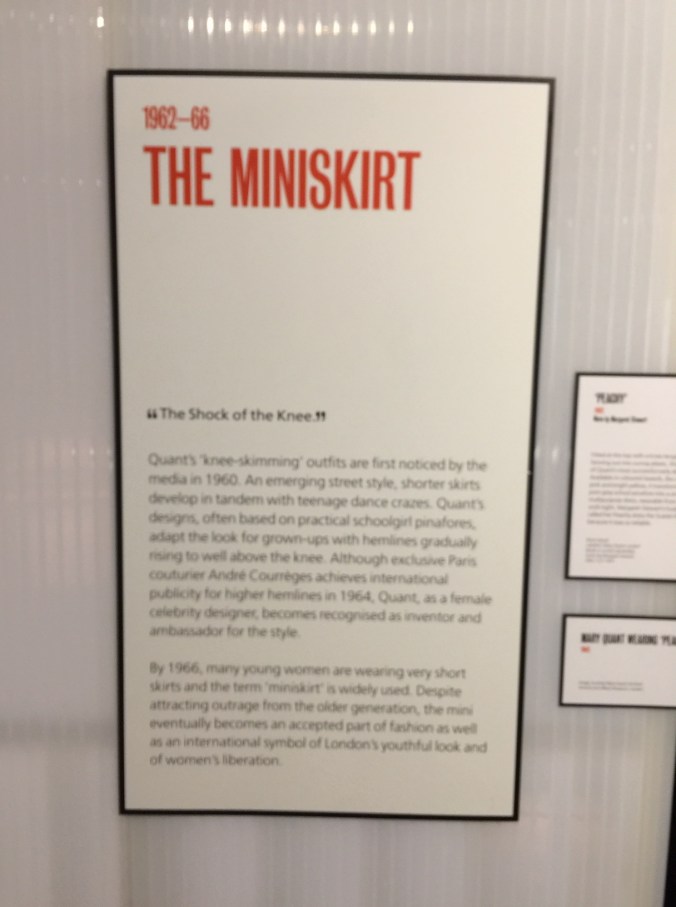

Last month I got to see the Mary Quant exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It was a childhood dream to wear Mary Quant fashion. Her work was not for sale in the small interior West American town where I grew up. But, my mother could sew anything and she fashioned some Quant designs for me. It breaks my heart that we didn’t keep all of those great things my mom sewed. But, they are stored in my memory and I remember how I felt when I wore them. That suffices in a pretty big way. Thanks mom!

But Mary Quant’s fashions, along with Twiggy and the Beatles, were a big part of my burgeoning (teenage) identity. Well, I mean that’s obvious. The name of my blog is from the Beatles: “Get back!”

The photo above of legs and the next 3 of hair were the kind of thing that fired my imagination. I couldn’t buy her fashions in South Dakota in the 1960s, but I could wear the tights and haircuts she inspired! And I did!

The rest of my pictures of the V & A exhibition are in no particular order. It was a great and very fun show, and I loved seeing and snapping pix of it.

The next photo was completely my scene. I wore these styles, these colors, and this vibe.

I didn’t know about Mary Quant’s paper dolls, or sticker books, or I would have been seeking them out. We didn’t have the internet back then, but I bet I could have figured it out, long-hand, so to speak. I guarantee you that I would have placed an international order with my babysitting money and waited for months to receive my treasures. This is how I honed my long game, which I still use with great results.

The jersey dress changed fashion. I’m a big fan and I still wear it.

A fixture in the London shopping scene, Liberty is a department store in Great Marlborough Street, in the West End of London. It sells highly curated selections of women’s, men’s and children’s clothing, make-up and perfume, jewelry, accessories, furniture and furnishings, stationery and gifts. The firm is well known for its floral and graphic prints.

I love any business with a great history and didactic information in a store window. They could just as well be showing their product line for sale, but they choose to edify. That’s my kinda store. Especially when it’s Liberty of London!

While the exterior of this classic London stop has remained in its mock Tudor style best, the interior and the product lines have changed vastly, even in my lifetime. While I prefer the way the store was when I first visited it with my mother in the 1980s, I have no doubt the management knows how to keep the store vital. I always enjoy a visit to this lovely emporium on any trip to London.

Before this summer, the last time I was at Liberty was in the early 2000s with my then 11-year-old red-headed son. At that time, Paula Pryke had a flower shop at the Liberty main entrance. It was dynamic! Her shop is gone and the store still has a ghost of a flower shop at its front door. But, I miss seeing Paula Pryke’s gorgeous arrangements there. He was less interested in Liberty than in going in and out of tube stations and traveling by train.

Liberty was created by Arthur Lasenby Liberty, who was born in Chesham, Buckinghamshire, in 1843. His father was a draper and, beginning work at 16, he was apprenticed to a draper. Later, Liberty took a job at Farmer and Rogers, a women’s fashions specialist in Regent Street, rising quickly up the ranks.

He was employed by Messrs Farmer and Rogers in 1862, the year of the International Exhibition. By 1874, inspired by his 10 years of service, he decided to start a business of his own, which he did the next year.

With a £2,000 loan from his future father-in-law, Liberty took the lease of half a shop at 218a Regent Street with three staff members. His shop opened in 1875 selling ornaments, fabric and objets d’art from Japan and the East.

Liberty hadn’t wanted to open just another store — he dreamed of an “Eastern Bazaar” in London that could fundamentally change homeware and fashion. Naming his new shop “East India House,” his collection of ornaments, fabrics and objects d’art from the Far East captured the attention of London, already in the crux of orientalist fervor.

It only took 18 months for Liberty to repay his loan, purchase the second half of the store, and begin to add neighbouring properties to his portfolio. From the beginning, the store also imported antiques, with the original V&A museum actually purchasing pieces of Eastern embroidery and rugs for its collection. As the business grew, neighboring properties were bought and added.

In 1884, he introduced the costume department, directed by Edward William Godwin (1833–86), a distinguished architect and a founding member of The Costume Society. Godwin and Liberty created in-house apparel to challenge the fashions of Paris.

In 1885, 142–144 Regent Street was acquired and housed the ever-increasing demand for carpets and furniture. The basement was named the Eastern Bazaar, and it was the vending place for what was described as “decorative furnishing objects”.

Liberty renamed the property “Chesham House,” after the place in which he grew up. The store became the most fashionable place to shop in London, and Liberty fabrics were used for both clothing and furnishings. Some of its clientele included famous Pre-Raphaelite artists.

To show the kind of innovative approach Liberty had for his business, in November of 1885, he brought 42 villagers from India to stage a living village of Indian artisans.

Liberty’s specialised in Oriental goods, in particular imported Indian silks, and the aim of the display was to generate both publicity and sales for the store.

During the 1890s, Liberty built strong relationships with many English designers. Some of these designers, including Archibald Knox, practiced the artistic styles we now call Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau. Liberty helped develop Art Nouveau in England through his encouragement of such designers. The company became associated with this new style, to the extent that even today in Italy, Art Nouveau became known as the Stile Liberty, after the London shop.

In 1882, author and playwright Oscar Wilde went on a tour of the United States, bringing with him a wardrobe full of clothes from Liberty, creating a demand for the store’s fashions with Americans. Wilde was obviously a huge fan of Liberty.

The iconic Tudor revival building was built by Liberty so that business could continue while renovations were being completed on the other premises. This great building was constructed in 1924 from the timbers of two ships: HMS Impregnable (formerly HMS Howe) and HMS Hindustan.

HMS Impregnable (c.1900), one of the two ships used to build Liberty

The emporium was designed by Edwin Thomas Hall and his son, Edwin Stanley Hall. They designed the building at the height of the 1920s fashion for Tudor revival.

In 1922, the builders had been given a lump sum of £198,000 to construct it, which they did from the timbers of two ancient ‘three-decker’ battle ships. Records show more than 24,000 cubic feet of ships timbers were used including their decks now being the shop flooring: The HMS Impregnable – built from 3040 100-year-old oaks from the New Forest – and the HMS Hindustan, which measured the length and height of the famous Liberty building.

The ships were not Liberty’s only association with warfare. Carved memorials line the department store’s old staircase pay tribute to the Liberty staff who lost their lives fighting in WWII for a different kind of liberty – freedom from the regimes of the Axis powers.

One only need to look up to the roof , upon which stands a marvel of a gilded copper weathervane. Standing four feet tall and weighing 112 pounds, this golden ship recreates The Mayflower, the English vessel famous in American history for taking pilgrims to the new world in 1620.

The interior of the shop was designed around three light wells that form the main focus es of the building. Each of these wells was surrounded by smaller rooms to create a cosy feeling. Many of the rooms had fireplaces and some of them still exist.

Liberty of London was designed to feel like a home, with each atrium was surrounded by smaller rooms, complete with fireplaces and furnishings.

Ever the purveyor of craftsmanship, Arthur Liberty had a furniture workshop in Archway, London. Run by Lawrence Turner, the workshop produced Liberty Arts and Crafts furniture and the intricately carved panels and pillars found throughout the store. The craftsmen allowed his fantasy, ensuring every ornament was a one-off – paving the way for discovery.

Sadly, Arthur died seven years before the building’s completion and so never saw his dream realised. But, his statue stands proudly at our Flower Shop entrance to welcome you warmly into his emporium of wonder.

The architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner was very critical of the building’s architecture, saying: “The scale is wrong, the symmetry is wrong. The proximity to a classical façade put up by the same firm at the same time is wrong, and the goings-on of a store behind such a façade (and below those twisted Tudor chimneys) are wrongest of all”.

During the 1950s, the store continued its tradition for fashionable and eclectic design. All departments in the shop had a collection of both contemporary and traditional designs. New designers were promoted and often included those still representing the Liberty tradition for handcrafted work.

In 1955, Liberty began opening several regional stores in other UK cities; the first of these was in Manchester. Subsequent shops opened in Bath, Brighton, Chester, York, Exeter and Norwich.

During the 1960s, extravagant and Eastern influences once again became fashionable, as well as the Art Deco style, and Liberty adapted its furnishing designs from its archive.

LIBERTY PRINT ‘CONSTANTIA,’ 1961

In 1996, Liberty announced the closure of all of its department stores outside London, and instead focused on small shops at airports.

Since 1988, Liberty has had a subsidiary in Japan which sells Liberty-branded products in major Japanese shops. It also sells Liberty fabrics to international and local fashion stores with bases in Japan.

Liberty’s London store was sold for £41.5 million and then leased back by the firm in 2009, to pay off debts ahead of a sale. Subsequently, in 2010, Liberty was taken over by private equity firm BlueGem Capital in a deal worth £32 million.

In 2013, Liberty was the focus of a three-part hour-long episode TV documentary series titled Liberty of London, airing on Channel 4. The documentary follows Ed Burstell (Managing Director) and the department’s retail team in the busy lead up to Christmas 2013.

Channel 4 further commissioned a second series of the documentary on 28 October 2014. This series featured four, one hour-long episodes based on six months worth of unprecedented footage. Series two aired in 2014.

Liberty has a history of collaborative projects – from William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti in the nineteenth century to Yves Saint Laurent and Dame Vivienne Westwood in the twentieth.

Recent collaborations include brands such as Scott Henshall, Nike, Dr. Martens, Hello Kitty, Barbour, House of Hackney, Vans, Onia, Manolo Blahnik, Uniqlo, Superga, Drew Pritchard of Salvage Hunters and antique lighting specialist Fritz Fryer.

The website for Liberty also has these suggestions for you to watch for as you sally throughout the sprawling store:

The clock on the Kingly Street entrance of the Liberty store has some words of wisdom for the shoppers who pass by. It says “No minute gone comes back again, take heed and see ye do nothing in vain.” Above the clock, the striking of the hour chime brings out figures of St. George and the Dragon, to recreate their legendary battle every sixty minutes. On each corner of the clock are the angels of the Four Winds: Uriel (south), Michael (east), Raphael (west), and Gabriel (north).

Are you a fan of the tv show, The Great British Bake-off? I am! I learned so much about baking in general and about British desserts in particular from watching that show.

Yesterday I was in the cantina of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, and was delighted to see Lemon Drizzle Cake, Bakewell tart, and other desserts I learned about on the show.

I tried the Bakewell tart, and it was tasty. It needed some salt to balance all the sugar. But, that’s just me.

If you are a regular reader of my blog, you know that I rarely post images of the decorative arts. I am typically not a fan of fussy porcelains or fine cabinetry. I just don’t seem to have the gene that lets me appreciate that stuff.

But, today in London, I visited the Wallace Collection and it knocked my socks off. I mean, this place is crazy! The former mansion of the Wallace family was gifted to the country of Britain in the last years of the 19th century, and is still set up in a similar manner to the way in which the family lived.

As you might know, I’ve been to a few museums and house museums in my day, but this place is more opulent than any other.

All I can say is WOW! And then show you some (a lot, probably too many) pictures of this amazing place.

Oh, and p.s….Manolo Blanik shoes were also on display. I’ve never owned a pair and never will. But, to see the shoes interspersed with the collections added an element I’d not thought of before. My guide at the Wallace Collection told me that Blanik was an Anglophile and was particularly interested in the Wallace Collection. This is a new point of approach for me, and I could dig it!

Let’s go!

The first thing I heard in the excellent tour I joined, is that when this Japanese chest (and its matching partner) arrived in Europe, it absolutely blew the minds of connoisseurs. They were obsessed with the black lacquer and wanted to emulate it. They couldn’t, it turned out, because the plant that produces the lacquer did’t grow in the west.

Here’s my guide, standing in front of the Japanese chest.

That didn’t daunt them. The king of France set up a artisanal workshop, patronizing the best of the artistic producers known to France, and they experimented and experimented, trying to produce–if not lacquer itself–at least something that looked very close to it.

Above, King Louis XV, the king who developed the French fine arts.

This is the time period in which France is lifted by the decorative arts. France would no longer import fine luxury goods–they would produce them. It started then and is still going strong today.

The wardrobe below was produced in this workshop.

Before having a gander at the million photos I took today, introduce yourself to the Wallace Collection here with the director:

Now, please join me as I wander through the collection:

Can you say “opulence?”

Also, the Wallace Collection has a lovely restaurant!

And then, on to the armor!

And to a Gothic crown. Because, why not?

Check out the line of matching armor head pieces and shields.

Below: a portrait of Madame de Pompadour, commissioned by herself. My guide told the fascinating story of this woman and her involvement with the French king, and discussed the fascinating iconography of this portrait. Please note her tiny shoe peeking out from under her “Pompadour pink” gown, for which she set the fashion of the day. This is the type of detail by which Blanik was inspired. Looking at his shoes today, I could see it.

And, then there is this Jean-Honoré Fragonard masterwork: The Swing (1767).

You must be logged in to post a comment.