Italian Renaissance art

Villa Demidoff and Giambologna’s Il Gigante

As I sit in Denver on a very cold February morning, my mind wanders back to Tuscany and warm weather. I’m almost always behind in my posts and so I take this moment to post about Villa Demidoff.

In 1568, Francesco I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, purchased a great estate in the hills outside of Florence and commissioned the famous architect, Buontalenti, to build a splendid villa as a residence for Bianca Cappello. Bianca was the Grand Duke’s Venetian mistress. The villa was built between 1569 and 1581, set inside a forest of fir trees.

While very little of Buontalenti’s villa survives, at least we still have this fabulous and very large statue of Il Gigante, set facing a pond filled with water lilies.

The lilies are absolutely gorgeous in late August. I had never seen anything as magnificent as the first time I saw this lake of waterlilies in bloom! And, the statue ain’t bad either.

OK, ripping my eyes away from the pink flowers, I walked around towards the back of the statue:

Giambologna was the creator of this amazing sculpture:

Il Gigante, also known as “the Colossus of the Apennines,” is an astounding work of art. Giambologna designed the lower part as a hexagon-shaped cave from which one can access, through a ladder, to the compartment in the upper part of the body and into the head. The cavity is filled with light that enters from the eye holes in the head.

The exterior of the statue is covered with sponges and limestone pieces, over which water pours into the pool below.

We know that originally, behind the statue, there was the large labyrinth made from laurel bushes. At the front of the giant was a large lawn, adorned with 26 ancient sculptures at the sides.

Later, many of the antique statues were transferred to the Boboli Gardens, and the park became a hunting reserve. As a part of the Pratolino estate, it was abandoned until 1819, when the Grand Duke Ferdinando III of Lorena changed the splendid Italian garden in the English garden, by the Bohemian engineer Joseph Fritsch. The part was increased from 20 to 78 hectares.

The park, which had been owned by Leopoldo II since 1837, was sold upon his death to Paul Demidoff, who redeveloped the property. Demidoff’s last descendant bequeathed the property to Florence’s provincial authorities.

And I feel better already. I can feel my cold, clenched muscles relax under the spell of the Tuscan sunshine. Soon I will be there again.

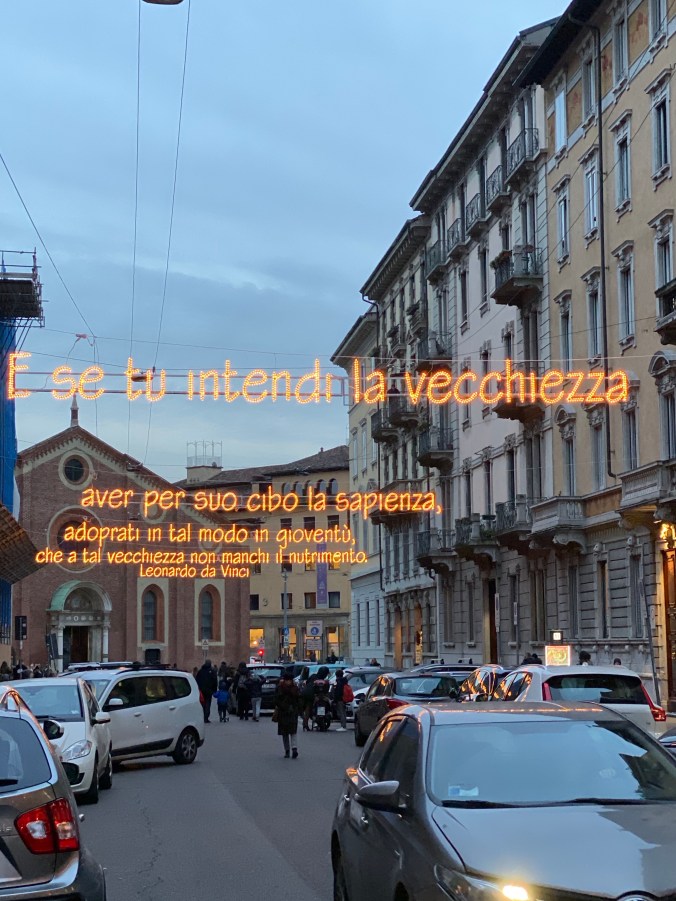

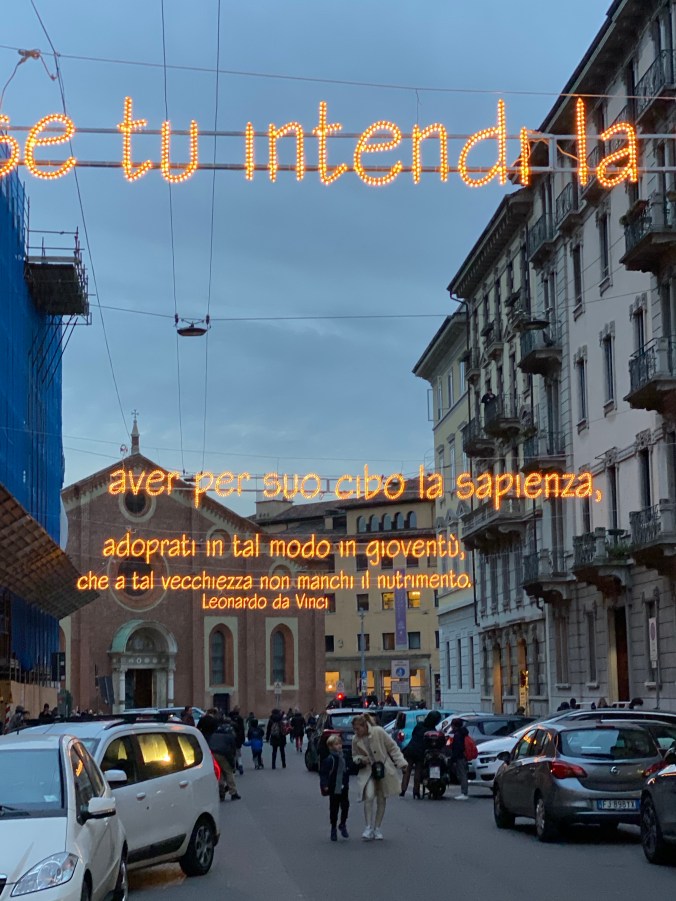

Leonardo’s advice on aging

Today is my birthday (and Michelle Obama’s!) and, as I mark how fast the years go by, it seems like the right time to mention these cool street lights in Milan. They hang near the famous refectory where Leonardo da Vinci painted The Last Supper at Santa Maria delle Grazie. It is sage advice for us all:

Acquisita cosa nella tua gioventù che ristori il danno della tua vecchiezza e se tu intendi la vecchiezza aver per suo cibo la vecchiezza adoprati in tal modo in gioventù che a tal vecchiezza non manchi il nutrimento. Leonardo da Vinci

My poor translation goes something like this. I think it captures the intent if not the poetry:

Acquire in your youth that which will restore the damage of your old age. And if you intend old age to have wisdom, then you’ll need to acquire the nourishment in your youth. Leonardo da Vinci

The Mona Lisa in 3-d

Sforzesco Castle, Milan

Wow. Just wow. I don’t know why I never paid a visit to this astounding place before now!

And, last, but certainly not least, you don’t see a lot of elephants in Italian art, but here is a big exception to the rule.

The Poldi Pezzoli Museum, Milan

Yikes! Nothing like being met by an army! The outstanding collection of armor below is just one of the many parts of the Poldi Pezzoli Museum that will amaze you in Milan.

The Poldi Pezzoli Museum is housed in the original 19th-century mansion built by Milanese aristocrat, Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli (1822-1879). His parents and grandparents had already begun the family’s art collection and he built his palazzo in this tony section of Milan to house the collection it as he continued to enlarge it. When he died, he left his collection and house to the Brera Academy. The Poldi Pezzoli Museum was opened to the public in 1881 on the occasion of the National Exposition in Milan and has since become an archetype for other famous collectors.

The Poldi Pezzoli is one of the most important and famous house-museums in the world. Located near the landmark Teatro La Scala and the world-renowned fashion district, this house-museum is beloved by the Milanese and international public.

The Poldi Pezzoli is a member of the Circuit of Historic House Museums of Milan, a city network established in 2008 with the aim of promoting the Milanese cultural and artistic heritage.

During World War II, the museum was severely damaged and many paintings were completely destroyed. The palazzo itself was rebuilt and in 1951 it was reopened to the public.

Not all of the house was restored as it appeared during Poldi Pezzoli’s life, but it was instead fitted out as a museum. The grand entryway, with its fountain filled with koi and its spiral staircase are original, as are at least 2 of the piano nobile galleries. You’ll recognize them right away in the pictures below.

The outstanding collection includes objects from the medieval period to the 19th century, with the famous armor, Old Master paintings, sculptures, carpets, lace and embroidery, jewels, porcelain, glass, furniture, sundials and clocks: over 5000 extraordinary pieces.

Let’s begin at the entry way. What a greeting!

Below: the view of the fountain from atop the staircase:

I was a bit obsessed by the fountain; can you tell?

Allora, moving on:

Angels in the architecture:

Dragons on the pottery:

I love the way they display the ceramics: why not affix objets to the ceiling? It is a wasted flat space otherwise. Genius.

Moving on to the important objets: Piero del Pollaiuolo magnificent Portrait of a Young Lady.

Botticelli’s The Dead Christ Mourned:

Bellini:

Ah, the glass. It gets me every time:

The panel below made me laugh. I love how the sculptor included the slippers at the side of the bed! In this dastardly scene of homicide, don’t forget the slippers!

Since 2019 marks the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death, the world is paying homage to the great artist with myriad exhibitions. The Poldi Pezzoli joins them with a major painting, on loan from the Russian Hermitage Museum, just for the occasion. Leonardo painted this work during his time living in Milan.

Palazzo di Brera, Milano

Milano’s beautiful Palazzo di Brera was created along with the Accademia di Belle Arti in 1776 to serve the students studying at the University.

The Jesuits built the Baroque palace at the end of the 17th century as a convent (the word convent is used for monasteries in Italy). After they were unceremoniously expelled, the Palazzo Brera was remodeled in the neoclassical style.

Napoleon took control of Italy and declared Milan the capital. He filled the Brera with works from across the territory. As a result, it is one of the few museums in Italy that wasn’t formed from private collections, but rather by the Italian state.

When the Palazzo di Brera was taken away from the Jesuits by Queen Maria Teresa of Austria, it was meant to become one of the most advanced cultural institutions in Milan. It still lives up to that status today. Besides the Academy and the beautiful Art Gallery, the palazzo holds the Lombard Institute of Science and Literature, the Braidense National Library, the Astronomical Observatory and a Botanical Garden maintained since he 1700s.

Inside the cortile, Canova’s heroic statue of Napoleon:

The entrance to the palazzo:

There is a garden at the back of the palazzo. The fortified walls and turrets of the building complex seen back here are massive and medieval, and very unlike the sophisticated facade of the palazzo. This Orto Botanico comprises a tiny corner of the hectic city has aromatic herbs, wildflowers and a small vegetable garden for research.

The Palazzo di Brera started life as a Jesuit college built on green land just outside the old city walls and its name reflects the location. In fact, the district, palace, and gallery all take their names directly from their locale as the Medieval dialect. The word “brayda” means “grassy clearing”. The word slowly evolved into “brera” or “bra;” it is also the root word of Vernona’s Piazza Bra.

Inside the Palazzo di Brera resides the beautiful Biblioteca Braidense:

More about Canova’s statue of Napoleon:

The plaster model for the bronze statue:

What caught my eye at the Brera? These works:

Andrea Solario, Madonna of the Carnations:

I loved Carlo Crivelli’s amazing panel paintings, which are actually somewhat 3-d. I’ve not seen that before in paintings of these kinds:

Another luscious work by Carlo Crivelli: Madonna and Child.

Some of the altarpieces in the Brera collection are sumptuously beautiful; breathtaking, actually.

This random lion caught my eye and I don’t even remember from what painting! I was a bit agog at the Brera. I started feeling the Stendhal syndrome, big time.

Raphael:

Piero della Francesca:

A ubiquitous scene, all over Europe:

Florence’s Duomo: better late than never

For my last birthday, I climbed the 1,000,000 steps to the top of Florence’s cathedral with a friend who shares a January birthday. Even though we live in a world where the word “awesome” is overused to the point of oblivion, I can only describe the duomo experience as awesome.

Unfortunately, I have been negligent in getting my pix and videos posted! I’m trying to catch up! I’m only about a year (11.5 months to be exact) late. Oh well…I’ll try to do better in the future.

First, let me share this Youtube video with you, because it captures how I felt!!

Before ending this very long post, I want to add a photo I came across of a 1940s visitor at the top of the dome

Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence

Spend a little time in Florence, Italy, and you will soon discover that the work of fine arts restoration is very much alive and well in this magnificent city. It just makes sense.

What you may not realize, is that one of the famous artistic workshops of the Italian Renaissance, the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, established in 1588 at the behest of Ferdinando I de’ Medici, is still functioning today. Ferdinando sponsored the formation of this workshop to provide the elaborate, inlaid precious and semi-precious stoneworks that he so admired. And you can visit the premises.

And, what is this art of inlay? If you’ve been to Florence, chances are good that you’ve visited the Chapel of Medici Princes in San Lorenzo. That magnificent, opulent chapel is an example of the art of stone inlay at its most excessive.

The overall decoration of the Cappella dei Principi (Chapel of Princes) in the Basilica di San Lorenzo di Firenze takes the art form to a whole new level. The technique, which originated from Byzantine inlay work, was perfected by the Opificio masters under the Medici patronage and the artworks they produced became known as opera di commessi medicei (commesso is the old name of the technique, akin to the ancient craft of inlay) and later as commesso in pietre dure (semi-precious stones inlay).

The artisans performed the exceptionally skilled and delicate task of inlaying thin veneers of semi-precious stones, especially selected for their color, opacity, brilliance and grain, to create elaborate decorative and pictorial effects. Items of extraordinary refinement were created in this way, from furnishings to all manner of artworks. Today, artisans trained at the Opificio assist many of the world’s museums in their restoration programs.

I recently was introduced to a fantastic workshop in Florence, the Lastrucci. It was there that my interest in this typically Florentine art form originated.

The Opificio workshops were originally located in the Casino Mediceo, then in the Uffizi and were finally moved to their present location in Via Alfani in 1796, or you know, slightly after the formation of the United States of America. At the end of the 19th century, the institute’s activities moved away from the production of works of art and towards the art of restoration. At first specialising in hardstone carving, in which the workshops were and are a world authority, and then later expanding into other related fields (stone and marble sculptures, bronzes, ceramics).

The Opificio delle pietre dure, which literally means “Workshop of semi-precious stones,” is a public institute of the Italian Ministry for Cultural Heritage based in Florence. It is a global leader in the field of art restoration and provides teaching as one of two Italian state conservation schools (the other being the Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione ed il Restauro). The institute maintains also a specialist library and archive of conservation, as well as a very fine, small museum displaying historic examples of pietre dure inlaid art and artifacts. A scientific laboratory conducts research and diagnostics and provides a preventive conservation service.

The frescoed halls within the museum are lovely in their own right:

But one comes here, after all, to see the stone work:

The museum displays extraordinary examples of pietre dure works, including cabinets, table tops and plates, showing an immense repertoire of decoration, usually either flowers, fruits and animals, but also sometimes other picturesque scenes, including a famous view of the Piazza della Signoria.

There is also a large baroque fireplace entirely covered in malachite, a dazzling and brilliant green stone as well as copies of painting executed in inlaid stone. Some of the exhibition space is dedicated to particular types of stone, such as the paesina, extracted near Florence, the grain and color of which can be used to create vivid landscapes.

There are vases and furnishings decorated with Art Nouveau designs of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including a tabletop with a harp and garland by Emilio Zocchi (1849) and another decorated with flowers and birds by Niccolò Betti (1855).

While one is not able to visit the restoration workshops, a visit to the small museum is a must for understanding the fine art of semi precious stone inlay, which is itself a very Florentine tradition.

Here are some examples of pietre dure that caught my eye in the museum.

Climbing to the museum’s 2nd floor, you know you are in a place that values stone when you see the back of each step: each step got its own stone type. Extraordinary.

An exhibition of the technical processes of pietre dure works through history is found on the upper floor.

For me, the upper floor was the most interesting. While I admire the workmanship and skill that goes into these incredible inlaid pieces, usually the artwork itself doesn’t move me. But the upper floor has amazing didactic information, original casework furniture specifically designed for the artisans, and tools. There is also a very informative film that tells the story very well.

Below, a few of the dental type tools used in the craft. Dazzling.

Casa Martelli, Florence, part 1

Last month, I finally visited the Palazzo Martelli, which I’ve walked by for several years, always hoping to enter. It’s only open a few days of the week and only by guided tour, but it is so worth the visit! I highly recommend!

For centuries–right up to the 1980s– the the Palazzo Martelli was the residence of one of Florence’s oldest noble families. A visit to this jewel of a museum takes the visitor into a suite of opulent period interiors, including the ground-floor stanze paese (landscape rooms), whose walls and ceilings are painted with trompe-l’œil scenes; an elegant grand staircase leading to the piano nobile; the spaces of the main floor, which include a chapel, a ballroom, fascinating picture galleries, and a great hall and other richly-decorated rooms.

Palazzo Martelli underwent a series of renovations in the early 18th century, under the care of Niccolò Martelli and his son Giuseppe Maria, who was the archbishop of Florence. Although there had been Martelli family homes on this site from at least the 13th century, it was only in 1738 that the family’s residence was transformed into the palazzo we see today. It was designed by architect Bernardino Ciurini, and decorated by the painters Vincenzo Meucci, Bernardo Minozzi and Niccolò Contestabile, and the stuccatore (stucco artisan) Giovan Martino Portogalli. The exterior, as shown above, presents a sober, austere image to the outside world, with only the balcony to soften the hard edges. This hard exterior is the way Florentines presented themselves to the outer world. But, oh, what lies inside is quite the opposite!

Today, Casa Martelli houses the last Florentine example, in public hands, of a well-known art collection formed largely during the 17th and 18th centuries. A visit proceeds through the rooms of the ground floor and the piano nobile, updated according to the tastes of the period, where visitors can enjoy the picture gallery—rich with masterpieces such as Piero di Cosimo’s Adorazione del Bambino, two wedding panels (pannelli nuziali) by Beccafumi, and magnificent paintings by Luca Giordano and Salvator Rosa—as well as the antique furniture, tapestries, and various decorations and objects dispersed throughout the home.

Casa Martelli remained in the Martelli family’s possession until the death of Francesca Martelli in 1986. For a brief period, the residence passed into the hands of the Florentine Curia, to whom Francesca had bequeathed the palazzo in her will, before eventually becoming property of the Italian State.

Two of the most outstanding art works that the Martelli family possessed have now been removed from the palazzo and are in the Bargello and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Both are attributed to Donatello. The monumental coat-of-arms that Donatello created for Roberto Martelli is now in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello collection. Today a copy hangs in the place of honor. You see it below, on the far wall with a red background.

Likewise, a statue of David also attributed to Donatello (see below) once stood in this hall; today the statue is in Washington, D.C.

Currently the museum is only open to visits a couple of days of the week, and then only with a guided tour. If you get the chance, you should definitely visit the casa, or palazzo. It is wonderful.

But, if you can’t wait or can’t get to Florence, you can fortunately take a virtual tour of the museum here: http://www.polomuseale.firenze.it/musei/visita/casamartelli/tour.html

Even accounting for the loss and dispersal of items, the collection remains impressive, including works by Piero di Cosimo, Francesco Francia, Francesco Morandini, Salvator Rosa, Giordano, Beccafumi, Sustermans, Michael Sweerts, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Orazio Borgianni, Francesco Curradi, and collections of small bronzes, including some by Soldani Benzi. The works are displayed in the crowded arrangement typical of the period.

When you visit the casa today, you enter through large wooden doors and an iron gate, both dating to 1799. Inside the building, at the far end of a short interior courtyard, is a mural painting with an illusory effect, done in 1802 by Gaspero Bargioni.

One enters a door to the grand staircase from this cortile:

The original ironwood of this staircase is fabulous!

Where you see the neoclassical sculpture of Psyche, imagine a statue of David by Donatello standing there. That’s the work of art the Martelli family displayed in this place of honor. The Donatello statue is today in Washington, D.C.

Below is the copy of the Donatello coat of arts made for the Martelli family. The original is in the Bargello.

Entering the first gallery off the entrance, you begin to enjoy the art collections for which the Martelli family was renowned, including the many outstanding ceiling frescoes they commissioned over the centuries for this opulent family home.

In the painting below, we catch a glimpse of members of the Martelli family in the 17th century. A servant offers them a tray bearing cups of the hot chocolate which were a la mode at the time. Oh, to have been a fly on the wall!

Many of the doors throughout these galleries are embellished with these gilt decorations, every door with a different combination of items:

The artist signed his name on the ceiling mural, as you can see below:

I was interested in these little pops of passamaneria (trimmings) found covering the nailheads that these paintings are hung on. I’m a huge fan of all things passamaneria, and I’ve never seen anything like these before. I love it when I experience something completely new!

Now we enter the 2nd gallery, with its own wonderful ceiling mural. I was enchanted by these 2 little boys in the mural. They are busily talking pageboys, holding the lady’s train. What were they discussing, I need to know!

The door knobs in some of these galleries were fabulous! Butterflies!

The inlaid commesso fiorentino furniture was outstanding as well:

Next we enter the 3rd gallery, with a ceiling fresco treating the subject of Donatello as sculptor to the Martelli family. The connection was real and it is very entertaining to see its history play out on the ceiling!

That’s Donatello in the yellow smock:

Oops, another shot of my latest obsession.

Below: my other obsession.

Also notable in this room are the very old and very elegant draperies, also with very elegant trim or passamaneria.

And, of course, this family would own some fine Manifattura Richard Ginori ceramics:

The next gallery, with another fine frescoed ceiling:

In this room, I love the way the 2 drapery rods meet in the middle in a laurel wreath. The message is clear, the Martelli family was crowned with laurel:

That, of course, is Dante in the red, accompanied by Petrarch and Boccacio. Naturally they are crowned with laurel wreaths and the putto is sailing in with an extra, just in case:

In the next room, a private chapel was built for the last Martelli owner of the home. It is really quite something in terms of casework.

I don’t remember ever seeing a painting of a swaddled Christchild before. Another something new.

I’ve still got more to show you, but this post is already too long. I’ll finish it tomorrow…stay tuned!

You must be logged in to post a comment.